When the first Dáil met in 1919, there had been no Parliament in Ireland for over 100 years. One of the first questions was where the Dáil should sit.

A Parliament seeking a home

The revolutionary first Dáil had hired the Round Room of Dublin’s Mansion House for its first meeting on 21 January 1919. Thereafter, the Dáil met in the Mansion house and various other locations. After the Treaty with Britain and the general election of June 1922, the Oireachtas was in a position to take up a more permanent residence and set about finding a suitable building.

A postcard anticipating the day when the King and Queen of England would open a new Irish Parliament / Image courtesy of the Linen Hall Library

The building that had housed the Irish Parliament before it was incorporated into the British Parliament in 1801 might have seemed the obvious choice. Irish nationalism since 1801 had centred on an Irish parliament once again meeting in Parliament House. In 1911, when King George V and Queen Mary visited Ireland, Dubliners could buy postcards optimistically depicting the King arriving to reopen the Irish Parliament. The British Government had acknowledged this relationship with Parliament House in the Government of Ireland Act 1920.

If the Government of Southern Ireland signify their desire to acquire for the use of the Parliament of Southern Ireland the premises (hereinafter referred to as "the bank premises") of the Bank of Ireland situate in or near College Green, in the City of Dublin, they shall be entitled to do so.

However, Parliament House was owned and occupied by the Bank of Ireland, and there was another more important objection. The building opened almost directly onto the street, and could be vulnerable to attack. Disagreement over the Treaty had escalated from political debate to Civil War. Dublin was in turmoil, with battles in the streets and buildings destroyed. The new parliament house would have to be able to withstand potential attack from the anti-Treaty forces.

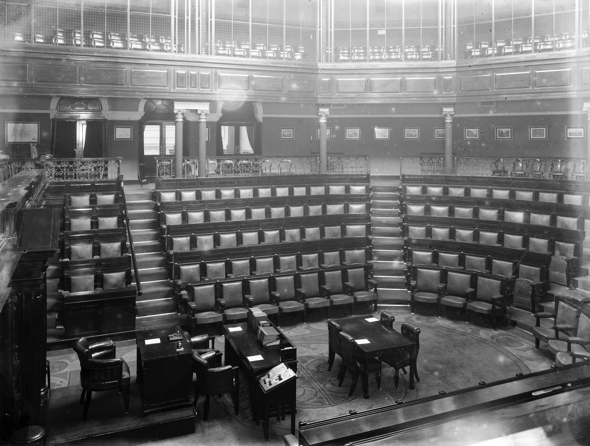

When Michael Collins viewed Leinster House, he was convinced it was the only premises that could house the new Oireachtas. Not only was it set back from the street, it also had the finest lecture theatre in the country, with seating for 700 people. With minimal alteration, the lecture theatre could accommodate the Dáil. Collins leased it from the owners, the Royal Dublin Society, RDS, for eight months, and this is where the Third Dáil convened on 9 September 1922. Collins himself never took his seat in Leinster House, having been assassinated the month before the Dáil met.

Leinster House / Image courtesy of the National Library of Ireland

The lecture theatre had many disadvantages, from the tip-up seats to the fact that Dr. John Joly’s radium lab, where he had developed the “Dublin method” of cancer treatment, remained in place behind it. The Seanad’s temporary home was even less satisfactory. The Upper House was put up in the antique furniture room of the museum adjoining Leinster House, a situation deemed unworthy of it.

We have put up for over one and a half years with a condition of grave discomfort … Your Chairman and your official staff have sat here upon a scaffold, behind which there is a cupboard, from which your Chairman emerges, and into which he disappears.

Leinster House only ever been intended to be a stop-gap, and the question of a more suitable location was soon on the table. The old Parliament House was again suggested, but the Bank of Ireland would have to be rehoused at the Government’s expense, which would have been extravagantly costly as well as time consuming.

The RDS lecture theatre was altered to accommodate the Dáil / Image courtesy of the National Library of Ireland

Dublin Castle was favoured by the Seanad, but it was in use as a temporary court house following the destruction of the Four Courts in the Civil War. The Royal Hospital in Kilmainham was also suggested, as was a move out of the “foreign town” of Dublin.

From my knowledge of the past, Kilmainham was a very easy place to get into, but a very difficult place to get out of… If we went to Kilmainham even to occupy it as temporary premises and spent £45,000 there… it would not be so easy in the future to remove from there to the place that we all hope, and that every Irishman throughout the world has hoped, we will one day occupy — our old Parliament in College Green.

Even after the Free State bought Leinster House from the RDS in 1924, discussions on moving the Oireachtas continued. In the 1930s the idea of creating a parliamentary quarter was explored. Plans envisaged a cathedral and a concert hall as part of it, representing religion and culture. Against a background of the new State’s precarious financial situation these ideas came to nothing, and the Oireachtas remains in Leinster House today.

Leinster House

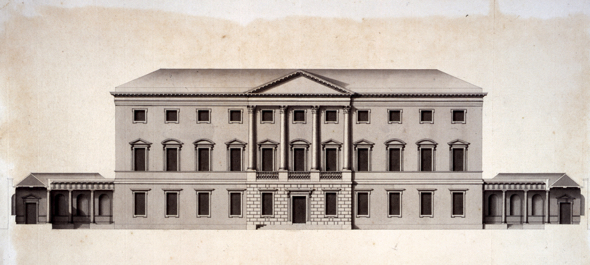

Leinster House was built in the mid 18th century by the Earl of Kildare, James Fitzgerald. Just 22 years old when he inherited his father’s title, Lord Fitzgerald immediately bought a piece of land in Dublin where he planned to build a splendid town house that would reflect his wealth and social status. When a friend remarked that that site was remote and unfashionable, the Earl is said to have replied, “They will follow me wherever I go.”

Fitzgerald hired Richard Castle, the leading architect in Ireland, to create a Palladian country house in town with a double height hall and a picture gallery. Castle’s design, in particular the projecting bow on the north side, is said to have inspired the design of the White House, the residence of the President of the United States. The architect of the White House, James Hoban, was an Irishman who studied in Dublin, and would certainly have been familiar with the design of Leinster House.

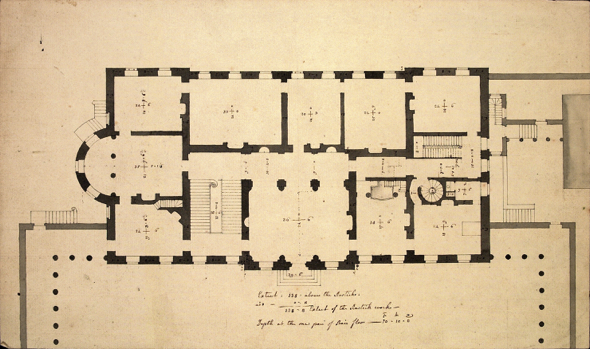

Ground floor plan of Leinster House by Richard Castle / Image courtesy of the Irish Architectural Archive

Construction started in 1745 and continued for several years. At the time, the sittings of the Parliament of Ireland drew a large social circle to Dublin each winter for the season. In 1747, the Earl married Lady Emily Lennox, daughter of the Duke of Richmond, but it was some years before they could take up residence in their town house. In 1766, the Earl was created Duke of Leinster, and his town house became known as Leinster House.

Design for the entrance front of Leinster House by Richard Castle / Image courtesy of the Irish Architectural Archive

After the Parliament of Ireland closed down in 1801, Irish MPs needed houses in London, not Dublin. As the annual season became less important, many influential families let their Dublin houses go. In 1815, the third Duke of Leinster sold Leinster House to the Dublin Society for £10,000 and a yearly rent of £600.

Since the union with England our family residence in town had been quite neglected and was now more like a convent than a nobleman’s hotel. A large bell at the gate (which had long been condemned to silence) now announced to the housekeeper the return of one of the Ancient inhabitants of Leinster house. She received us at the door & by the light of a solitary candle, we made our way to a once stately bed-chamber!

While the era of the aristocracy in Dublin was waning, the Dublin Society was at the forefront of a new era of egalitarianism. It aimed to foster and promote arts and science in a society in which more and more people had some level of education. Over time the society, which became the Royal Dublin Society when King George IV became patron, added extensions and annexes to the original house, providing space for a library, museums, science laboratories and a huge public lecture theatre.

Architect’s drawings for the Royal Dublin Society’s extensions to Leinster House / Image courtesy of the National Museum of Ireland

The Oireachtas took up residence in the RDS as a temporary solution, and Members were aware that their presence was interfering with public access to the society’s collections and facilities.

We are here in the first place as guests, and in the second place very much like squatters, because, I suppose, as time goes on our claim to remain here gets a little stronger. We are very much indebted to the Royal Dublin Society for their generosity, for their courtesy, their great help, the great assistance that they have, at all times, given us in making our stay here as comfortable as possible, and for their readiness in meeting us on almost every occasion that we have had to make representations to them for still more hospitality.

When the State bought Leinster House from the RDS in 1924, the society transferred its activities to Ballsbridge and the Oireachtas was able to begin adapting the House to its needs. The picture gallery, which had been a ballroom in the time of the Dukes of Leinster, was fitted out for the Seanad and the lecture theatre was altered to suit the needs of the Dáil.

Section model showing Leinster House 2000 as it connects with the Leinster House complex / Image courtesy of Donnelly Turpin Architects/Barry Mason

Today, Leinster House is at the centre of a complex of buildings that accommodate the Oireachtas Members and staff. Over the years, extensions and modifications have adapted the space to the changing needs of the Parliament. For example, the Leinster House 2000 building reflects the increasingly important role that committees play in the Oireachtas and the impetus to provide public access to Oireachtas business. Leinster House 2000 provides four purpose built meeting rooms with sound and video recording facilities to enable meetings to be broadcast.

Last updated: 7 October 2020