The Oireachtas Library & Research Service exhibits selected treasures from the Oireachtas collection in a display case in Leinster House. Check back for updates and information on these unique artefacts.

December 2022

This month, to mark the centenary of the Free State Constitution, the Oireachtas Library is displaying The Irish Constitution, Explained by Darrell Figgis, alongside other texts by Figgis.

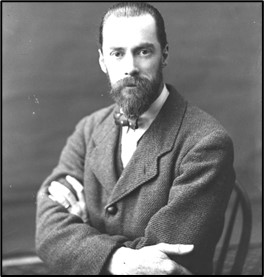

Darrell Figgis was a well-known literary figure with a keen intellect and his many published works include poetry, novels, plays, literary criticism, art criticism and journalism.

A member of the Irish Volunteers, Figgis participated in the plot to smuggle German rifles into Howth harbour via Erskine Childers’ sailing yacht, the Asgard. Figgis did not participate in the Easter Rising but was interned in several British prisons between 1916 and 1919. His experience in Reading Gaol is relayed in his memoir A Chronicle of Gaols.

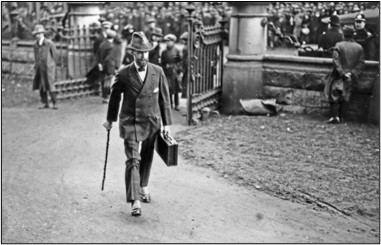

Darrell Figgis arriving for the Treaty debates in January 1922, a few months before he became chair of the Constitution committee. Photo: Independent News And Media/Getty Images)

A free democratic constitution: the 1922 Constitution committee

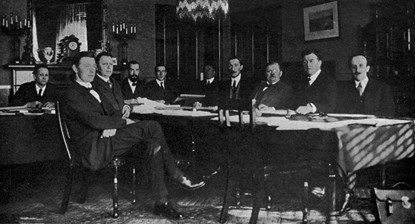

The first constitution of the Irish State came into being in 1922. Arthur Griffith appointed Figgis as acting chair of the Constitution committee, standing in for Michael Collins. The committee produced three self-contained constitutions for review by the Provisional Government. Figgis’s The Irish Constitution contains a draft and an explanation, including chapters on "What is a constitution?" and "The People as Law-Makers."

The draft texts were then subject to consultation by the Provisional Government and brought before the British Government for revision. An amended text was agreed, and published by the Provisional Government on 16 June 1922, the day of the 1922 General Election. This text formed part of Constitution of the Irish Free State (Saorstát Éireann) Act, 1922. The Constitution of the Irish Free State (Bunreacht Shaorstáit Éireann) was adopted by Act of Dáil Éireann sitting as a constituent assembly on 25 October 1922.

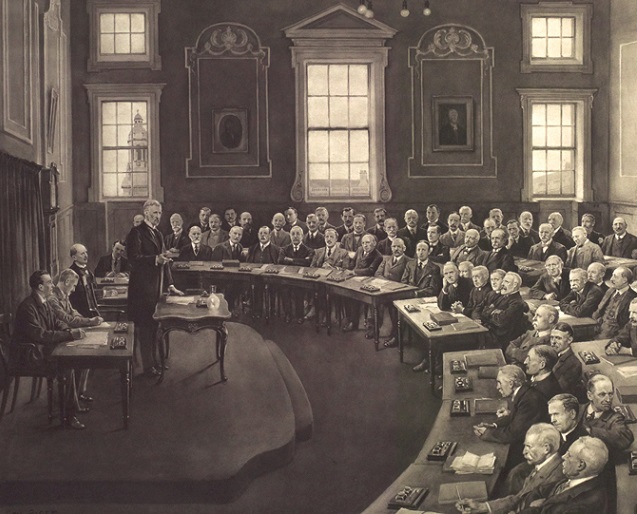

From left to right: R. J. P. Mortished (Secretary), John O’Byrne, B.L.; C. J. France, Darrell Figgis (Acting Chairman), E. M. Stephens, B.L. (Secretary); P. A. O’Toole, B.L. (Secretary); James MacNeill, Hugh Kennedy, K.C.; James Murnahan, B.L.; James Douglas. (Prof. Alfred O’Rahilly and Kevin O’Shiel, B.L. were absent from the Session). Photo courtesy of Project Gutenberg.

"Poor Darrell Figgis lost his nice red beard"

Figgis served as an Independent TD for Dublin County in the 3rd and 4th Dáil from 1922-1925. His pro-Treaty stance in 1922 put him at odds with the Sinn Féin party and the IRA. It resulted in an assault on Figgis at his home on Fitzwilliam Street, where he lived with his wife Millie, and where members of the IRA cut off his prized beard.

Almost 30 years later, Bob Briscoe, who later became Lord Mayor of Dublin, gave an account of the attack:

Figgis started making some very detrimental remarks about the IRA. We did not consider him a menace -- but he annoyed us with his waspish stings . . . some of us held him tipped back on his swivel chair while one man produced a glittering razor. Figgis squealed like a pig ... I think he would have been happier if we had just cut his throat.

His political career halted when he was forced to resign from the Dáil committee established to examine proposals to develop broadcasting in the state. It was alleged that he had business associations with the owner of a commercial company who had eyes on obtaining the contract.

Darrell Figgis died in 1925, aged 43. He is buried in West Hampstead Cemetery in London.

Related texts by Figgis in the Oireachtas digital library

A Short Plot: A Sidelight on Political Expediency

Further article

The Short and Tragic Life of an Irish Dandy (from Independent.ie)

References

The Irish Free State Constitution Act 1922 (Session 2) was an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom, passed in 1922 to enact in UK law the Constitution of the Irish Free State, and to ratify the 1921 Anglo-Irish Treaty.

The papers of the Constitution Committee are held by the National Archives of Ireland.

Dáil Éireann debate, Wednesday, 18 Oct 1922 – Constitution of Saorstát Eireann Bill.

Source: Masterofmalt, CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons

September 2022

'The oppressions and cruelties of Irish revenue officers'

This month the Oireachtas Library is displaying an 1818 pamphlet entitled Oppressions and cruelties of Irish revenue officers. Written by Reverend Edward Chichester, justice of the peace for Donegal, the somewhat paternalistic pamphlet contained accounts of harsh and unfair treatment of his parishioners by revenue officers, particularly in the barony of Inishowen.

According to the testimonies, officers were routinely soliciting bribes and falsely accusing people of illegal distilling.

The acting inspector-general of excise Aeneas Coffey took great offense at Chichester’s accusations, issuing his own pamphlet soon after. A distiller himself, Coffey defended the integrity of his officers and stated that the excise law was supported by the majority of the population. Chichester issued another pamphlet to counter Coffey’s response, again emphasising the impoverished situation of many of his parishioners, and the unfair application of the law by revenue officers.

Aenaes Coffey, distiller and inspector general of excise. Source: Masterofmalt, CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons

Just what was going on? As income tax would not be introduced in Ireland until the 1850s, revenue was reliant on indirect taxation such as excise and customs duties. Whiskey had been subject to excise duty since the mid-17th century, but tax collection in Ireland was extremely disorganised and began to come under increasing scrutiny from the late 18th century. Private distilling was very common and not subject to a licence as long as the amount produced was low, so it was a shock when the laws changed to enforce both the registration of a license (which meant paying the excise duty) and a minimum size for stills. It became almost impossible for small stills to procure licenses and hundreds of them subsequently moved underground.

In poorer rural areas such as Donegal, tenants often used the profits from distilling to pay their rents, whether through the sale of grain or the alcohol itself. Given the high level of illegal distilling it was sometimes in the financial interests of revenue officers to take bribes for looking the other way. To make matters worse, fines were often levied at an entire townland or parish, punishing the innocent along with the guilty. Where people were unable to pay, officers seized animals or furniture, and landlords themselves sometimes stepped in to cover the fines. This led to an unusual situation in Ireland where landlords and tenants found themselves united against the revenue office. This was particularly the case in Donegal, where an 1806 report estimated that one out of every two houses had its own still.

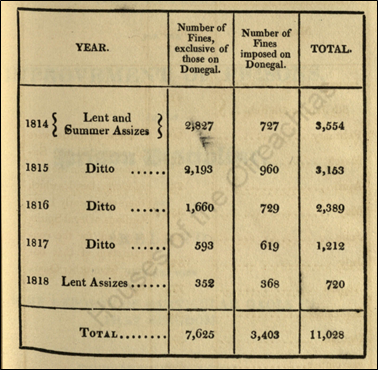

A return of the number of fines imposed on parishes and townlands between 1814 and 1818, with separate figures for Donegal

Tensions over the issue grew to the point where revenue officers who went ‘still-hunting’ could find themselves facing violent resistance. They insisted on armed escort from the military, but the soldiers generally disliked the duty, as they considered it too low a priority to warrant a risk to their lives (and they were consumers of the poitín themselves). Eventually a dedicated revenue police was formed and had some success in the townlands in which they were concentrated. But once they left an area, private stills were immediately reinstated, and illegal distilling would remain rife until the mid-1800s.

Provenance

These pamphlets are from the former ministerial Irish Office in London. A large pamphlet collection was transferred from London to the Oireachtas Library in the 1920s.

References

Dawson, N. (1977). Illicit distillation and the revenue police in Ireland in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Irish Jurist, vol. 12, no. 2, pp. 282-294.

Kanter, D. & Walsh, P. (2019). Taxation, politics, and protest in Ireland 1662-2016. Palgrave Macmillan.

Houses of the Oireachtas

July 2022

“We felt…that a Census ought to be a Social Survey, not a bare Enumeration”

This month, following the initial release of official population counts in the 2022 Census, the Oireachtas Library is displaying a report of the 1841 Census. The preliminary results of the 2022 Census show that the population of Ireland has reached 5,123,536, marking the highest level since before the Famine.

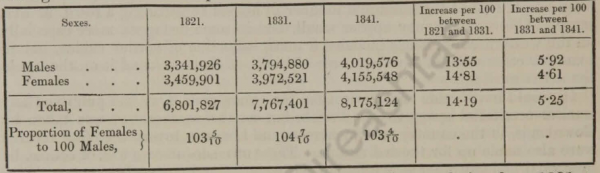

After rapid growth in the early 19th century the population had reached 8,175,124 in 1841 (with 6,528,799 in the counties that now form the Republic). There was a much more modest increase between 1831 and 1841 than between 1821 and 1831. Explanations for this included the exclusion of army staff stationed in the country, the high rate of emigration and the inconsistent standards applied in 1821 and 1831. Though the numbers have long been contested for these early 19th century counts, the 1841 Census did go further than previous ones to record more detail about Irish society, using a standardised form and being conducted over a shorter period of time.

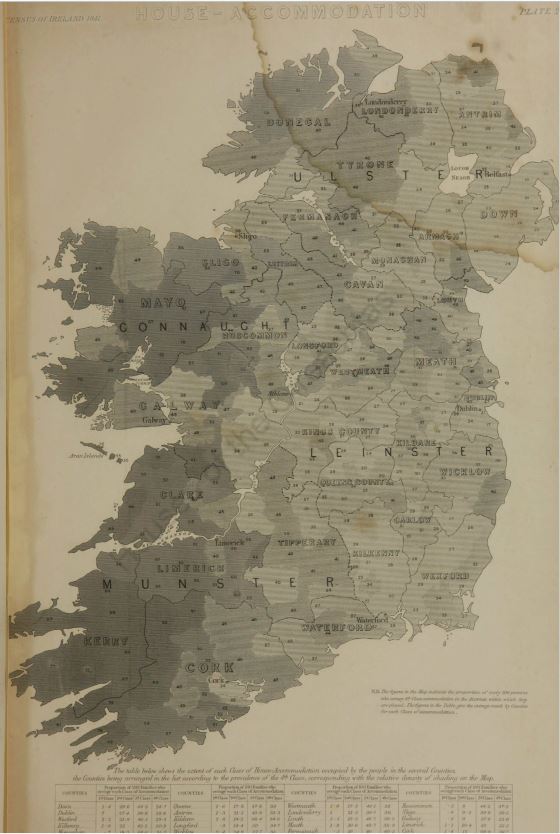

The Census recorded the number of dwellings in Ireland at 1,328,839, with 52,208, or 3.9%, uninhabited (The preliminary 2022 Census results show a vacancy rate of 7.8%). Dwellings were divided into four classes, the lowest, or fourth class, comprising mud cabins with just one room. 43.5% of rural families and 36.7% of urban families were living in the fourth class of accommodation, with nearly the same proportion again living in the third class. The map below shows the distribution of accommodation quality, with the darker shades indicating the lower classes. The extent of poor accommodation standards in Ireland was remarked upon in the final report.

The Census also recorded important information about education, trades and occupations, emigration, and livestock. There was even an estimate of tree coverage in the country.

The first full Census of Ireland was in 1821 and was conducted once a decade up to 1911. Reports like the one displayed here are particularly important as little remains of the original 19th century forms. The returns for the 1841 Census were destroyed along with those for 1821, 1831 and 1851 in the fire at the Records Office of Ireland in 1922. The returns for 1861 and 1871 were destroyed shortly after collection, and the returns for 1881 and 1891 were pulped for spare paper during World War I.

Provenance

This document is from the Dublin Castle Collection, the reference library of the former Chief Secretary’s Office at Dublin Castle. This was transferred to the Oireachtas Library in 1924.

References

Central Statistics Office. Census through History.

https://www.cso.ie/en/census/censusthroughhistory/

Moroney, Michael (2015). The 1841 Census – do the numbers add up? History Ireland [online], 23(3).

Houses of the Oireachtas

June 2022

This month, the Oireachtas Library is marking 100 years since the destruction of the Public Records Office of Ireland (PROI) with a display of an 1819 report by the Committee of Observation on the Public Records of Ireland.

“The history of a country is founded upon its archives.” Herbert Wood, Deputy Keeper of the Public Record Office of Ireland

A commission to investigate public record-keeping specifically in Ireland emerged from a wider British survey in the early years of the 19th century. Referring to “the state of disorder and confusion into which the records of the principal repositories of Ireland had fallen” the report outlined the poor physical conditions of repositories around the country, the messy arrangement of materials and lack of catalogues and indexes.

Despite the committee’s recommendations for improvements, it was not until 1867 that public record-keeping was centralised to a great extent in a dedicated Public Records Office in the Four Courts complex in Dublin. This complex was occupied by anti-Treaty IRA forces in April 1922.

On 28 June the Free State army began shelling the buildings, marking the first day of the Irish Civil War. On the morning of 30 June, an explosion of ammunition onsite caused a fire to spread rapidly, resulting in the devastating loss of administrative records dating back seven centuries.

This report is from the Dublin Castle Collection, the reference library of the former Chief Secretary’s Office, which has been in the Oireachtas Library’s possession since 1924. As this collection – much of which has been digitised - contains copies of some items once housed at the PROI, the library is sharing content with the Beyond 2022 project in Trinity College Dublin.

Beyond 2022 is gathering duplicate digital content from around the world to reconstruct the PROI as an open access virtual record treasury, which will be launched on 30 June 2022.

Provenance

These documents are from the Oireachtas Library’s Official Publications collection.

References

Wood, Herbert. “The Public Records of Ireland before and after 1922.” Transactions of the Royal Historical Society 13 (1930): 17–49.

Houses of the Oireachtas

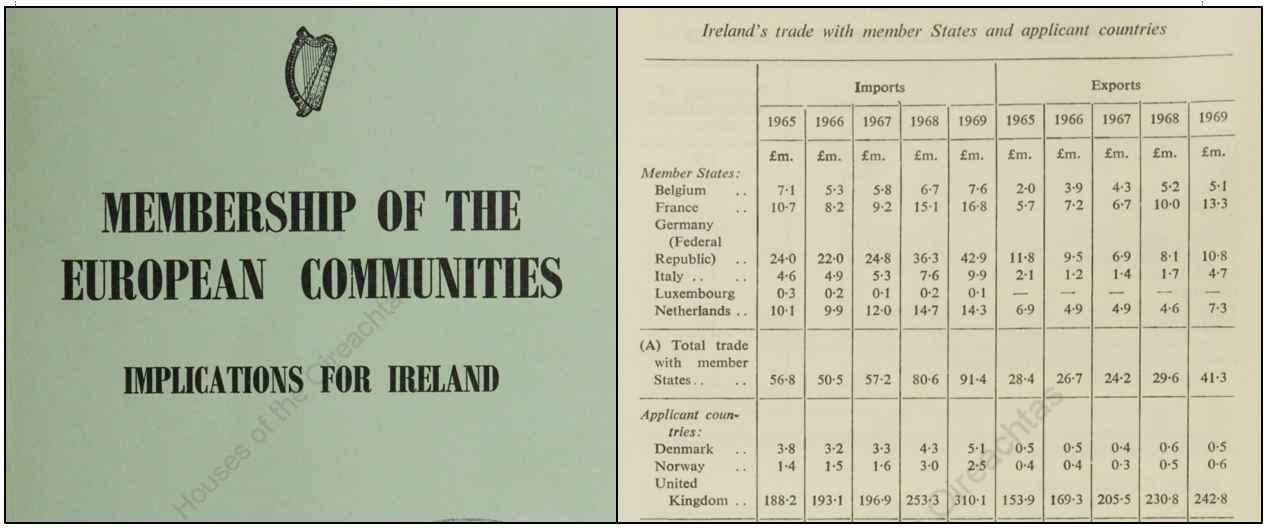

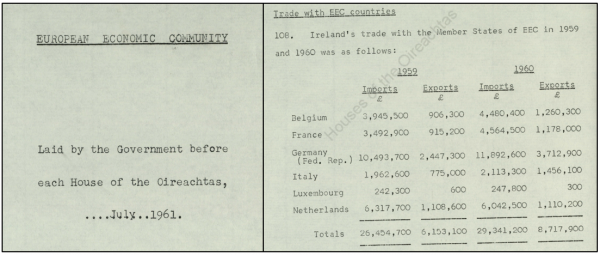

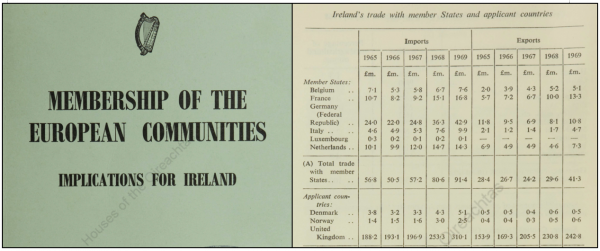

By the 1960s increased economic and political ties between Western European countries had formalised into three European Community organisations that would be a founding pillar of the European Union. The most prominent of these was the European Economic Community (EEC). At the same time Irish governments were taking a more active approach to opening and invigorating the long-stagnant Irish economy. The prospect of expanded trade and investment with a large swathe of continental Europe was an appealing one.

Ireland initially applied for membership of the EEC in 1961 along with the United Kingdom. The heavy dependence of Ireland on the UK market ensured that their membership applications remained intertwined throughout the process. As the 1961 White Paper noted:

“The attitude which has been adopted consistently by the Government to the question of Ireland's participation in the E.E.C. or a wider European grouping, is that primary regard must be had to our national interest and that while this would in certain circumstances, be served by our joining a grouping of which the United Kingdom was a member, it would not be served by joining the E.E.C, if the United Kingdom remained outside and we had to forgo our preferential advantages, in that market.”

The applications stalled in 1963 after objections to UK membership by Charles de Gaulle in France. They were reactivated in 1967, and after de Gaulle’s resignation in 1969, the path was clear to begin negotiations. The 1970 White Paper outlined the main implications of membership on issues such as agriculture, fisheries, taxation, free movement and equal pay. The report concluded that despite the challenges of the transition the national interest would be best served by entry to an enlarged EEC which included the UK.

Ireland signed the accession treaty on 22 January 1972. As the move required an amendment to the Constitution, a referendum was held in May, and was approved with over 83% of the vote.

For more on Ireland’s role in the European Communities/European Union, see this timeline prepared by the Oireachtas Library & Research Service.

Provenance

These documents are from the Oireachtas Library’s Official Publications collection.

References

O'Driscoll, M. (2013). Ireland through European Eyes: Western Europe, the EEC and Ireland, 1945-1973. Cork University Press.

Graham Horn. Source: Wikimedia Commons. License: CC BY-SA 2.0

April 2022

This month the Oireachtas Library is marking 50 years of Raidió na Gaeltachta with a display of RTÉ’s annual report from 1973. The report, covering the period of April 1972 to March 1973, outlines the inaugural year of programming at the new station, which broadcast for the first time on Easter Sunday, 1972.

Irish language programming was featured on Irish radio from the 1920s, and the concept of a dedicated station was suggested as early as 1926 by the Minister for Posts and Telegraphs J J Walsh. However, it was not until the late 1960s and after much campaigning by the Gaeltacht Civil Rights Movement and others that plans were finally made to establish a radio service for the Irish language community.

A headquarters was built in Casla, Co. Galway, with two further studios in Baile na nGall, Co. Kerry and Doirí Beaga, Co. Donegal. The station’s initial broadcasts were limited to the Gaeltacht regions but RTÉ’s annual report describes the ongoing technical work to extend the transmission throughout the country.

In terms of programming, magazine shows were running on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays from each of the three studios, with a focus on reconciling the different regions with different dialects. The report also mentions that the different dialects were less of a barrier than had been expected. The vast majority of content came from the Gaeltacht areas, with the noted exception of folk music. In addition to the magazine shows, the station broadcast dramas, regional current affairs and educational content.

Provenance

This document is from the Oireachtas Library’s Official Publications collection.

References

RTÉ. Local Radio Service for An Ghaeltacht, 1972. https://www.rte.ie/archives/2017/0228/856014-raidio-na-gaeltachta/

March 2022

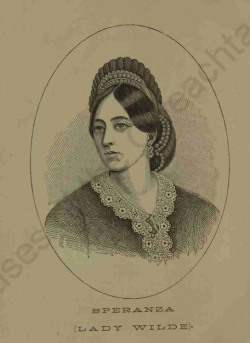

This month the Oireachtas Library is marking International Women’s Day by displaying an 1871 book of poems by Jane Wilde. Born in 1821, Lady Wilde was a polyglot, essayist, poet, Irish nationalist and advocate for women’s rights.

“Fainting forms, hunger-stricken, what see you in the offing? Stately ships to bear our food away, amid the stranger’s scoffing”

She began writing poetry in her 20s for the Nation newspaper, under the pen name Speranza, the Italian for hope. One of her most famous poems was the 1847 ‘The Famine Year’ (first published as The Stricken Land’), a scathing rebuke of the British government’s failure to prevent famine in Ireland following widespread potato blight.

In addition to political causes Wilde was very interested in folklore and myths, contributing to the Celtic cultural revival of the late 19th century. She held literary ‘salons’ at her homes in Dublin and London. She was also very close to her famous son, Oscar, and a significant influence on him.

Though she supplemented her income through writing, Wilde fell into poverty in her later years trying to support herself and her other son William. She was denied permission to visit Oscar in Reading Gaol before she died in February 1896 and was buried in an unmarked grave at Kensal Green Cemetery. In 1999 a monument to her was erected in the cemetery by the Oscar Wilde Society.

Provenance

This book is from the Oireachtas Library’s York Street Workmen’s Club collection, which was donated to the library in the early 1920s. According to a note on the book, this copy was originally presented to the Workmen’s Club by Archbishop Thomas Croke.

References

Dudley, O. D. (2009) ‘Wilde, Jane Francesca Agnes (‘Speranza’)’. Dictionary of Irish Biography.

February 2022

This month we are displaying an exhibit of the travel book Rambles in Ireland. Published in 1912, the book recounts a trip taken by the writer Robert Lynd and his wife through Galway, Clare, Limerick, Kerry, Cork, Tipperary, and Dublin.

“Do you not think,” said I, resolved to turn the conversation at all costs, “that Parnell was a better man? “Parnell?” he barked, in an incredulous voice. “O God no. Oh, my God, no…”

Born in Belfast and based in London, Lynd worked as a journalist, essayist and editor. He was a staunch Irish nationalist and an active member of the Gaelic League. The book on display here was part of a ‘Rambles’ series of international travel essays published by Mills & Boon. It is beautifully illustrated throughout with drawings by Jack B. Yeats and photographs from the Lawrence photography studio.

The Sportsmen, by Jack B.Yeats

Though full of vivid descriptions of the Irish countryside and coastline, Lynd wasn’t particularly interested in scenery on his travels - “Going to see scenery always seems to me to be like taking an introduction to some famous man, not for the sake of a reasonable conversation, but for the sake of having met him”. He was far more interested in the social events of the towns and cities he visited. There are many entertaining and good-humoured interactions with locals and other tourists.

Lynd’s nationalist politics were sometimes challenged. At the Puck Fair in Killorglin he was offered a stool outside a local shop by the owner, who insisted on showing him a much-loved photo book of the King and Queen of England:

“Grand man, that!” said my host, tapping a freckled finger on the royal portrait [of King Edward].

“Do you not think,” said I, resolved to turn the conversation at all costs, “that Parnell was a better man?”

“Parnell?” he barked, in an incredulous voice. “O God no. Oh, my God, no,” he said, as though the very suggestion choked him with disgust.

“I can tell you,” he declared, his eyes dancing, as he snapped Queen Alexandra’s photograph-album out of my hands, “there’s damned little nationality in my bones. Maybe there would be,” he glared, retreating into the door of his shop, “if it paid me.”

The Puck Fair in Killorglin, from the Lawrence photography studio

Lynd also attempted to speak Irish throughout his trip but was sometimes met with puzzled or sheepish reactions from people. He was crushed when the proprietor of a bar in Killorglin asked if he was English when he ordered a drink in Irish. And on learning that he and his wife were ‘Gaelic Leaguers’, a priest in Lisdoonvarna announced “Ah! Bó – a cow: I got that far. It’s a terrible hard language. Do you think it will ever be spoken again?”

Finishing in Dublin, Lynd’s nationalism remained undiminished, however, and he concluded that “Dublin to-day is only leading a bathchair existence compared to the leaping energy of life that will be hers when she is a capital in liberties and duties as well as in name”.

The book provides a fascinating insight into not just the Irish tourist industry of 1912, but the immensely diverse political and social views of Irish citizens just a few years before war and revolution took hold.

Provenance

This book is from the Oireachtas Library’s Dublin Castle Collection, the former reference library of the Chief Secretary’s Office in Dublin Castle.

References

Ferriter, D. (2009) Lynd, Robert Wilson. Dictionary of Irish Biography.

December 2021

This month we are displaying a photographic facsimile of the Anglo-Irish Treaty. According to a handwritten note on the first page, the Articles of Agreement were copied by the National Museum (where the original Treaty is held), by permission of the government and under the supervision of the clerk of the Dáil.

The Treaty had been signed on 6 December 1921 after an intense period of negotiations in London. One of those providing secretarial assistance to the Irish delegation was Diarmuid O’Hegarty. Born in Skibbereen in 1892, O’Hegarty had joined the Civil Service in Dublin in 1910 and worked for T.P. Gill in the Department of Agriculture and Technical Instruction.

He also joined the Irish Volunteers and took part in the Easter Rising. Though jailed in England along with many other Volunteers he was accidentally released from prison and returned to his job in Ireland. According to his fellow Volunteer Barney O’Driscoll, T.P. Gill said “Take your holidays first, Hegarty and report back. I hope you enjoyed the time you were fighting”.

He was dismissed by the civil service in 1918 for refusing to take the oath of allegiance. But his administrative skills were put to vital use as clerk of the first Dáil and secretary to the Dáil cabinet in the two years that they were on the run. He organised their meetings, recorded the minutes and was the central point of communications for the departments. A close friend of Michael Collins, he accompanied him to London during the Treaty negotiations. As a supporter of the final agreement, he continued his civil service career after the Free State was established but will always be remembered as the “civil servant of the revolution” (Pakenham, 1972).

More information on the Anglo-Irish Treaty can be found on our dedicated web page on the Treaty Debates.

Provenance

This document is from the Oireachtas Library’s archival collection.

References

Pakenham, F. A. (1972). Peace by ordeal. London: Sidgwick & Jackson Ltd.

Murphy, W. & Coleman, M. (2009). "O’Hegarty (Ó hÉigeartuigh), Diarmuid". Dictionary of Irish Biography. www.dib.ie/biography/ohegarty-o-heigeartuigh-diarmuid-a6802

Ruairc, Ó. P. Ó., Borgonovo, J., & Bielenberg, A. (Eds.) (2015). The Men Will Talk to Me (Ernie O’Malley series, West Cork Brigade). Cork: Mercier Press.

November 2021

This month we are displaying a copy of Nolan’s Illustrated History of the War against Russia. This was published shortly after the 1853-56 Crimean War, which Russia lost to a coalition of the United Kingdom, France, Sardinia, and the Ottoman Empire.

New technologies had a significant impact on media coverage of the war. Where previously it took weeks and months for reports to arrive from abroad, developments in telegraph communications meant that news could reach Britain within days, or even hours.

Times correspondent William Howard Russell (1820-1907) sent back vivid and sometimes scathing reports of the British military which had a major influence on public and political opinion. By 1855 the war had become unpopular in Britain, being associated with blunders like the infamous ‘Charge of the Light Brigade’ and the loss of more soldiers to disease than combat.

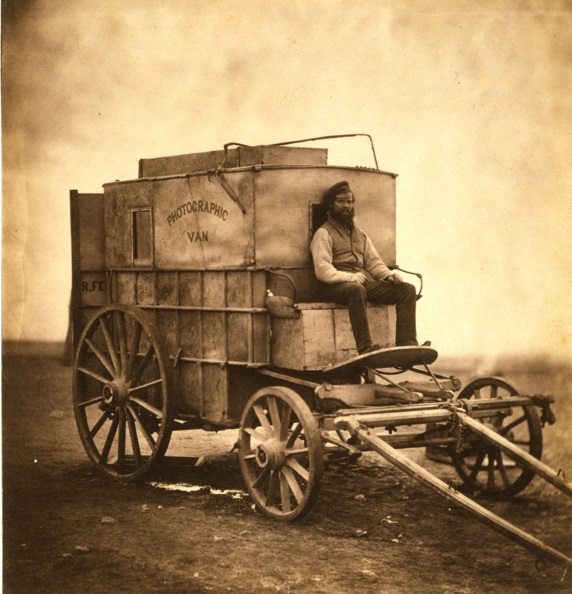

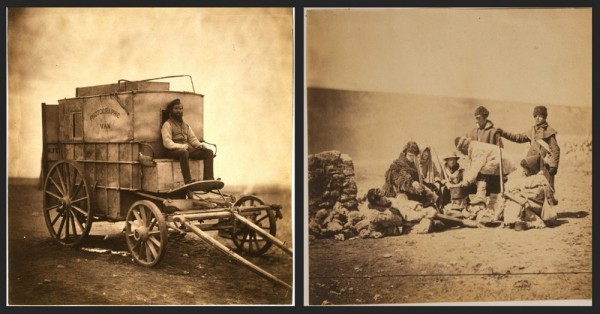

1) Fenton’s assistant Marcus Sparling, sitting on his photographic van. 2) Soldiers posed around a fire. Source: Wikimedia Commons

The war was also the first to feature the new technology of photography, most notably the work of British photographer Roger Fenton (1819-1869). Fenton travelled to Crimea in 1855, not as a journalist but to create a portfolio of images to sell at home. His equipment at the time was bulky and the long exposure times restricted his subject choices. Unable to capture live action on the battlefield, he also avoided graphic imagery of casualties, focussing instead on the military camps, equipment, and high-ranking officers.

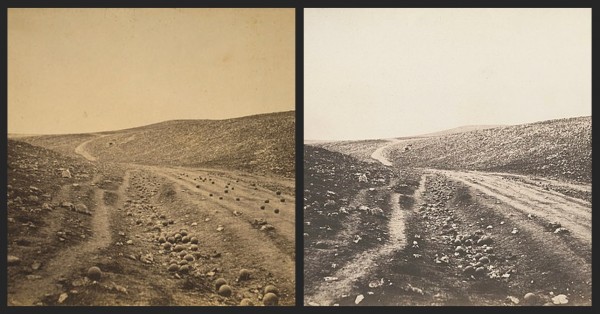

Fenton also photographed the landscape and his most famous image of the war contained no people at all. Known as the Valley of the Shadow of Death the haunting image showed cannonballs strewn along a desolate road. Intriguingly, two versions of the same photograph exist, one with cannonballs on the road and one without. There has been much debate about which of the photographs was taken first, and whether Fenton staged the scene.

Two versions of Fenton’s Valley of the Shadow of Death. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Though not initially intended as news coverage, Fenton’s images were published in the Illustrated London News and attracted much attention from a public who had never experienced war in such an immediate and visual way. (They were also used for illustrations in Nolan’s book.) War photojournalism became commonplace as technologies improved, with both the press and the military vying for authority over the visual record of events. Disputed images such as Fenton’s Valley of the Shadow of Death or Robert Capa’s The Falling Soldier from the Spanish Civil War raise interesting questions about ‘truth’ and ‘reality’ in photography, and photojournalism continues to generate controversy over its perceived influence on public and political opinion.

Provenance

This title is from the Oireachtas Library’s FitzGerald Collection, purchased in auction in the 1920s from Carrigoran House, Co. Clare.

References

Baldwin, G., Daniel, M. & Greenough, S. (2004). All the mighty world: the photographs of Roger Fenton, 1852-1860. Yale University Press.

Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia (1998). Crimean War. Encyclopedia Britannica. www.britannica.com/event/Crimean-War

October 2021

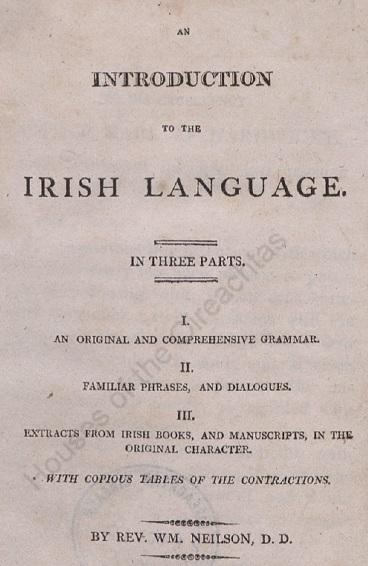

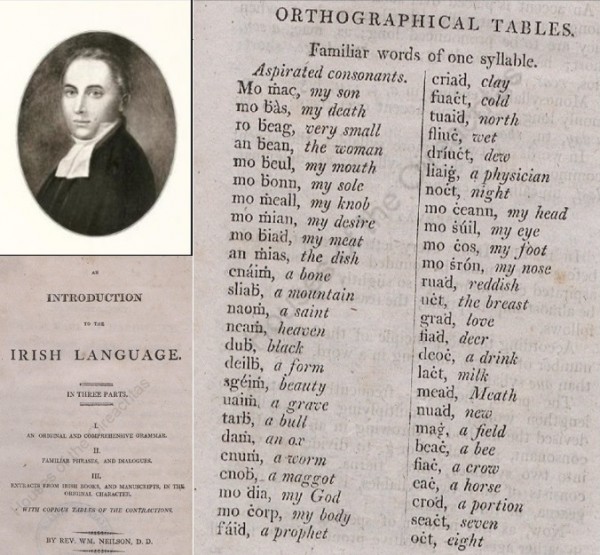

This month we are displaying a first edition of Rev. William Neilson’s An Introduction to the Irish Language, also known as Neilson’s Grammar. The book was first published in 1808 and is considered a pioneering text on Irish grammar and word structure.

William Neilson (1774-1821) was born into a scholarly, Irish-speaking Presbyterian family in County Down.

He was fluent in Latin, Greek, Hebrew and Irish and became a minister and teacher like his father. He taught Irish at his interdenominational school in Dundalk. Though he was loyal to the English crown his similarity in name to United Irishman Samuel Neilson (1761-1803) once caused him to be arrested for treason during the 1798 rebellion after he delivered a sermon in Irish. (He was released once he had provided a translation.

For the Presbyterian ministry use of the Irish language was encouraged as a means of spreading their religious message in Ireland. But there had also been a scholarly resurgence of interest in Celtic culture in Scotland and Ireland in the late 18th century. Scholars and antiquarians, some of whom had Scots Gaelic ancestry, advocated strongly for the preservation of Irish as essential for reading Gaelic manuscripts and other important historical documents.

Other scholars focused on promoting the use of Irish as a modern language. Neilson believed that a knowledge of Irish was vital simply for practical, everyday interactions with his own countrymen. It was for this reason that he produced his grammar book in 1808, noting that while a number of texts had been published on Celtic antiquities, “a grammar, by which the learner might be taught to compose, as well as to analyze, appeared to be wanted”. Presbyterian scholarly engagement with Irish continued into the 19th century but interest declined as the language became more politicised and associated primarily with the nationalist movement.

Provenance

The book has been part of the Oireachtas Library’s general historical collection since 1924.

References

Ó Saothraí, Séamas (1989). William Neilson DD MRIA (1774-1821). Journal of the County Louth Archaeological and Historical Society, 22 (1), 20-28.

Murphy, David (2009). Neilson, William (Mac Néill, Uilliam). Dictionary of Irish Biography.

William Cobbett, circa 1831. Source: Wikimedia Commons

September 2021

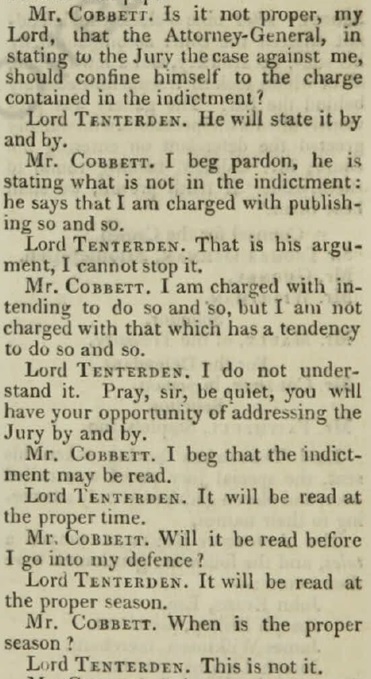

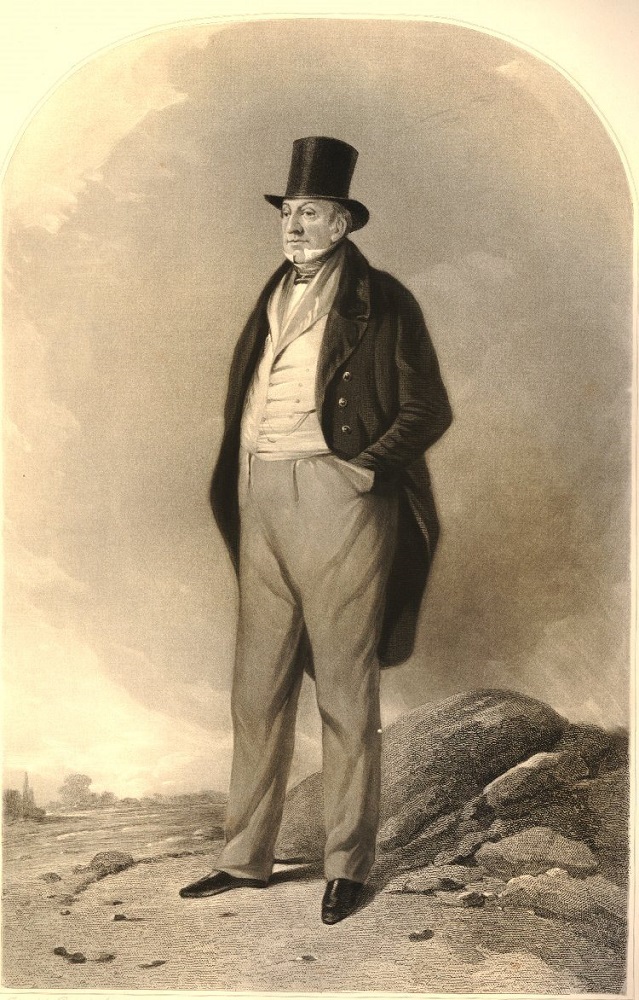

This month, we are displaying an entertaining account of the 1831 trial of William Cobbett (1763-1835).

Cobbett was an English journalist and political activist who championed the rights of rural workers during the industrialisation of 19th century Britain.

From the late 18th century, a succession of ‘enclosure’ laws in England saw the large-scale removal of traditionally common rural land into private ownership. This left a significant number of workers without any land to graze animals, meaning they were heavily reliant on wages as farm labourers during autumn and winter harvesting. The end of the Napoleonic wars, however, led to a decline in wages, as the returning men and an influx of Irish immigrants caused a labour surplus. This was compounded by a fall in agricultural prices, the burden of Church tithes and pressure on Poor Law rates for an increasing number of struggling people.

William Cobbett, circa 1831 / Source: Wikimedia Commons

When threshing machines began to replace the workers entirely, it sparked a widespread backlash. After two consecutive bad harvests, farm labourers had had enough by late 1830 and began to riot, attacking farms and destroying threshing machines. Threatening letters sent by the protesters to local authorities and wealthy landowning farmers were often signed by the name ‘Captain Swing’, thought to be inspired by the swinging motion of a flail (a tool for threshing grain). The riots therefore became known as the Swing Riots.

Cobbett had made an enemy of both Tory and Whig governments on many occasions by championing political reform and speaking out against political corruption and the rise of national debt. He particularly opposed industrialisation, harbouring the nostalgic view of a self-sufficient, 18th century agricultural England. His publications and speeches on the subject were popular with the rural community and his support for the Swing rioters led to a prosecution for seditious libel in 1831.

Cobbett represented himself in court. The trial opened with a complaint by the prosecuting Attorney General that Cobbett had packed the courtroom with cheering supporters and announced in front of the jury that “if truth prevail, we shall beat them”. It is clear from the published account that Cobbett’s provocative interactions with both the Attorney General and the presiding judge was a source of much frustration. His aggressive approach was successful, and to the government’s embarrassment he was acquitted when the jury failed to agree a verdict.

After the passing of the 1832 Reform Act, Cobbett was elected to parliament, but he found the move from activist to politician difficult. He died in 1835. Cobbett was a prolific writer throughout his life and is credited with coining the term ‘red herring’. His varied stances on key political and economic issues of the day made him friends and enemies on all sides of the political spectrum. He began publishing Parliamentary Debates in 1802 before financial difficulties prompted him to transfer ownership of the collection to Thomas Curson Hansard (1776-1833), after whose name the parliamentary record would become officially known.

Provenance

This publication is part of the Oireachtas Library’s Irish Office collection, a series of pamphlets once held in the reference library of the Irish Office, London, and transferred to the Oireachtas in the 1920s.

References

Caprettini, Bruno, and Hans-Joachim Voth (2020). "Rage against the Machines: Labor-Saving Technology and Unrest in Industrializing England." American Economic Review: Insights, 2(3), 305-20.

Wells, Roger (1997). “Mr William Cobbett, Captain Swing, and King William IV.” The Agricultural History Review, 45(1), 34–48.

August 2021

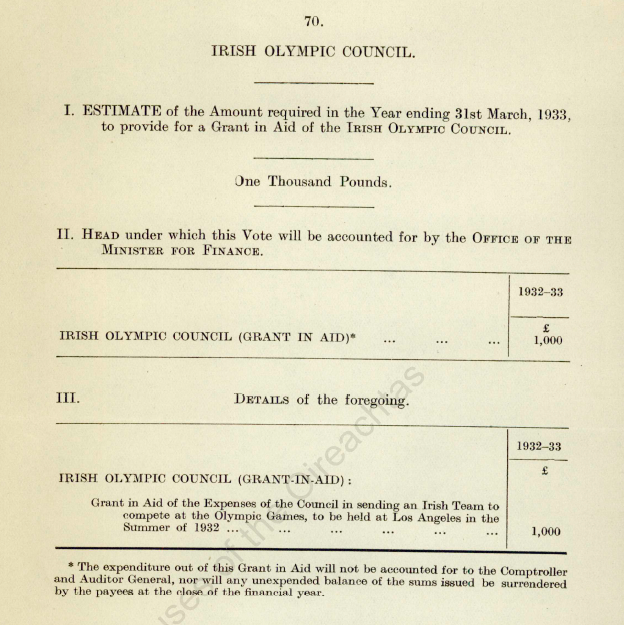

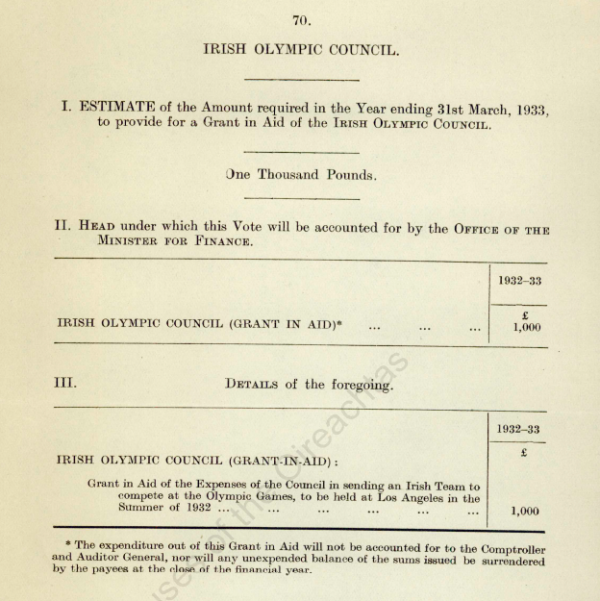

This month, to celebrate the recent success of the Irish Olympic team in Tokyo, the Oireachtas Library has been looking through our collections for references to past games. This document laid before the Houses shows a grant of £1,000 from the Department of Finance to support the Irish team in the 1932 games in Los Angeles. In the Dáil on 9 June 1932, Minister for Finance Seán MacEntee explained that a precedent had been set by granting £1,000 to the team in 1928. When Deputy Richard Mulcahy asked about progress in having the sports of handball and hurling included as Olympic contests, MacEntee replied:

“Handball is not an item in the contests this year, but a team is being sent out. It is on trial, so to speak. I understand that steps have been taken to secure the same status with regard to hurling, but the suggestion has not advanced yet to the same stage as in the matter of handball. It is much more expensive to send out a hurling team than a handball team, and that may have had something to do with the attitude of the Olympic Council.”

Ireland had competed at the 1924 Paris Olympics but didn’t win any sports medals (though we won silver and bronze in the Olympic art competitions that were a feature until 1948). Around that time a medical student called Pat O’Callaghan was inspired by the strong tradition in Irish throwing sports to take up the hammer. Going from strength to strength in competitions, the young doctor became a national hero in 1928 when he won gold at the Amsterdam games, marking Ireland’s first Olympic medal as an independent country.

A government grant of £1,000 to support the Irish team at the 1932 Olympics

Eight athletes were sent to Los Angeles in 1932, including O’Callaghan and Bob Tisdall, the son of Irish parents, who lived in Britain. An impressive all-round athlete, Tisdall wrote to the Irish Olympic Council asking to take part in the 400m hurdle race, despite having never competed in it. Though running slowly in his first Irish trial, he managed a qualifying time after two weeks training in Ballybunion and was able to join the national team.

Initially struggling with nerves, Tisdall went on to win his heat and semi-final. On 1 August, he lined up for the final against very experienced athletes, including the reigning and preceding champions. Starting well, he smashed into the final hurdle but recovered in time to win the gold medal. Tisdall then made his way to the hammer circle, where he helped a frustrated O’Callaghan file down the spikes on his shoes. O’Callaghan had come in as one of the favourites, but his technique was impacted by the unexpectedly hard surface of the hammer circle. With his spikes filed down, and in second place for his final throw, he sent the hammer 5ft further than the leading competitor, retaining the gold medal for Ireland.

Dr Pat O’Callaghan (left) in 1928 and Bob Tisdall (right) in 1932

O’Callaghan became an international sporting celebrity in the years that followed. Political wrangling among rival athletic associations on the island meant that Ireland did not compete in the 1936 Olympics, so he could not defend his title. He later went to America, where he was offered the part of Tarzan in Hollywood. He made an unsuccessful attempt to move into professional wrestling before returning home, where he set up a general practice in Tipperary. Also maintaining an international celebrity status, Tisdall embarked on a range of business ventures over the following decades, living in Europe and Africa before finally settling in Australia. He did his first parachute jump at 86, and in 2000 he jogged with the Olympic flag at the age of 93 for the Sydney games.

References

Byrne, K. (2012). Monday 1 August 1932: Ireland's finest Olympic hour? History Ireland, 20(4), 28-29.

Lysaght, Charles (2010). Tisdall, Robert Morton Newbury (Bob). Dictionary of Irish Biography.

Rouse, P. (2009). O’Callaghan, Patrick (‘Pat’). Dictionary of Irish Biography.

July 2021

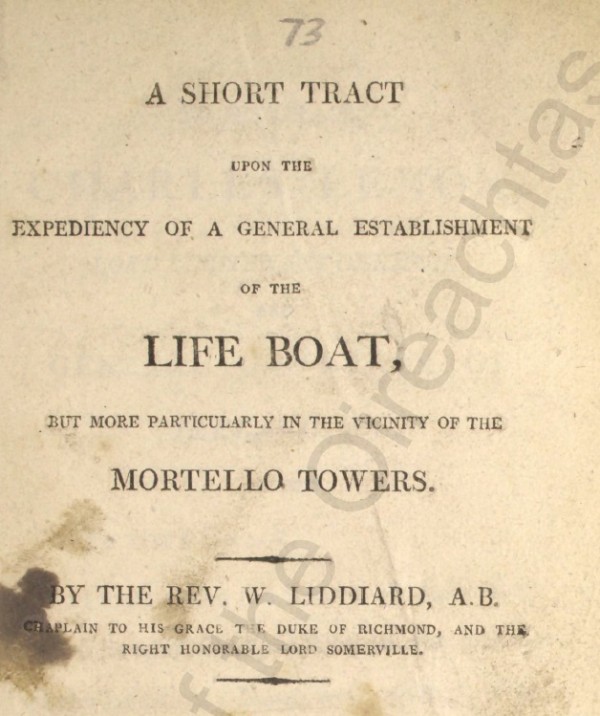

This month we are displaying an 1807 pamphlet by Reverend William Liddiard (1773–1841), calling for the establishment of an organised lifeboat service along the Irish coast. Reverend Liddiard was particularly keen to use the recently constructed Martello towers as dedicated lifeboat stations.

Liddiard was writing in response to the recent sinking of two ships in Dublin Bay - the Rochdale and the Prince of Wales - which saw the loss of almost 400 lives in one night.

“I have seized the moment when the feelings of the nation are afloat, and before they can possibly be thought to have subsided, of recommending a more general establishment of the Life-boat; a plan, which affords in some degree a balm for the despondency of the moment, promising as it does to prevent a recurrence of misfortunes similar to those, which have lately gloomed our shores."

The two ships had been carrying soldiers bound for the Napoleonic war front when they left Dublin on 19 November 1807. They were caught in a fierce wind and snowstorm shortly after setting out. The Prince of Wales was forced onto rocks at Blackrock, with the captain, crew, family members and two soldiers managing to reach shore on a smaller boat. 120 soldiers drowned. There was an allegation that the captain had trapped the soldiers below deck so that he could take the only spare boat to safety, but without enough evidence the charge was dropped. The Rochdale went onto the rocks at Seapoint, with the loss of all 265 passengers and crew.

It is clear from the pamphlet that Liddiard was impressed with the work to develop a dedicated lifeboat service at Bamburgh Castle on the north-east coast of England. In 1786 the estate’s trustee, the Archdeacon of Northumberland, commissioned Lionel Lukin (1742-1834) to transform a fishing boat into a specialised lifeboat. Lukin had been credited with the first design for an onshore lifeboat, patented in 1785. For several years afterwards sea rescues were launched in Lukin’s converted fishing boat by a crew out of Bamburgh Castle, making it one of the first dedicated lifeboat stations.

The organised nature of the work at Bamburgh prompted Liddiard to ask if the ‘Mortello’ towers around the Irish coast “might not be converted into a twofold means of safety, into a tower of salvation as well as what it now is, a battlement of defence?”. Many of the buildings – more commonly known as Martello towers – had been built in 1804 and 1805, taking their name and design from defensive towers at Mortella in Corsica.

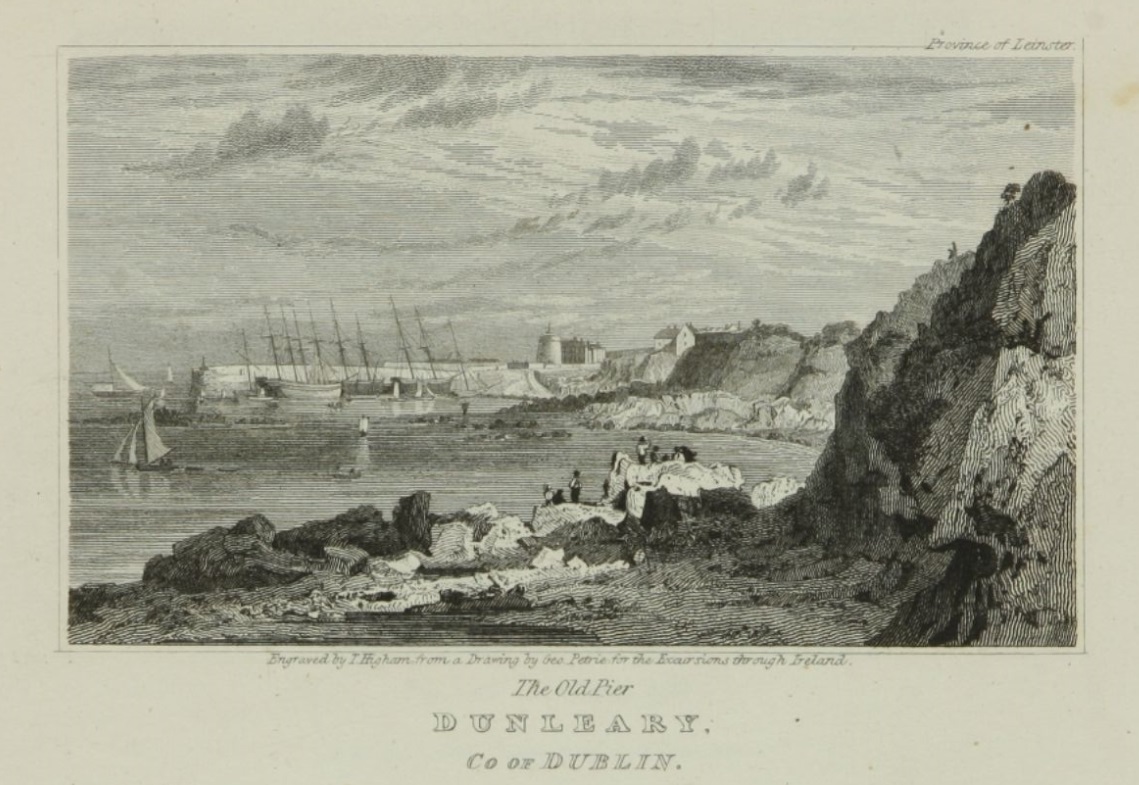

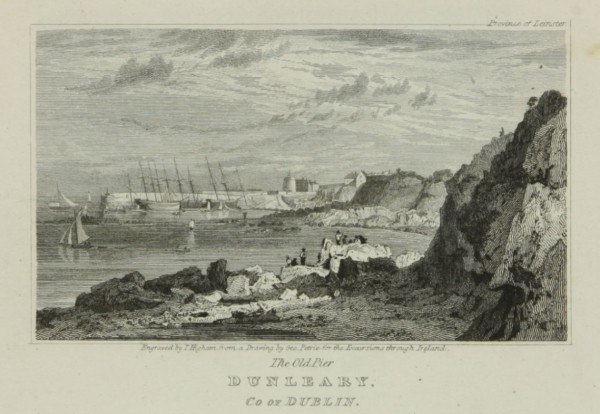

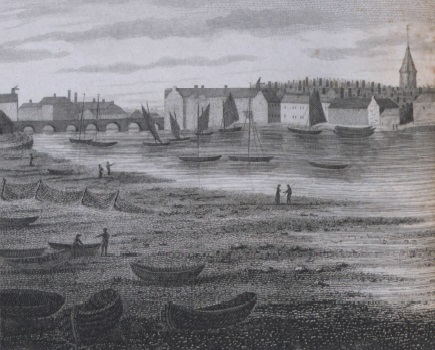

The old pier at the village of Dunleary

Despite Liddiard’s impassioned plea, however, it was not until 1824 that the National Institution for the Preservation of Lives and Property from Shipwreck was established for Britain and Ireland (now the Royal National Lifeboat Institution). But the sinking of the Rochdale and Prince of Wales added to a growing campaign for the development of a safe pier at the small village of Dunleary (now Dún Laoghaire). A pier built in the mid-1700s had silted over, but the location was considered ideal as a harbour for ships seeking refuge from the dangerous conditions of Dublin Bay. Work on this finally began in 1817, and the new pier was finished in time to host the ship of King George IV in 1821.

Provenance

This 1807 pamphlet is from the Oireachtas Library’s Dublin Castle Collection, the former reference library of the Chief Secretary’s Office in Dublin Castle. The image of Dún Laoghaire is from Thomas Cromwell’s 1820 Excursions Through Ireland, which is part of the Milltown Collection, the former library at Russborough House, Co. Wicklow.

References

Royal National Lifeboat Institute. (n.d.) Timeline. https://rnli.org/about-us/our-history/timeline.

Bourke, Edward J. (2008). “The Sinking of the Rochdale and the Prince of Wales.” Dublin Historical Record, 61(2), 129–135. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/27806786.

June 2021

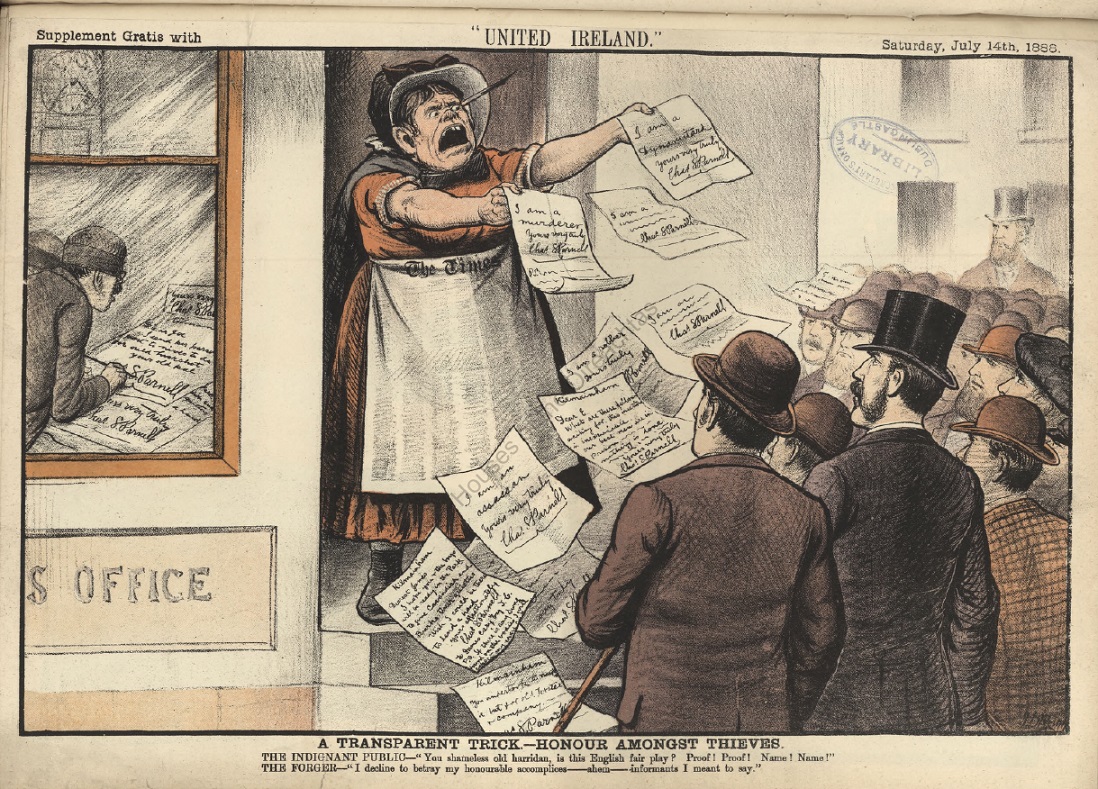

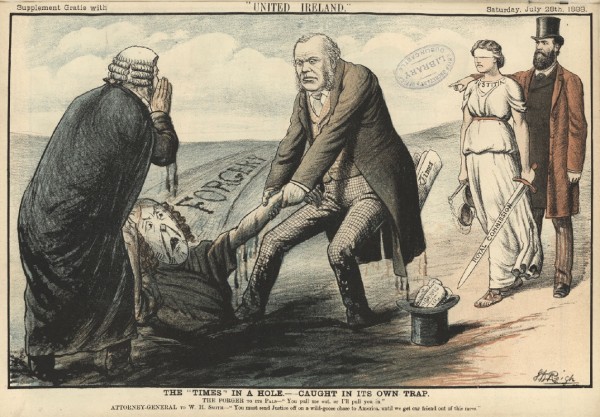

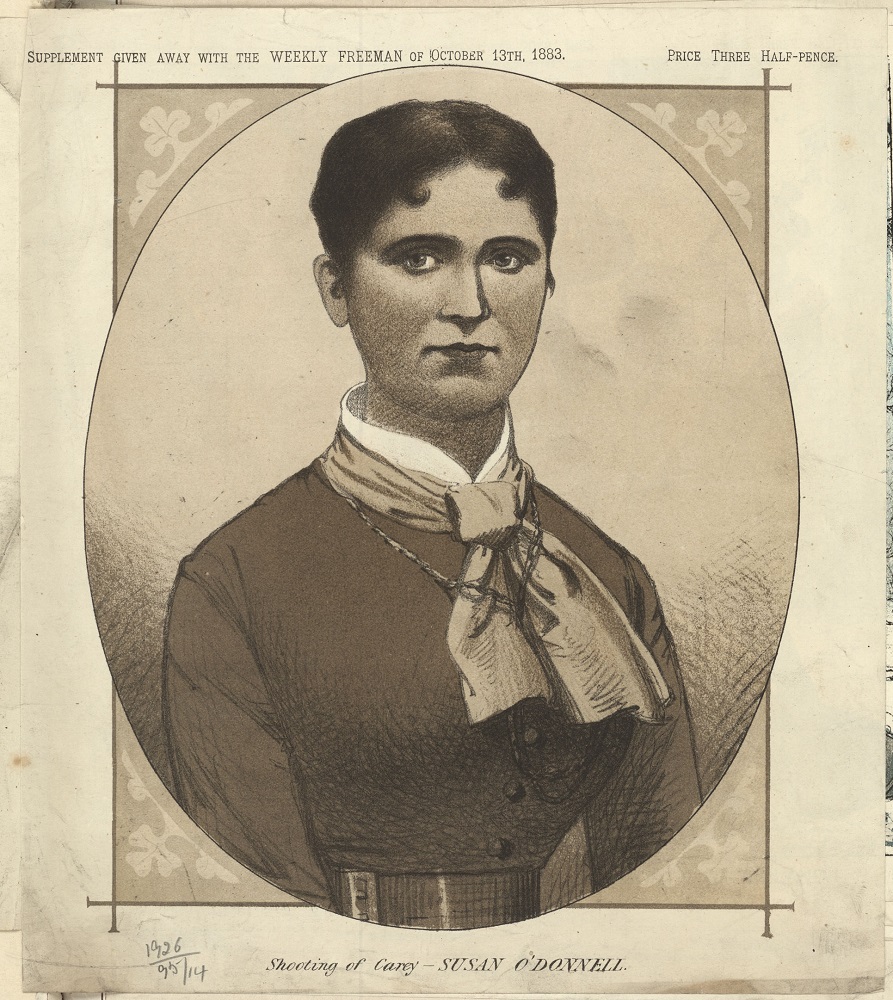

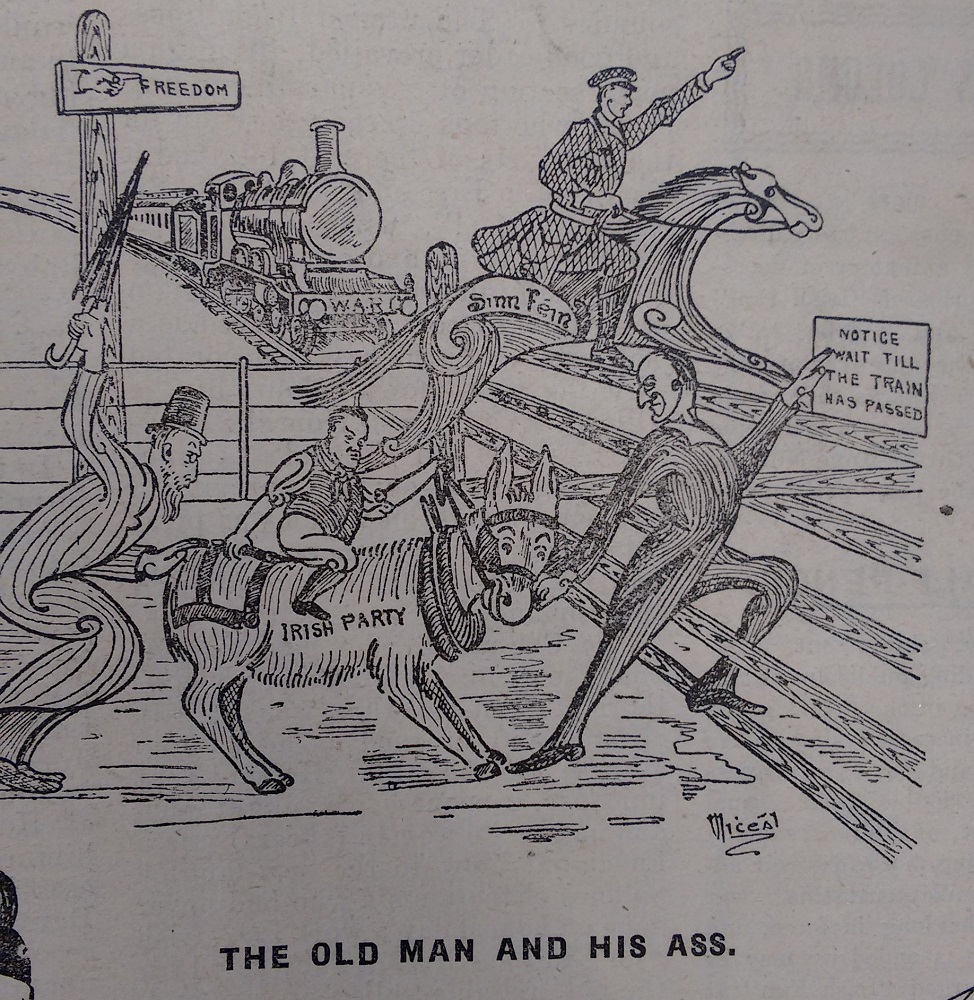

This month we are taking a closer look at the Parnell Commission of 1888-89 through contemporary cartoons published in the pro-Parnell newspaper United Ireland.

In the 1880s The Times, a conservative newspaper, was vehemently opposed to the push for home rule in Ireland by the Liberal Party and the Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP). In March 1887 the paper started publishing a series of articles called "Parnellism and Crime", which sought to discredit the IPP by linking its members directly to criminality and republican violence.

On 18 April the paper caused a sensation by publishing a letter, allegedly written by IPP leader Charles Stewart Parnell, in which he indicated support for the notorious 1882 murders of the Chief Secretary and Permanent Under-Secretary for Ireland. Parnell protested his innocence, claiming that this and other published letters were forgeries. A year later the government established a special commission to investigate the numerous charges made by The Times against Parnell and his peers.

In this cartoon The Times, depicted as a woman wearing the newspaper as an apron, throws fake Parnell letters towards an indignant public, while through a window people can be seen copying Parnell’s signature.

The government viewed the commission as an opportunity to permanently damage Parnell’s reputation, and by association the reputation of the Liberal Party. The government provided significant resources and documents to The Times’s solicitors and The Times was represented by the Attorney General at the commission. Parnell accepted it as an opportunity to clear his name. His friends at the United Ireland newspaper in Dublin rallied to his support, publishing editorials and cartoons depicting The Times as being mired in forgery.

In this cartoon The Times is depicted as a woman with the face of a clock. She is being pulled from a hole by the Attorney General and W.H. Smith, Leader of the House of Commons, while Parnell points them out to a blindfolded "Justice".

It was over a month before the hearings turned to the letters. The Times said that the letters had been purchased from a unionist organisation - the Irish Loyal and Patriotic Union. This organisation claimed to have purchased them from a man called Richard Pigott. Pigott was a disreputable and down-on-his-luck Irish journalist. He was well known to Irish nationalists and land activists, having fallen out with many of them over the years. Pigott took to the witness stand on 20 February 1889 and told the commission that he had sourced the letters from the republican group Clan na Gael in Paris.

Parnell’s team, led by the future Lord Chief Justice of England, Charles Russell, had conducted its own detailed research and they had noticed something unusual about the letters. There were a surprising number of spelling mistakes, including the word 'hesitancy' spelled as 'hesitency'. A political friend of Parnell’s, Patrick Egan, remembered seeing that particular spelling error before, in a letter sent to him by Richard Pigott. Egan alerted Parnell and Russell, and when it was time to cross-examine Pigott on the witness stand, Russell handed him a piece of paper.

He asked the perplexed witness to write out several words, including the name ‘Patrick Egan’. Then he added casually, “There is one word I had forgotten. Lower down, please, leaving spaces, write the word ‘hesitancy’, with a small ‘h’". Pigott wrote this final word and handed the sheet of paper back to Russell. Sure enough, the word ‘hesitancy’ had been spelled as ‘hesitency’. Russell put the sheet down and proceeded to bombard Pigott with questions.

Russell and the team had seen correspondence from Pigott to the Archbishop of Dublin (a supporter of home rule and land reform), warning him of impending press revelations about Parnell. The correspondence had raised their suspicions that he was playing unionists and nationalists against each other for financial profit. Pigott’s increasingly flustered answers to Russell’s detailed questions demonstrated quite visibly that he was lying about his involvement in the affair. On the third day that he was due for questioning, Pigott didn’t appear, having fled abroad. He sent a written confession to the commission that he had forged the letters himself. When police caught up with him in Madrid, he died by his own hand before they could arrest him.

The commission eventually upheld some lesser charges against the IPP. But in relation to the accusation of direct links with violence and criminality, Parnell was vindicated. He sued The Times and his political reputation was restored. Just a few months later, however, he was thrust into the media spotlight again when he was named as a co-respondent in the divorce proceedings of William and Katharine O’Shea. This time the outcome would be very different.

Provenance

The cartoons ‘A Transparent Trick’ and ‘The Times in a Hole’ are from the Oireachtas Library’s Dublin Castle Collection, the former reference library of the Chief Secretary’s Office in Dublin Castle.

References

Aitken, R. (Spring, 2003). The Spelling Game: Russell’s Cross-Examination of Pigott. Litigation, 29(3), 47-71.

Lyons, F. (1974). 'Parnellism and Crime', 1887-90. Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, 24, 123-140.

Wellman, F. L. (1903). The art of cross-examination. London. Macmillan.

May 2021

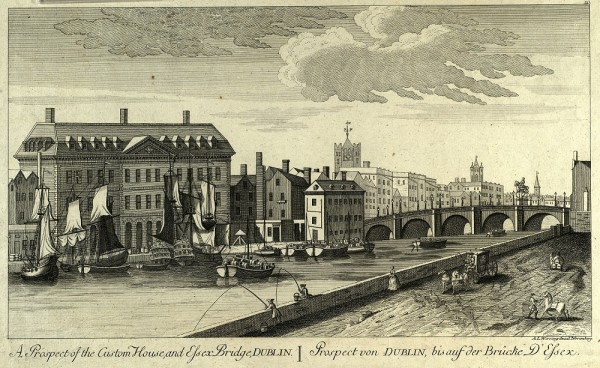

This month, to mark 100 years since the burning of the Custom House, Dublin, we are displaying an 18th century print of the former Custom House beside Essex Bridge. The Custom House was designed by architect Thomas Burgh and built in 1707.

The 18th century was a time of great expansion and development in Dublin. The Wide Streets Commission, a powerful planning organisation, shifted the entire centre of the city eastwards, away from the old medieval quarter.

The Commission built and widened streets and bridges, creating a new central artery from Sackville Street (now O’Connell Street) through to College Green.

Print of the 1707 Custom House beside Essex Bridge

By the 1770s, the Custom House’s location was deemed unfit for purpose. The Wide Streets Commission and Commission of Revenue decided to develop a new Custom House further down river. The plans caused uproar amongst local merchants, who worried that their businesses and property values would be negatively impacted. The Oireachtas Library has an anonymous pamphlet from 1781 which argued that the new location would provide a deeper berth for a greater number of ships.

Chief Revenue Commissioner John Beresford invited architect James Gandon from London to design the new Custom House. Constructed in the popular neoclassical style of the time, the impressive building opened in 1791. Gandon also designed the Carlisle Bridge (now O’Connell Bridge), which opened in 1794 and shares some architectural features with the Custom House.

A 19th century sketch of Gandon’s Custom House

As the port of Dublin moved further down river in the 19th century, the location for the Custom House became unsuitable again. Instead, it housed a number of other government agencies, including the Local Government Board. As a symbol of British administration, it was deemed a target by the IRA during the War of Independence.

On 25 May 1921 a large force of IRA volunteers stormed the building. They set a fire that would last five days, gutting the interior and destroying centuries of government records. The shell of the building survived, and it was restored in the late 1920s (and again in the 1980s) by the Office of Public Works. Today the building provides offices for the Department of Housing, Local Government and Heritage.

Provenance note

Both the print of the 1707 Custom House and the pamphlet are from the Oireachtas Library’s Dublin Castle Collection, the former reference library of the Chief Secretary’s Office in Dublin Castle. The print of Gandon's Custom House is from Whammond's Illustrated Guide to Dublin and Wicklow (1878), which is part of the general historical collection.

Further reading

James Kelly. "Beresford, John". Dictionary of Irish Biography. (ed.) James McGuire, James Quinn. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press, 2009.

Development of Dublin City. www.archiseek.com/2010/development-of-dublin-city

Custom House, Dublin. www.archiseek.com/2010/1791-custom-house-customhouse-quay-dublin

January 2021

To mark the UN International Day of Education this month we are displaying the seminal 1965 report Investment in Education.

When Seán Lemass became Taoiseach in 1959, he embarked on a rapidly modernising approach to Ireland’s economy, opening up opportunities for free trade, foreign investment and increased engagement with the international community.

Ireland was one of the founding members of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) in 1961 and was the first member to take part in its education investment and planning programme. With support from the OECD, a team was established in 1962 by Minister for Education Patrick Hillery to thoroughly survey the education environment in Ireland.

Published at the end of 1965, the final report presented the first comprehensive statistical data on the Irish education sector. It found that thousands of Irish children were not moving on to second level education, and a significant proportion of those that did were leaving before completing the intermediate certificate. The main impediments highlighted were fees, geographical location and transport, lack of resources, and class issues.

These were worrying statistics in light of projected growth in the Irish population and economy, and the report became a powerful evidence base for the policies of incoming Minister for Education Donogh O’Malley in 1966. On 10 September that year he caused a media storm by announcing at a National Union of Journalists event that the Government would introduce free second level education and a free transport scheme for students from remote areas.

Minister for Education Donogh O’Malley, 1967

The scheme, though implicitly supported by Lemass, had not yet been approved by Cabinet, and caused some controversy amongst his colleagues. But faced with positive public support and the stark statistics of the Investment in Education report, the Government set about implementing this enormously progressive change in Irish education.

References

Patrick Maume (2009). O'Malley, Donogh. In James McGuire, James Quinn (ed.), Dictionary of Irish Biography. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press.

John Walsh, Selina McCoy, Aidan Seery & Paul Conway (2014). Investment in Education and the intractability of inequality, Irish Educational Studies, 33:2, 119-122.

April 2021

This month the Oireachtas Library is marking 100 years since the appointment of the last Lord Lieutenant of Ireland by displaying a satirical 19th century cartoon about this unique role.

There had been an official administrative representative of the English king or queen in Ireland since 1172. The position was known by several terms including chief governor, lord deputy, lord justice and viceroy, but was officially termed the ‘Lord Lieutenant’ after the 1801 Act of Union.

The role decreased in importance after 1801, becoming more of a ceremonial position. Real administrative power lay with the Chief Secretary for Ireland, a government minister who, though subordinate to the Lord Lieutenant, had more effect in implementing government policy. The Lord Lieutenant had apartments in Dublin Castle but mainly stayed in the Viceregal Lodge in Phoenix Park (renamed Áras an Uachtaráin when it became the residence for the President of Ireland). He hosted balls, dinners, royal visits, and the ceremonies for his political and military appointments.

As with the large number of absentee British landlords in the 19th century, the perceived aloofness of the Lord Lieutenant came to symbolise for many the administrative dysfunction of British rule in Ireland. None of the appointees held the role for longer than a few years, with the exception of the Earl of Aberdeen (a relatively sympathetic home rule advocate) between 1905 and 1915. Between 1880 and 1890, a time of much political and social unrest in the country, there were 7 different Lord Lieutenants.

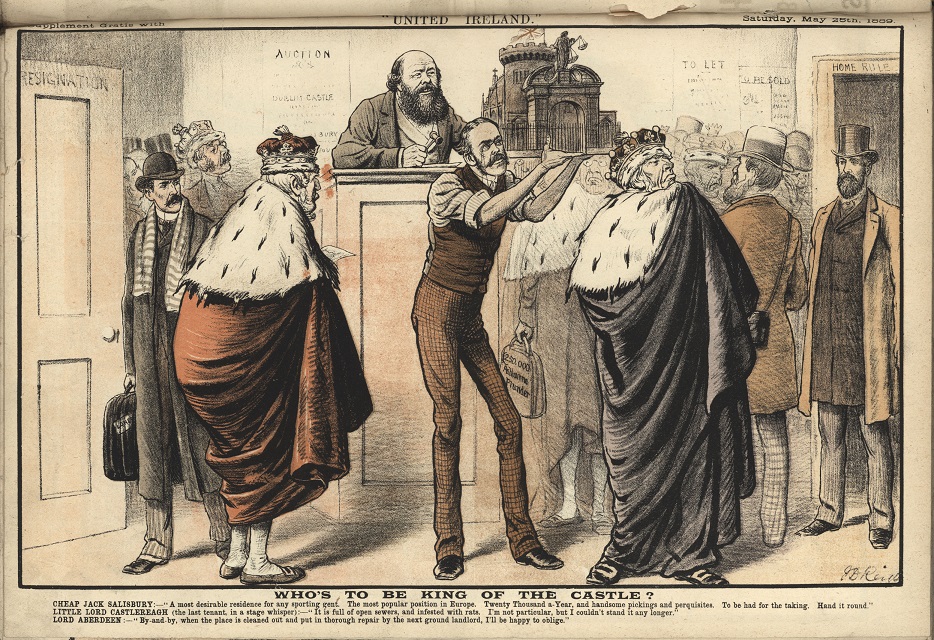

They were much satirised in the nationalist press. The cartoon on display here from 1889 is called “Who’s to be king of the castle?” and demonstrates the ongoing debate about whether the role was a valuable political stepping stone or a burden to be avoided. The scene depicts a number of British peers in an auction room as ‘Dublin Castle’ is held aloft by the Chief Secretary Arthur Balfour. Parnell looks on, standing next to a doorway marked ‘Home Rule’. Lord Salisbury calls the Castle “a most desirable residence for any sporting gent”, while Lord Castlereagh says, “it is full of open sewers, and infested with rats”.

In spite of several debates in the Commons about whether or not to abolish the role, it survived into the 20th century. On 27 April 1921, Edmund FitzAlan-Howard (1st Viscount FitzAlan of Derwent) was appointed, the first Catholic to hold the post since 1685. He oversaw the implementation of the Government of Ireland Act 1920 and the Anglo-Irish Treaty, and the establishment of two home rule parliaments on the island of Ireland between 1921 and 1922. The post was officially abolished when the Free State came into being in December 1922, being replaced by the Governor-General of the Irish Free State. That role was abolished in 1936.

Provenance note: This cartoon is one of over 600 19th century political cartoons in the library’s Dublin Castle Collection. This was the former reference library of the Chief Secretary’s Office in Dublin Castle.

References

Duncan, Mark (1921). Ireland’s Lord Lieutenant: “a fount of all that is slimy in our national life”. Century Ireland. RTÉ. Retrieved on 16/04/2021 at: https://www.rte.ie/centuryireland/index.php/articles/irelands-lord-lieutenant-a-fount-of-all-that-slimy-in-our-national-life

March 2021

This month we are revisiting the long, dangerous search for a northwest shipping route through the Arctic by exhibiting Captain John Ross’s published account of his expedition between 1829 and 1833.

Though the Vikings had sailed quite far northwest in the 10th century, it wasn’t until the end of the 1500s that European colonial powers began a sustained search for a safe shipping passage around the tip of North America.

It was hoped that this new shipping lane would enable quicker expansion of trade routes with the east. No such passage had been established by the time John Ross set out on his second expedition in 1829. Ross’s ship – Victory – carried the captain, three officers and 19 crew. The previous winter had been unusually mild, leading to an early sense of optimism about the voyage.

Ross’s map of the Arctic region. ‘King William Land’ in the south was later discovered to be an island.

In addition to the overall goal of navigating through to the west coast of North America the journey was one of scientific, meteorological and ethnographic discovery. Captain Ross gave names to previously uncharted inlets, mountains and islands. Notes, sketches and specimens of wildlife were taken. Ross records in detail how the party traded metal and other materials with the local Inuit for food, dogs and assistance with hunting, even making a wooden leg for one Inuit man. The ship also came upon the abandoned wreckage of a previous expedition led by Captain William Parry in 1825.

The voyage had scientific purposes, and the crew took time to document the wildlife.

In September of their first year the ship became trapped in ice and was unable to make any significant retreat for the following three winters. Ross did his best to keep spirits up, both for the crew and for himself, but admitted in his journal that “amid all its brilliancy, this land, this land of ice and snow, has ever been, and ever will be, a dull, dreary, heart-sinking, monotonous waste, under the influence of which the very mind is paralyzed”.

The crew continued to make overland discoveries, recording the magnetic north pole in 1831. In 1832 the crushing ice forced them to abandon the ship completely, and they began making plans to use the smaller boats from Parry’s shipwreck to row themselves to safety. Exhausted and suffering from scurvy they set out in 1833 and were fortunate to be rescued by the whaling ship Isabella, the very ship that Ross had captained on his first northwest expedition in 1818.

An 1834 print by Edward Francis Finden showing the rescue of Ross’s crew by the Isabella.

Ross writes that on introducing himself to the first Isabella crew member “he assured me that I had been dead two years”. Safe on board he found himself so unused to a real bed that he couldn’t sleep, finding it easier to sit in a chair for the first night. As the expedition had been assumed lost forever, their return caused considerable excitement in British society. The surviving members (three had died) were compensated financially and Ross was knighted. He published his journals of the expedition in 1835.

Though a navigable route was identified in the 1850s, by the end of the 19th century no ship had successfully sailed through the northwest passage. In 1903 Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen (who later became the first person to reach the south pole) set out in a light boat with a crew of just six. Though trapped in the ice for two years he successfully navigated the passage by 1906. The passage has never been of significant practical use for shipping, though in recent years the melting Arctic ice has renewed interest in its potential.

This book is from the FitzGerald collection purchased by the Oireachtas Library in 1922. This was a private family library and contains books and journals on literature, history and science.

References

Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia (1998). Sir John Ross. Encyclopedia Britannica. www.britannica.com/biography/John-Ross-British-explorer

Royal Museums Greenwich. John Ross’s second North-West Passage expedition 1829-33. www.rmg.co.uk/stories/topics/john-james-clarke-ross-north-west-passage-expedition-1829-33

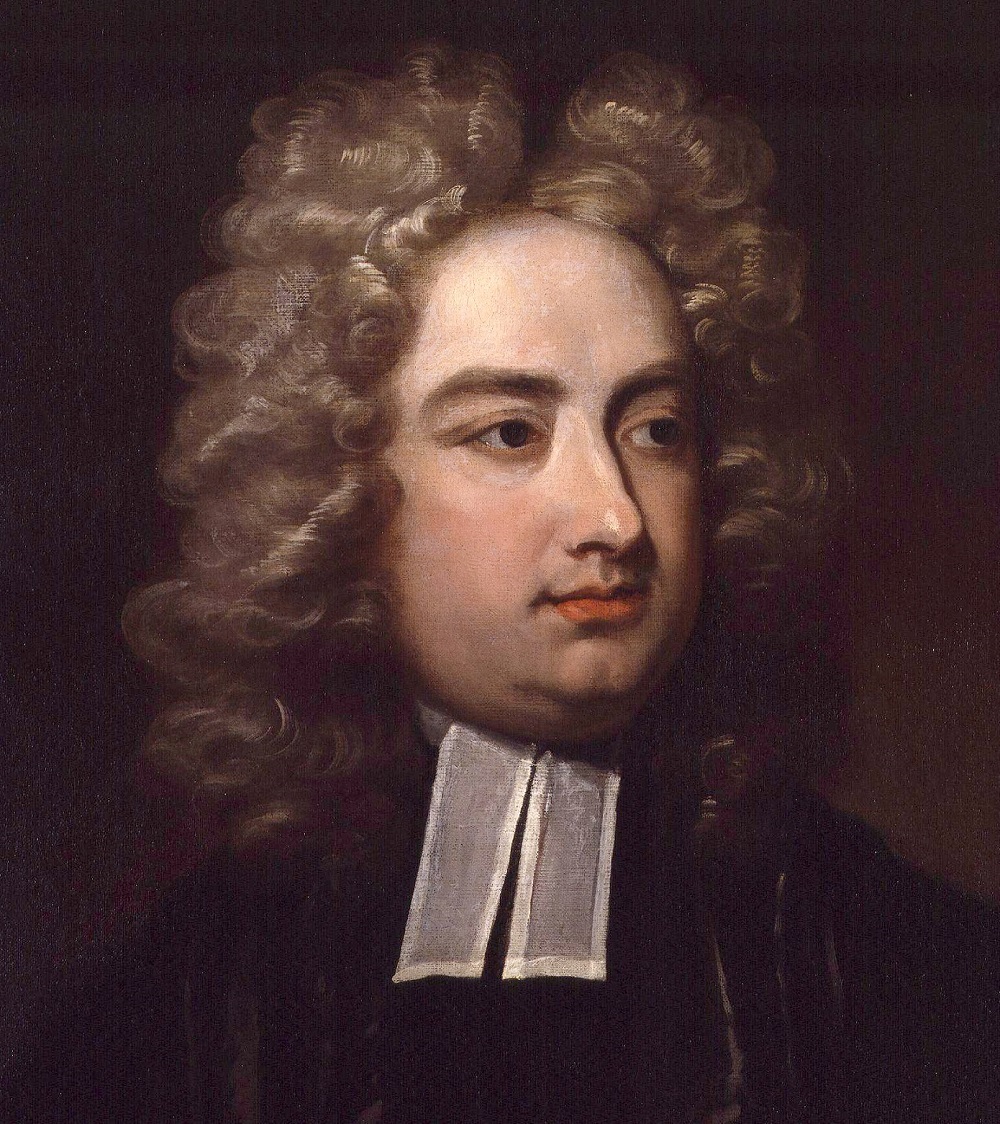

Jonathan Swift, by Charles Jervas

February 2021

This month we are revisiting the failed attempt to set up a national bank of Ireland 300 years ago with pamphlets for and against the proposal in our virtual display case.

The 17th century had brought about significant change in banking and finance, with the rise of joint stock companies and the establishment of national banks. The bank of England was founded in 1694 and immediately became a significant source of funds and debt management for the government. In 1720 a number of Irish MPs petitioned the King for a charter to set up a national bank of Ireland.

MPs like Henry Maxwell argued that the bank would guarantee lower interest rates than other private banks, which would increase the flow of money, fund capital projects and help Irish manufacturing and trade. Any improvements in the Irish economy, they proposed, could only be of benefit to both kingdoms. They also believed that a national Irish bank would leave investors less exposed to losses caused by foreign wars and stock bubbles.

Irish MPs Henry Maxwell and Hercules Rowley addressed each other’s arguments for and against the bank in a series of pamphlets

The charter was granted on the condition that the Parliament of Ireland pass an Act to set out rules for the bank within one year. But when the Parliament met to debate the Bill in late 1721 it was voted out after the first paragraph. Both Houses passed severe resolutions declaring not only that an Irish bank would be a national threat, but that anyone who pursued the idea would be considered an "enemy to his country".

Why was there such stringent opposition to a bank of Ireland? Scholars have pointed to anxiety on the part of the Protestant elite that Roman Catholics, who were forbidden to invest in land under the Penal laws, could accrue wealth alternatively by investing in the bank. There were also concerns that the bank could be used to fund England’s wars, as the Bank of England had done since its establishment. Shareholders in other banks may have worried that increased competition in the market would depreciate the value of their investments.

Of enormous concern was the prospect of political corruption, that the wealth of the bank would be used to buy elections or make corrupt investments. Perhaps the fear most openly shared, and certainly evident in the flurry of pamphlets published in the autumn of 1721, was a repeat of the South Sea bubble. The South Sea trading company, which had been backed by the English government, saw its share price soar and crash within the space of a few months in 1720, causing enormous losses for its wealthy investors.

It is clear from the pamphlets of MP Hercules Rowley that he considered the ills of the Irish economy to be the fault of laziness and vanity, and that a bank of Ireland would merely exacerbate those problems. Behind many of the MPs’ arguments lay a fundamental mistrust of modern banking, and of the risks inherent in Europe’s growing stock markets. Many of those who voted against the Bill were part of the rural gentry, the owners of vast estates who believed that real wealth should come from land, not trade.

Prominent writer Jonathan Swift is more famously associated with the “Wood’s halfpence” crisis of 1722-25 but was also opposed to the bank of Ireland

Public arguments about Irish finance would continue throughout the 18th century, many of them set out in pamphlets by prominent figures such as Jonathan Swift (who may have assisted the MPs with their pamphlets opposing the bank in 1721). The Oireachtas Library has eight pamphlets dealing with the 1721 crisis alone, which were bound and kept in the reference library of the Chief Secretary’s Office in Dublin Castle.

References

Rees, G. (Sep/Oct 2012). "Hang up half a dozen bankers": attitudes to bankers in mid-eighteenth-century Ireland. History Ireland.

Ryder, M. (1982). The Bank of Ireland, 1721: Land, Credit and Dependency. The Historical Journal, 25, 3, 557-582.

December 2020

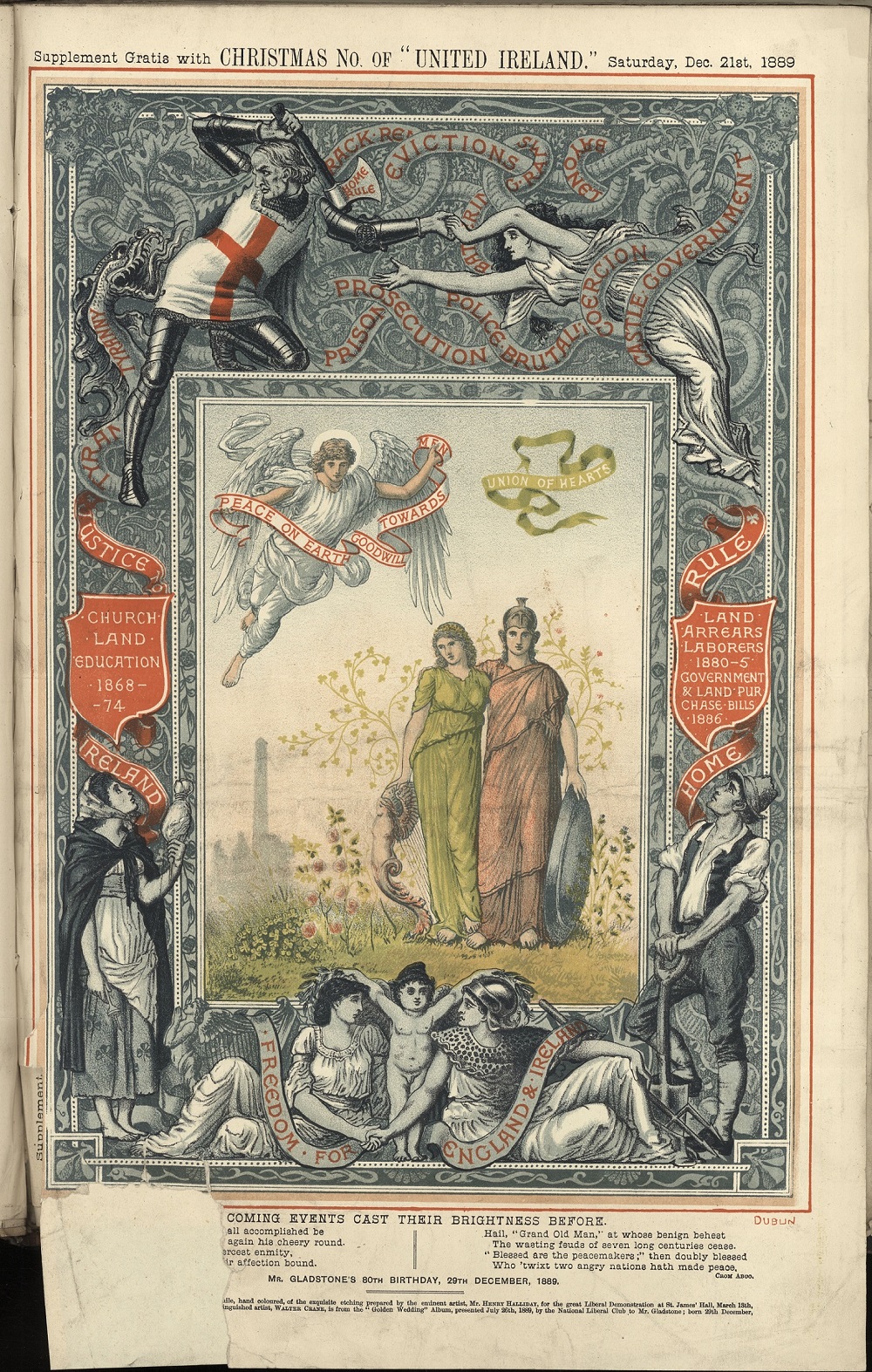

This month we are displaying a print from the 1889 Christmas edition of United Ireland. Throughout the late 19th century nationalist papers like The Freeman’s Journal and United Ireland published special Christmas issues. The accompanying picture supplements were often highly illustrative, with romanticised images from history or idealistic images of the future.

In a departure from the regular cartoonist J.D. Reigh, this detailed illustration was by the British artist Walter Crane, with a central panel by Henry Halliday. Crane’s original work had been presented to former Prime Minister William Gladstone at the Liberal Club in London for his wedding anniversary in July of that year, and United Ireland had reproduced both works to celebrate his 80th birthday in December. It served as both a decorative celebration of Gladstone’s political reforms and as a vision of the future relationship between England and Ireland.

The title “Coming events cast their brightness before” was a play on the proverb “Coming events cast their shadows before”. Though he is now more associated with his designs for children’s books, Walter Crane was an active socialist who produced idealistic political imagery for a number of left-wing British publications and organisations.

In this picture Gladstone is depicted wearing the cross of St. George. He is using his axe of Home Rule to rescue Erin from a serpent representing tyranny, coercion and a range of other political and social evils. In the centre panel Erin and Britannia walk arm in arm.

Banners on either side celebrate Gladstone’s legislative reforms since the 1860s. Kathleen Ní Houlihan and "Pat" stand underneath the banners. Erin and Britannia are depicted again underneath the centre panel, holding hands and draped in a banner that reads, “Freedom for England & Ireland”.

The picture was a strikingly optimistic one for United Ireland to include as a Christmas supplement, considering political events of the previous years. Gladstone’s attempts to pass a Home Rule Bill had brought down his own government in 1886 and caused an irreparable split in the Liberal Party. But Gladstone’s support for an Irish parliament saw him increasingly depicted in nationalist papers as a heroic figure similar to Parnell.

The Oireachtas Library’s print has slight damage to the bottom left corner, and to the first stanza of the accompanying poem, which reads as follows:

May this bright vision all accomplished be

Ere Christmas comes again his cheery round

Two nations long at fiercest enmity

At last in bonds of fair affection bound.

Detail from the print in the 1889 Christmas edition of United Ireland

References

Hollander, J. A. (2000) Heroic Construction: Parnell in Irish Political Cartoons, 1880-1891. New Hibernia Review/Irish Éireannach Nua, 4(4), 53-65

McBride, L. W. (1998) Historical Imagery in Irish Political Illustrations, 1880-1910. New Hibernia Review/Irish Éireannach Nua, 2(1), 9-25

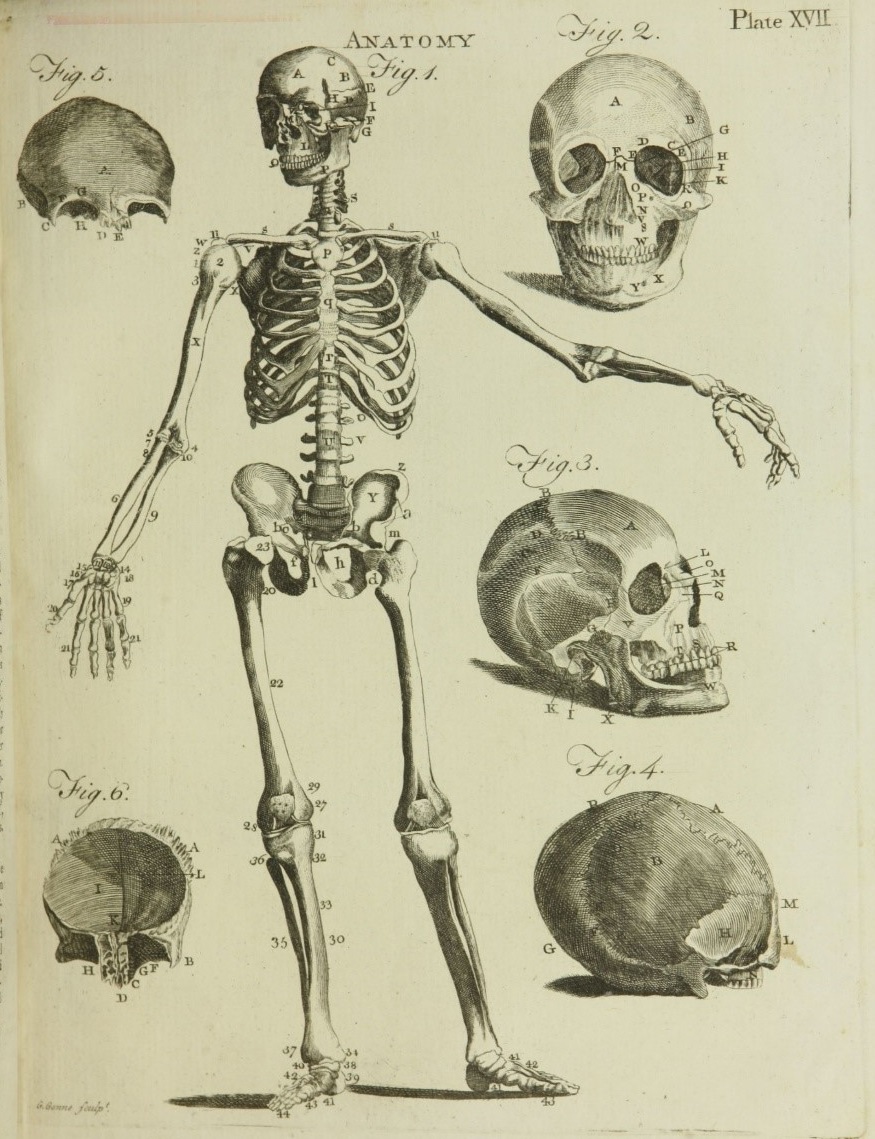

There were over 500 copperplates included in Moore’s edition of the Encyclopaedia, illustrating a selection of topics

November 2020

This month, to mark Science Week, we are exhibiting the first volume of our 3rd edition Encyclopaedia Britannica from 1790. The official edition was published in Edinburgh but the edition in the Library’s collection is a well-known pirated copy published by James Moore in Dublin.

The Encyclopaedia Britannica is the oldest English-language general encyclopaedia. It was first published in 1768. The multi-volume work laid out articles in alphabetical order on a variety of subjects from science and the arts. The content was either compiled from other publications or written especially by the editors and subject experts.

The 3rd edition of the Encyclopaedia introduced the exciting new science of aerostation, the study of aerial navigation. This section recounts a century of scientific experimentation, culminating in 1782 when two French brothers, Joseph-Michel and Jacques-Étienne Montgolfier, made a breakthrough. Taking inspiration from the rising effects of smoke, the brothers set out to create artificial ‘balloons’ of silk, linen and other materials, under which they attached little boxes. When they lit fires inside the boxes, the heated air filled the balloons and lifted them into the air.

The brothers soon found themselves demonstrating their flying machines to large audiences, and eventually to King Louis XVI and Queen Marie Antoinette. Building a decorative new balloon for the occasion, they attached a wicker basket with a live sheep, rooster and duck. These were, according to the Encyclopaedia, “the first animals ever sent through the atmosphere”. The balloon, though damaged by a gust of wind in the experiment, rose to a height of 1,440 feet, stayed suspended in the air for 8 minutes and then landed 10,200 feet away. The animals were unharmed. (Though not mentioned in the Encyclopaedia, Richard Crosbie was inspired by the Montgolfier brothers to become the first Irish aeronaut when he took to the air in a balloon over Ranelagh Gardens on 19 January 1785.)

Illustrations of early hot air balloons from Encyclopaedia Britannica, including those of the Montgolfier brothers

The Encyclopaedia Britannica became very popular in homes and educational settings, being viewed and trusted as a layman’s guide to general knowledge. But as scientific and other knowledge developed during the 19th and 20th centuries, it became difficult for editions to keep pace. Moving from a practice of publishing every 10-20 years to annual publication did little to help, as the fast turnaround meant that many subjects were left unrevised, sometimes for decades. Criticism mounted about outdated information, and particularly cultural and social biases.

The editors made several attempts to reorganise the structure of the content and experimented with new digital formats as they became available in the 1970s and 1980s. But sales declined considerably in the 1990s in competition with Microsoft’s Encarta and as the world wide web developed. Though the digital edition is still a popular subscription for schools and libraries, the final print edition was issued in 2010.

References

Auchter, D. (1999). The evolution of the Encyclopaedia Britannica: from the Macropaedia to Britannica Online. Reference Services Review, 27(3), 291-299.

Kafker, F.A. & Loveland, J. (2011). The publisher James Moore and his Dublin edition of the “Encyclopaedia Britannica”: a notable eighteenth-century Irish publication. Eighteenth-century Ireland/Iris an dá chultúr, 26, 115-139.

MacMahon, B. (2010). 'A most ingenious mechanic': Ireland's first airman. History Ireland, 18(6).

Stewart, E.D., Hardy Wise Kent, C., et al. (2020, October 20). Encyclopaedia Britannica.

www.britannica.com/topic/Encyclopaedia-Britannica-English-language-reference-work

October 2020

This month we are exhibiting John O’Connell’s Repeal Dictionary, published 175 years ago by the Loyal National Repeal Association. Though officially titled ‘Part 1’, a second part was never compiled, so the politically charged dictionary only runs from A (for Absenteeism) to M (for Murder).

Daniel O’Connell, John’s father, organised the Loyal National Repeal Association in 1840 as part of his political campaign to repeal the 1801 Act of Union and restore an Irish parliament. As a charismatic speaker and politician, O’Connell soon attracted wide public support for the cause, in Ireland and in America. However, there was growing discontent amongst a younger generation of members who came to be known as the Young Irelanders. By the time the Repeal Dictionary was published in 1845, relations between the two groups were becoming particularly fraught.

The Young Irelanders distrusted Daniel O’Connell’s attempts to ally with the Whig party in return for Irish reforms. Many worried that such compromises would at best result in a devolved parliament with limited autonomy or at worst, in no political reform at all. At the same time, the pro-Catholic stance of the O’Connells alienated the Protestant members of the group. The Young Irelanders also held that armed struggle should be an option if all political attempts failed to establish home rule. The O’Connells, however, remained firmly opposed to violence.

Another area of disagreement between the two groups was that of slavery in America. The O’Connells were staunch abolitionists. But Young Irelanders argued that speaking out against slavery could cost the nationalist movement valuable support from America. The issue was compounded during the famine years, when, in the absence of help from the newly elected Whig government, famine relief was highly reliant on private donations from abroad. Daniel O’Connell was adamant that the Association should turn down 'blood-stained money' from slave-owning or pro-slavery Americans. He lent his signature to anti-slavery petitions, spoke publicly on the matter and met with prominent abolitionists like Frederick Douglass, who visited Ireland for several months in 1845.

Renowned abolitionist Frederick Douglass (left) was impressed by the anti-slavery rhetoric of Daniel O’Connell (right) when he visited Ireland in 1845

In the end, the issues proved unresolvable. Daniel O’Connell died in 1847. John O'Connell failed to heal the divisions in the Repeal Association and the Young Irelanders broke away to form the Irish Confederation.

References

Clarke, R. (1942). The relations between O’Connell and the Young Irelanders. Irish Historical Studies, 3(9), 18-30

Delahunty, I. (2013). ‘A noble empire in the West’: Young Ireland, the United States and Slavery. Britain and the World, 6(2), 171-191

September 2020

This month we are looking at attitudes to imperialism in its collection of Irish nationalist cartoons from the 1880s.

Two imperial enterprises of note in the 19th century were the so-called "Scramble for Africa" and the "Great Game". The latter term refers loosely to the diplomatic and military confrontations between Britain and Russia in central Asia, where Britain was keen to prevent Russian interests from encroaching on India. The "Scramble for Africa" denotes the period between the 1880s and 1914 when European countries partitioned about 90% of the African continent.

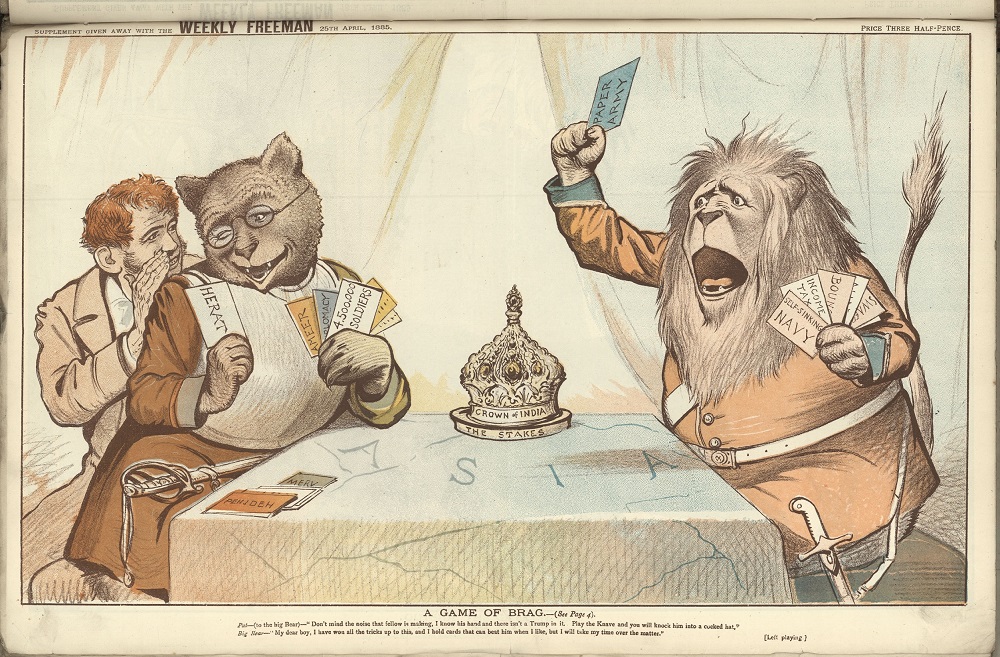

A game of brag, Weekly Freeman, 25 April 1885

Irish attitudes to imperialism in the 19th century were complex. Many Irish people served abroad in the military and civil administration of British-controlled territories. For some, there was great pride associated with being part of a mighty empire. People believed that "Western" influence could improve the lives of those in colonised nations or focussed on the benefits of expanded commercial and trade opportunities. For some Home Rule leaders, such as Isaac Butt, there was no mutual exclusivity between being an Irish nationalist and being part of the British empire. Others, such as Michael Davitt, were resolutely anti-imperialist.

Irish nationalist newspapers tracked British foreign policy intensely. When conflict broke out in colonies like Sudan and Afghanistan, newspapers followed quickly with reports, editorials and political cartoons. Attitudes were sometimes mocking of British military defeat, or revelled in the perceived weakness of Britain compared to Russia, as shown in the Weekly Freeman cartoons A game of brag and Outside the gate.

Outside the gate, Weekly Freeman, 2 May 1885

At other times, the cartoons displayed an empathy with foreign nationalists. This cartoon from the Weekly News shows Irish members of the British military reading news of unrest at home, while sympathising with Sudanese rebels as “men who are only defending their own country”.

Private McCarthy..., Weekly News, 28 February 1885

Nationalist newspapers strongly conflated the political and civil unrest of 1880s Ireland with suppression of nationalist movements in British colonies. Though there was often a sense of superiority over the peoples of Africa and Asia, the general view was that those nations should be able to decide for themselves how they were governed. Similar to the Irish cultural revival, anti-imperialist sentiment became a popular means for Irish nationalists in the late 19th century to further emphasise "difference" between Ireland and Britain.

Further reading

De Nie, M. (2012). "Speed the Mahdi!" The Irish Press and Empire during the Sudan Conflict of 1883-1885. Journal of British Studies, 51(4), 883-909.

Townend, P.A. (2016). The Road to Home Rule: Anti-Imperialism and the Irish National Movement. Madison, Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Press.

August 2020

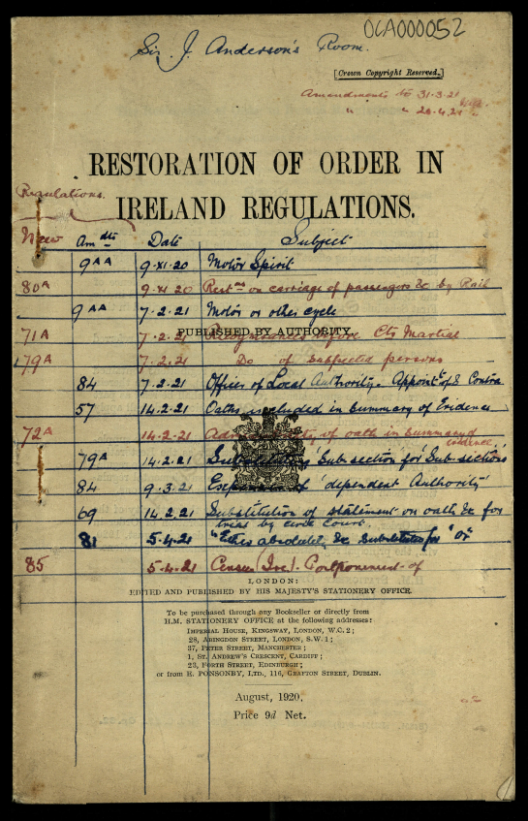

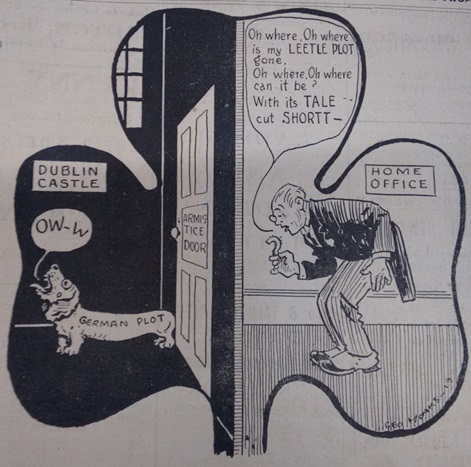

This month we mark 100 years since the passing of the Restoration of Order in Ireland Act (ROIA) by exhibiting a copy of the associated regulations. This set of regulations has handwritten amendments on the front cover and was kept in the office of Under-Secretary John Anderson at Dublin Castle.

ROIA essentially extended regulations under the Defence of the Realm Act 1914 (DORA). This wartime emergency legislation gave the government enormous social and economic control over civilians. Most controversially it allowed for the internment and court martial of civilians who acted or were planning to act in violation of national security.

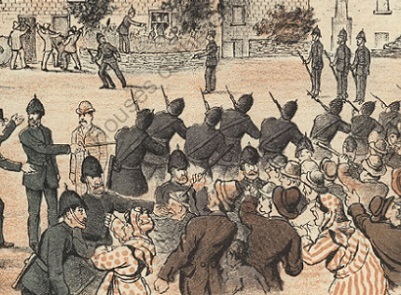

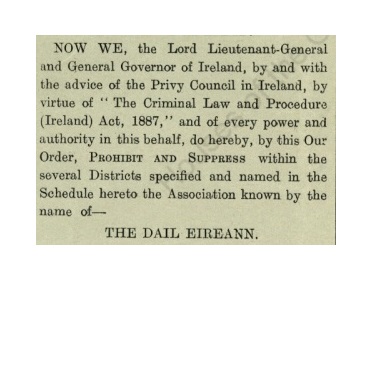

After the war the regulations continued to be enforced in Ireland to thwart an increasingly confident republican movement. Intimidation and violence saw many quit the police force. People started refusing to give evidence in cases, making it difficult to convict members of Sinn Féin or the IRA. The newly declared Dáil Éireann even established its own court system.