Learn about some of the first women to participate in parliamentary politics in Ireland. The biographies on this page are reproduced by kind permission of the Dictionary of Irish Biography and Maedhbh McNamara, co-author of Women in Parliament, Ireland 1918-2000.

Countess de Markievicz / Courtesy of the National Library of Ireland

Countess de Markievicz

Countess de Markievicz was one of the two women who stood in the general election of 1918 and the first woman elected to the British House of Commons. Like the other Sinn Féin candidates, she had pledged to abstain from the Westminster Parliament, and so she never took her seat. Instead, she joined the revolutionary Dáil Éireann, becoming the first female TD and the first female Minister in western Europe.

Markievicz, Constance Georgine (1868–1927), Countess Markievicz, republican and labour activist, was born 4 February 1868 at Buckingham Gate, London, eldest of the three daughters and two sons of Sir Henry Gore-Booth of Lissadell, Co. Sligo, philanthropist and explorer, and Georgina Mary Gore-Booth (née Hill) of Tickhill Castle, Yorkshire. She was taken to the family house at Lisadell as an infant, and retained a strong attachment to the west of Ireland despite her frequent sojourns in Dublin and abroad.

She was born into a life of privilege. Descended from seventeenth-century planters, the Gore-Booths were leading landowners who entertained lavishly at Lissadell, and enjoyed country pursuits including riding, hunting, and driving. An active and demonstrative child, she was known for her skill in the saddle and for her friendly relations with the family's tenants. She and her favourite sister, Eva, were brought up in a manner that reflected their class and social standing. They are recalled as ‘two girls in silk kimonos’ in the poem ‘In memory of Eva Gore-Booth and Con Markiewicz’ (October 1927) by W. B. Yeats. Educated at home, they were taught to appreciate music, poetry, and art, and in 1886 they were taken by their governess on a grand tour of the Continent. Constance made her formal debut into society in 1887 when she was presented to Queen Victoria at Buckingham Palace.

She hoped to study art, but faced opposition from her parents who disapproved of her ambition and refused to fund her studies. They finally relented in 1893, and she went to the Slade School of Art in London. On her return to Lissadell, she took up the cause of women's suffrage, presiding over a meeting of the Sligo Women's Suffrage Society in 1896. But she remained interested in art, and in 1898 her parents were persuaded to allow her to go to Paris to further her studies. While in Paris she met fellow art student Count Casimir Dunin-Markievicz, a Pole whose family held land in the Ukraine. They were married in London in 1900 and a daughter, Maeve, was born the following year. The couple returned to Paris in 1902, leaving their daughter in the care of Lady Gore-Booth. The family was reunited in Dublin in the following year, but from about 1908 Maeve lived almost exclusively with her grandparents at Lissadell.

Markievicz and her husband became involved in Dublin's liveliest cultural and social circles, exhibiting their paintings, producing and acting in plays at the Abbey Theatre, and helping to establish the United Arts Club. She and her husband separated amicably about 1909. Her conversion to Irish republicanism dates from about 1908 when she joined Sinn Féin and Inghinidhe na hÉireann (Daughters of Ireland). She also helped to found and became a regular contributor to Bean na hÉireann (Woman of Ireland), the first women's nationalist journal in Ireland. She continued to advocate women's suffrage, but devoted most of her time to overtly nationalist causes such as the establishment in 1909 of the Fianna Éireann, a republican youth movement. By 1911 she had become an executive member of Sinn Féin and Inghinidhe na hÉireann, and was arrested that year while protesting against the visit to Dublin of George V.

Markievicz became increasingly interested in socialism and trade unionism. She spoke in 1911 at a meeting of the newly established Women Workers' Union and remained a strong supporter. An advocate of striking workers during the lock-out of 1913, she organised soup kitchens in the Dublin slums and at Liberty Hall. Markievicz became an honorary treasurer of the Irish Citizen Army, and was instrumental in merging Inghinidhe na hÉireann with Cumann na mBan, a militant women's republican organisation which was established to support the Irish Volunteers. Fiercely opposed to Irish involvement in the British war effort, she co-founded the Irish Neutrality League in 1914, and supported the small minority who split from the larger Volunteer organisation over the issue of Irish participation in the war. She remained active in labour circles, co-founding in 1915 the Irish Workers' Co-operative Society, while also participating in the military training and mobilisation of the Citizen Army and the Fianna.

An aggressive and flamboyant speaker who enjoyed wearing military uniforms and carrying weapons, Markievicz was known for her advocacy of armed rebellion against British authority. She welcomed the Easter rising, acting as second-in-command of a troop of Citizen Army combatants at St Stephen's Green. As British troops occupied buildings surrounding the park, it became a deathtrap for the Citizen Army who were forced to seek refuge in the College of Surgeons. After a week of heavy fire, Markievicz and her fellow rebels surrendered. She was originally sentenced to death for her part in the rebellion, but this was commuted on account of her sex; she was transferred to Aylesbury prison and was released under a general amnesty in June 1917, having served fourteen months. While being held at Mountjoy prison just after her surrender, she had begun to take instruction from a Roman Catholic priest, and shortly after returning to Ireland she was formally received into the church. Notoriously ignorant of the finer points of catholic theology, she none the less embraced her new faith wholeheartedly, claiming to have experienced an epiphany while holed up in the College of Surgeons.

Markievicz threw herself behind Sinn Féin: she was elected to its executive board and was one of the many advanced nationalists arrested in 1918 on account of their alleged involvement in a treasonous ‘German plot’. During her incarceration, she was invited to stand as a Sinn Féin candidate for Dublin's St Patrick's division at the forthcoming general election. She was the first woman to be elected to the British parliament, but like all Sinn Féin MPs she refused to take her seat at Westminster. On her release and return to Ireland in March 1919, she was named minister for labour in the first Dáil Éireann, a position that bridged her commitment to labour and to the fledgling republic. Arrested again in June for making a seditious speech, she was sentenced to four months hard labour in Cork, the third time she had been incarcerated in four years. After her release Markievicz continued to defy British authorities by maintaining her work for Sinn Féin and the dáil. Such political activity became more dangerous and difficult after the outbreak of the Anglo–Irish war in early 1919 and Markievicz spent much of this time on the run and in constant danger of arrest. She was arrested again in September 1920 and sentenced to two years' hard labour after a long period on remand. Released in July 1921 in the wake of a truce agreed between the British government and Irish republicans, she returned to her ministry, but any hope of political stability was dashed by the split in republican ranks over the Anglo–Irish treaty of December 1921. Dressed in her Cumann na mBan uniform, Markievicz addressed the dáil in a characteristically theatrical fashion, condemning the treaty and reiterating her advocacy of an Irish workers' republic. Reelected president of Cumann na mBan and chief of the Fianna in 1922, she reaffirmed her opposition to the treaty through those organisations.

As an active opponent of the treaty, Markievicz refused to take her seat in the dáil and was once again forced to go into hiding while former comrades became embroiled in a civil war. She composed anti-treaty articles and continued to engage in speaking tours to publicise the republican cause. Elected to the dáil for Dublin South in August 1923, she refused to take the oath of allegiance to the king and, like other elected republicans, she thus disqualified herself from sitting. She was arrested for the last time in November 1923 while attempting to collect signatures for a petition for the release of republican prisoners, and went on hunger strike until she and her fellow prisoners were released just before Christmas. Removed from parliamentary politics and increasingly detached from her former republican colleagues – some of whom remained suspicious of female politicians and of Markievicz in particular – she remained committed to the republican ideal, producing numerous publications which focused more on former glories than on disappointing contemporary realities. She joined Fianna Fáil when it was established in 1926, finally breaking her ties with Cumann na mBan, which opposed the new political party. She stood successfully as a Fianna Fáil candidate for Dublin South at the June 1927 general election, but hard work and often rough conditions took their toll, and her health began to fail. She was admitted to Sir Patrick Dun's hospital and, declaring that she was a pauper, was placed in a public ward, where she died on 15 July 1927; she was buried in Glasnevin cemetery.

This biography is reproduced here by kind permission of the Dictionary of Irish Biography.

Winifred Carney / Courtesy of Kilmainham Gaol Museum KMGLM 2012.0243

Winifred Carney

Winifred Carney was one of the two women who stood in the 1918 general election. She stood in a unionist division of Belfast, and was not elected. A member of the Irish Citizen Army, she was a close friend and secretary to James Connolly. She was in the GPO during Easter 1916 and was interned after the Rising. She continued to work for the trade union and labour movements and was critical of the social conservatism of Irish Governments after independence.

Carney, Winifred (‘Winnie’) (1887–1943), trade unionist, feminist, and republican, was born Maria Winifred Carney 4 December 1887 at Fisher's Hill, Bangor, Co. Down, youngest child among three sons and three daughters of Alfred Carney, commercial traveller, and Sarah Carney (née Cassidy; d. 1933). Her father was a protestant and her mother a catholic; the children were reared as catholics. After her birth her parents moved to Belfast and separated during her childhood. Her father went to London and little more was heard from him; her mother supported the family by running a sweetshop on the Falls Road. Winifred was educated at the CBS in Donegall St., Belfast, where she became a junior teacher. Independently minded, she later worked as a clerk in a solicitor's office, having qualified as shorthand typist from Hughes's Commercial Academy. In her early twenties she became involved in the Gaelic League and the suffragist and socialist movements. She had a wide range of cultural interests in literature, art, and music, had a good voice, and played the piano well.

In 1912 she took over from her friend Marie Johnson as secretary of the Irish Textile Workers' Union based at 50 York St., Belfast, which functioned as the women's section of the ITGWU and was led by James Connolly. Her pay was low and irregular but she and her colleague Ellen Grimley worked with great enthusiasm to improve the wages and conditions of the mill-girls, and Carney managed the time-consuming and tedious insurance section of the union. During the 1913 lockout she was active in fund-raising and relief efforts for the Dublin workers. Many of those connected with the ITGWU were drawn into the republican movement and she was present at the founding of Cumann na mBan in Wynn's Hotel, Dublin (2 April 1914). A close friend of Connolly, she joined the Citizen Army (she was a crack shot with a rifle), and became his personal secretary. She appears to have been completely in his confidence and in full agreement with his revolutionary aims. On 14 April 1916 he summoned her to Dublin to assist in the final preparations for the Easter rising, and for the next week she typed dispatches and mobilisation orders in Liberty Hall. She was the only woman in the column that seized the GPO on Easter Monday, 24 April (although several others arrived later). During the rising she acted as Connolly's secretary and, even after most of the women had been evacuated from the GPO, she refused to leave and replied sharply to Patrick Pearse when he suggested she should. She stayed with Connolly in the makeshift headquarters at 16 Moore St., typing dispatches and dressing his wound, and attending to the other wounded men. After the surrender (29 April) she was interned, first in Mountjoy and from July in Aylesbury prison, and was released 24 December 1916. In autumn 1917 she was Belfast delegate to the Cumann na mBan convention, and was appointed president of the Belfast branch. In 1918 she was briefly imprisoned in Armagh and Lewes prisons. She stood for Sinn Féin in Belfast's Victoria division in the general election of 1918 (the only woman candidate in Ireland apart from Constance Markievicz, ), advocating a workers' republic, but she polled badly, winning only 4 per cent of the votes. Afterwards she was very critical of the support she had received from Sinn Féin. In 1919 she was transferred to the Dublin head office of the ITGWU, but did not get on well with colleagues such as Joe McGrath and William O'Brien and returned to Belfast after a few months. She was Belfast secretary of the Irish Republican Prisoners' Dependents Fund (1920–22). She became a member of the revived Socialist Party of Ireland in 1920 and attended the annual convention of the Independent Labour Party in Glasgow in April 1920.

Never deviating in her hope for the establishment of Connolly's workers' republic, she opposed the treaty, and sheltered republicans such as Markievicz and Austin Stack in her home at 2a Carlisle Circus, Belfast. On 25 July 1922 she was arrested by the RUC and held in custody for eighteen days after ‘seditious papers’ were discovered in her home. She refused to recognise the court and was fined £2. She was critical of partition and the social conservatism of Irish governments after independence and remained in Belfast, concentrating on helping the local labour movement. She refused to accept a pension for her part in 1916, relenting only weeks before her death. In 1924 she joined the Court Ward branch of the Northern Ireland Labour Party and was active in the party's radical wing promoting republican socialism. In discussions with colleagues she always praised Connolly and defended the 1916 rising, but was modest about her own part in it and never revealed what she knew of its planning; she also shared Connolly's distrust of James Larkin. Some regarded her as rather austere and sharp-tongued, but close friends spoke of her kindness and charm, and praised her strong personal and political loyalties. She continued to work for the ITGWU in Belfast and Dublin until September 1928, when she married George McBride. McBride (1898–1988), a protestant, was a textile engineer, staunch socialist, and NILP member, who had joined the UVF in 1913 and fought in the British army (1914–18). They lived at 3 Whitewell Parade, Whitehouse, Belfast, and, despite their disagreements about Irish nationalism, their marriage was very happy; they had no children. In about 1934 Carney joined the small Belfast Socialist Party, but her health was deteriorating and she took little active part in politics. She died 21 November 1943 in Belfast and was buried in Milltown cemetery, Belfast.

This biography is reproduced here by kind permission of the Dictionary of Irish Biography.

Ada English in Gaelic costume / By kind permission of Gill

English, Adeline (‘Ada’) (1875–1944), doctor, academic, and nationalist, was born 10 January 1875 in Caherciveen, Co. Kerry, younger daughter of Patrick English, pharmaceutical chemist, and Nora English (née McCardle). She was reared in Mullingar, Co. Westmeath, though her father may have later been employed by Ballinasloe asylum, as her address on matriculation (1895) is given as the asylum. Educated at the local Loreto Convent and at university classes in Lower Merrion St., Dublin, she graduated from the Royal University of Ireland in Dublin, where she was one of the earliest women students at the school of medicine in Cecilia Street. While in Dublin she became interested in the Gaelic League, and attended Irish classes given by her friend Patrick Pearse, becoming a fluent speaker. On graduating MB, B.Ch., and BAO in 1903, she briefly worked as house surgeon in the Children's Hospital, Temple St., as clinical assistant in Richmond Asylum, and in the Mater Hospital, Dublin, before accepting a post as assistant medical officer to Ballinasloe and Castlerea mental asylums. She subsequently became involved with the Ballinasloe branch of the Women's National Health Association, serving as its honorary secretary for a short time, and in 1914 was appointed as the first statutory lecturer in mental diseases at UCG.

In the years preceding the 1916 rising she became politically active, joining the Ballinasloe branch of Sinn Féin on its foundation in 1910. She served as medical officer to the Irish Volunteers from their inception, and later joined Cumann na mBan, holding a seat on their executive for many years. In 1921 she was tried and convicted at Renmore barracks for possession of Cumann na mBan literature. Though sentenced to nine months in prison, she was released from Galway jail after six months, having contracted ptomaine poisoning. That year she was returned to the dáil as a Sinn Féin representative for the NUI, and, like the rest of the women TDs, opposed the treaty. Her dáil career proved brief. She lost her seat the following year, but shortly after her electoral defeat joined Cathal Brugha in his occupation of the Hammam Hotel in Upper O'Connell St. during the civil war. Thereafter she concentrated primarily on her career, though she did actively campaign for the use of Irish manufactured goods in Irish institutions.

Throughout her lengthy association with the Ballinasloe asylum she did much to bring in the changes that transformed it into an up-to-date mental hospital. She was particularly active in introducing occupational therapy to the hospital; her commitment to the institution, and specifically to her patients, resulted in her turning down an offer of the post of resident medical superintendent (RMS) at Sligo mental hospital in 1921. For a time she was involved in the drama group that was formed in the hospital. Appointed RMS to Ballinasloe by 1941, she retired from her post at UCG in 1943, and died 27 January 1944 in Ballinasloe. At her express wish she was buried alongside her former patients in nearby Creagh cemetery.

This biography is reproduced here by kind permission of the Dictionary of Irish Biography.

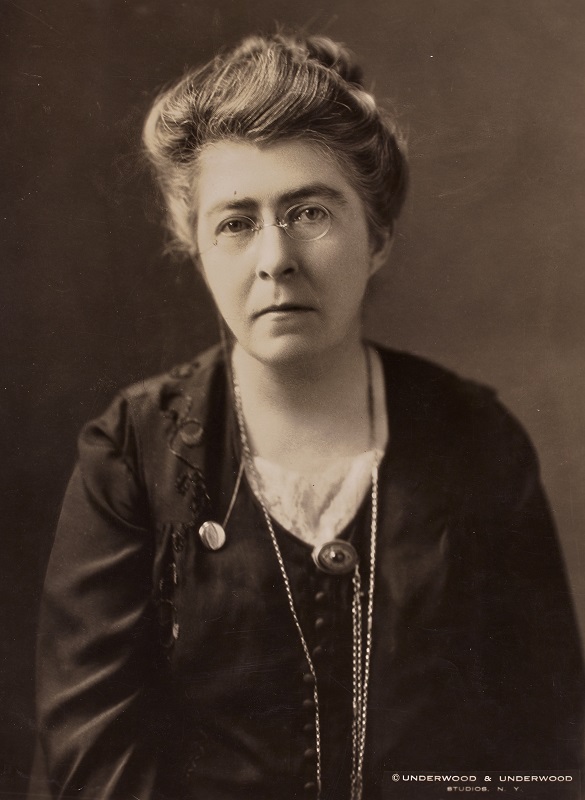

Hanna Sheehy Skeffington / Courtesy of the National Library of Ireland

Hanna Sheehy Skeffington

Hanna Sheehy Skeffington was one of the co-founders of the Irish Women's Franchise League. She was imprisoned and dismissed from her job as a result of her militant campaigning for the vote. After 1918, she remained remained active in politics and feminism for decades, and campaigned against the 1937 Constitution. She stood unsuccessfully in the 1943 general election.

Skeffington, (Johanna) Hanna Sheehy- (1877–1946), political activist, was born 24 May 1877 in Kanturk, Co. Cork, eldest among two sons and four daughters of David Sheehy, millowner and later nationalist MP, and Elizabeth (‘Bessie’) Sheehy (née McCoy), both of Co. Limerick. The family, having lived in Co. Cork and Co. Tipperary, moved to Dublin in 1887. Hanna was educated at the Dominican Convent, Eccles St., Dublin, where she won a number of prizes and exhibitions and showed a flair for languages. The threat of incipient tuberculosis in 1895 interrupted her studies and she travelled to France and Germany as a strategy for recovery. Later that year she won a scholarship to St Mary's University College, run by the Dominican order, and in 1899 graduated from the Royal University of Ireland with an honours BA in modern languages. She was awarded an MA in 1902. After graduation Hanna was employed on a part-time basis with the Dominicans in Eccles St.

Hanna met her future husband Francis (‘Frank’) Skeffington, the only child of Joseph Bartholomew Skeffington, inspector in the national schools system, and Rose Skeffington, in 1896. When the couple married (1903) they took each other's surnames as a symbol of the equality of their relationship. While Hanna was politically aware and had been one of the founders (1902) of the Women Graduates’ and Candidate Graduates' Association, established to promote the advancement of women in university education, she claimed that it was Frank who was responsible for her ardent commitment to the women's movement. Their son, and only child, Owen, was born in 1908. The couple were committed to many causes, particularly feminism, pacifism, socialism, and nationalism.

In 1902 Hanna joined the long-established Irishwomen's Suffrage and Local Government Association, which campaigned for women's access to the franchise through the genteel methods of lobbying politicians and holding meetings. The formation in London in 1903 of the militant suffrage organisation, the Women's Social and Political Union, revitalised the suffrage campaign. Hanna was aware of the activities of the WSPU and in 1908, with Gretta (Margaret) Cousins and two other women, organised the Irish Women's Franchise League, an independent, non-aligned, and militant group. By 1912 the IWFL claimed a membership of over 1,000, making it the largest suffrage group in Ireland. Hanna was a strong nationalist but did not join either Inghinidhe na hÉireann on its formation in 1900 or Cumann na mBan in 1914. She believed that women involved in nationalist organisations played a subordinate role to men (an issue much debated in the period), and that it was only through the acquisition of the vote that true citizenship would be attained.

In May 1912 the first issue of the suffrage paper The Irish Citizen, edited by Frank Sheehy Skeffington and James Cousins, appeared. When the Cousinses left for India in 1913, the Sheehy Skeffingtons took over the management of the paper, and after Frank's murder in 1916 Hanna edited the paper, intermittently, until 1920. The socialist thought of James Connolly greatly influenced her thinking and she assisted in Liberty Hall during the 1913 Dublin lock-out. The failure of the Irish parliamentary party to support women's suffrage led to the first militant suffrage activity in Ireland. On 13 June 1912 a number of women of the IWFL, including Hanna, broke some windows in government buildings. The women were arrested and imprisoned for a month. In prison they immediately and successfully lobbied for political status. The treatment of two English suffragettes by the Irish authorities led Hanna and a number of other suffragettes to go on hunger strike, a strategy they were to continue whenever they were imprisoned. Because of her feminist activities Hanna was sacked from her German teaching post at the Rathmines School of Commerce. She now devoted more time to suffrage and to her work on the Irish Citizen, corresponding with suffragists in England and the United States. Hanna and Frank took a strong pacifist position in relation to the growing militarism of the time. On the outbreak of the 1916 rising Frank was involved in organising anti-looting bands. He was arrested and shot without trial on the orders of Capt. J. C. Bowen-Colthurst (qv), a British army officer. Hanna was thrown into personal and emotional turmoil by that event. An inquiry into the murder left too many questions unanswered for her satisfaction. She refused all offers of compensation from the government and decided to bring the facts of the case before the American public. At the invitation of the friends of Irish Freedom Hanna toured the USA from October 1916 to August 1918, speaking at over 250 meetings; this was the first of four American tours. Her major speech from her first tour, British militarism as I have known it, was published in New York in pamphlet form in 1917.

In late 1919 Hanna was elected as a Sinn Féin candidate to Dublin corporation, and when a truce was declared in July 1921 she was the director of organisation for Sinn Féin. She was also on the executive committee of the Irish White Cross, a relief organisation funded by the American Committee for Relief in Ireland. She opposed the Anglo–Irish treaty and in 1922–3 accompanied Linda Kearns (Linda MacWhinney) and Kathleen Boland to the USA on a fund-raising trip for the relief of the families of Irish republican soldiers held as prisoners in the Irish Free State. Hanna was also a member of the Prisoners' Defence Association and helped form the Women Prisoners' Defence League in 1922. In August 1923 she was sent to Paris by Éamon de Valera, in an unsuccessful attempt to put the case to the League of Nations against the recognition of the Irish Free State.

Hanna was also a member of the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom, a pacifist organisation, of which she later became a vice-president. In May 1926 she was one of four women appointed to the executive of the new Fianna Fáil party. But when de Valera entered the dáil she split with the party. While she was politically disturbed by the nature of Irish government during the 1920s and 1930s, she remained an active feminist. During these years she supported herself and Owen though her journalism, writing extensively for the Irish World, and gave many public talks and lectures. In 1926 she led protests against the staging of Sean O'Casey's The Plough and the Stars at the Abbey theatre, claiming that it derided the men and women who had taken part in the 1916 rising.

In August 1930 Hanna went as a delegate of the Friends of Soviet Russia to study the Soviet system of government and, like many of her contemporaries, she remained an active sympathiser with the communist system. She contributed to, and later became assistant editor of, An Phoblacht and its successor Republican File. In January 1933 she was arrested and imprisoned after a public speech in Newry, having defied an exclusion order that had been imposed on her by the Northern Ireland government. She opposed the 1937 constitution and, through the Women Graduates' Association, campaigned publicly against its provisions. In November 1937, as a consequence of misgivings about the new constitution, Hanna was instrumental in establishing the Women's Social and Progressive League as a women's political party that declared itself to be non-sectarian and non-party. She stood unsuccessfully as a candidate for the party in the 1943 general election. Her health deteriorated in 1945 and she died of heart failure on 20 April 1946 and was buried beside her husband Frank in Glasnevin cemetery in Dublin.

The most extensive collection of papers, including photographs, relevant to Hanna Sheehy Skeffington is to be found in the Sheehy Skeffington papers, housed in the NLI. There is some correspondence from her, dating from 1926, in the Fianna Fáil party archives, Dublin. Her correspondence with Alice Parks is in the Alice Parks collection, box no. 19, Hoover Institution Archives, Stanford, California.

This biography is reproduced here by kind permission of the Dictionary of Irish Biography.

Dr. Kathleen Lynn / Reproduced by kind permission of the Royal College of Physicians of Ireland

Dr. Kathleen Lynn

Dr. Kathleen Lynn was elected to the fourth Dáil in 1923, but did not take her seat as she opposed the Treaty. She was one of the first women to obtain a medical degree from the Royal University of Ireland and founded a children's hospital. She joined the suffrage movement and was a medical attendant to feminist hunger strikers from 1912. During the 1916 Rising she was chief medical officer of the Irish Citizen Army.

Lynn, Kathleen (1874–1955), medical practitioner and political activist, was born 28 January 1874 in Mullafarry, near Cong, Co. Mayo, second oldest of three daughters and one son of Robert Lynn, Church of Ireland clergyman, and Catherine Lynn (née Wynne) of Drumcliffe, Co. Sligo. Despite aristocratic relations and a comfortable upbringing, her professional career was primarily concerned with the less well-off. Lynn's Mayo childhood, where poverty coincided with land agitation, may have motivated her to seek political and pragmatic solutions to socio-economic deprivation. After education in Manchester and Düsseldorf, she attended Alexandra College, Dublin. She graduated from Cecilia Street (the Catholic University medical school) in 1899, and, after postgraduate work in the United States, became a fellow of the Royal College of Surgeons in 1909. She was refused a position in the Adelaide Hospital because of her gender, and eventually joined the staff of Sir Patrick Dun's Hospital. Valuable experience was also gained at the Rotunda Lying-In Hospital. From 1910 to 1916 she was a clinical assistant in the Royal Victoria Eye and Ear Hospital, the first female resident doctor at the hospital, but was not allowed to return after the 1916 rising. Her private practice, at 9 Belgrave Road, Rathmines, was her home between 1903 and 1955.

An active suffragist and an enthusiastic nationalist, Lynn was greatly influenced by labour activists Helena Molony, Constance Markievicz, and James Connolly. Her work in the soup kitchens brought her into close contact with impoverished families in Dublin during the 1913 lock-out of workers. She joined the Irish Citizen Army and taught first-aid to Cumann na mBan. As chief medical officer of the ICA during the 1916 rising, she tended to the wounded from her post at City Hall, and her car was used for the transportation of arms and for Markievicz to sleep in. Imprisoned in Kilmainham, with her close friends Helena Molony and Madeleine ffrench-Mullen, she complained bitterly about the cramped prison conditions. A committed socialist, she was an honorary vice-president of the Irish Women Workers' Union in 1917 and denounced the poor working conditions of many women workers. She was vice-president of the Sinn Féin executive in 1917, and her home was a meeting point for fellow Sinn Féin women, notably for meetings of Cumann na dTeachtaire (the league of women delegates). On the run between May and October 1918, she was sent to Arbour Hill detention barracks when arrested. The authorities agreed to release her, on the intervention of the lord mayor of Dublin, Laurence O'Neill, as her professional services were essential during the 1918–19 influenza epidemic. Despite her high political profile, Lynn is remembered, primarily, for her work in St Ultan's Hospital for Infants on Charlemont St., which she established in 1919 with her confidante, Madeleine ffrench-Mullen. Its philosophy was to provide much-needed facilities, both medical and educational, for impoverished infants and their mothers.

Though she was active in south Tipperary during the war of independence, Lynn's national prominence faded after the heady 1913–23 period. In 1923 she was elected to Dáil Éireann as Sinn Féin candidate for Dublin county on the anti-treaty side, but did not take her seat. She failed to retain her seat in the June 1927 election but was an active member of Rathmines urban district council between 1920 and 1930. She commented regularly on public-health matters such as housing and disease prevention. As council member of the Irish White Cross she endeavoured to help republicans and was very critical of the newly formed Irish Free State's attitude to anti-treatyites. At St Ultan's, Lynn fostered international research on tuberculosis eradication. In 1937, through the efforts of her colleague Dorothy Stopford-Price, the hospital introduced BCG (Bacillus Calmette-Guerin) inoculation, which prevented TB. She also encouraged links with US and continental medical practitioners. Ffrench-Mullen and Lynn visited the United States in 1925 to raise funds for St Ultan's and visit paediatric institutions. Lynn's interest in child-centred education was furthered in 1934 when Dr Maria Montessori visited St Ultan's.

Throughout her life Lynn preached the virtues of cleanliness and fresh air. She was involved with An Óige (a youth organisation) and gave them her cottage in Glenmalure, Co. Wicklow (which she had previously lent to Dorothy Macardle for the writing of The Irish republic). Lynn's friend, the architect Michael Scott, designed a balcony outside her bedroom, where she slept for most of the year. A devout member of the Church of Ireland, she worshipped regularly at Holy Trinity church, Rathmines, but often criticised the Christian churches for losing sight of Christ's original teaching. After World War II, she was vice-chairman of the Save the German Children Society. She died on 14 September 1955 at St Mary's Nursing Home in Dublin and was given a full military funeral. Remembered primarily for her socio-political activism, she was part of a generation of women who were politicised in the 1910s and who devoted their later careers to maternal feminism. A portrait by Lily Williams is in the Royal College of Physicians, Ireland.

This biography is reproduced here by kind permission of the Dictionary of Irish Biography.

Mary MacSwiney / National Photo Company Collection, Library of Congress

Mary MacSwiney

Mary MacSwiney was a Dáil Member from the second Dáil in 1921 to 1927. She was a member of the Munster Women's Franchise League, but in 1914 she resigned and founded a branch of Cumann na mBan. She was arrested after the 1916 Rising and lost her job as a teacher, but went on to establish her own school. She voted against the Treaty and abstained from taking her seat in the Dáil after the split that followed.

MacSwiney, Mary (1872–1942), republican, was born 27 March 1872 at Bermondsey, London, eldest of seven surviving children of an English mother and an Irish émigré father, and grew up in London until she was seven. Her father, John MacSwiney, was born c.1835 on a farm at Kilmurray, near Crookstown, Co. Cork, while her mother Mary Wilkinson was English and otherwise remains obscure; they married in a catholic church in Southwark in 1871. After the family moved to Cork city (1879), her father started a snuff and tobacco business, and in the same year Mary's brother Terence MacSwiney was born. After his business failed, her father emigrated alone to Australia in 1885, and died at Melbourne in 1895. Nonetheless, before he emigrated he inculcated in all his children his own fervent separatism, which proved to be a formidable legacy.

Mary was beset by ill health in childhood, her misfortune culminating with the amputation of an infected foot. As a result, it was at the late age of 20 that she finished her education at St Angela's Ursuline convent school in 1892. By 1900 she was teaching in English convent schools at Hillside, Farnborough, and at Ventnor, Isle of Wight. Her mother's death in 1904 led to her return to Cork to head the household, and she secured a teaching post back at St Angela's. In 1912 her education was completed with a BA from UCC.

The MacSwiney household of this era was an intensely separatist household. Avidly reading the newspapers of Arthur Griffith , they nevertheless rejected Griffith's dual monarchy policy. Dramatic, Gaelic League, and separatist circles were Terence's main outlets. But women's suffrage was the cause with which Mary MacSwiney was first publicly associated. A founder member together with unionists Violet Martin and Edith Somerville of the non-militant Munster Women's Franchise League (MWFL) in 1911, MacSwiney explained to a Griffithite friend who criticised her for seeking a concession from the Westminster parliament that she sought votes for women as a matter of justice.

It was the third home rule crisis that brought about a change of her focus. After Terence MacSwiney and Tomás MacCurtain founded a Cork branch of the Irish Volunteers in 1914, Mary founded a Cumann na mBan branch at their request and withdrew from the MWFL. Dispatched to west Cork by Terence shortly before Easter 1916 to deliver a message to Sean O'Hegarty (IRB county centre), Mary returned to Cork city in Easter week to witness the disarray of the Volunteers. Among the arrested Volunteer leaders was Terence. Her return to teaching duties at St Angela's later in Easter week was shattered when the RIC arrested her in class, which led to her dismissal. That was to lead her to found her own school. But in the first instance it facilitated her campaign for Terence's welfare at a tense time in the immediate aftermath of the 1916 leaders’ executions. That took her to Dublin Castle, to the authorities in London, and to William O'Brien , MP, in the house of commons itself.

In September 1916 her sister Annie and herself opened Scoil Íte (1916–54) in their home, 4 Belgrave Place, Cork. Like Scoil Bhríde, set up by Louise Gavan Duffy in Dublin on the model of St Enda's, founded by Patrick Pearse , Scoil Íte was an Irish-Ireland school and a progressive educational establishment as well. Ex-home ruler J. J. Horgan and pro-treaty Professor Alfred O'Rahilly were among her later political opponents who nonetheless freely acknowledged MacSwiney's credentials as a progressive Irish-Ireland educationist.

In 1917 her election to Cumann na mBan's national executive, amid the movement's reorganisation, marked her ascent to her first leadership role at national level. But it was her brother's hunger strike and death in 1920, two years after his election as a TD for Cork and months after his election as Cork's lord mayor, that propelled her to national prominence. Together with Annie and Terence's wife Muriel , her vigil at Brixton prison was a key part of the hunger strike's drama, played out in front of the world's press. After his death (25 October 1920) at the end of a seventy-four-day ordeal, she assumed a large part of her brother's heroic mantle. During early 1921 she made a highly successful seven-month coast-to-coast propaganda tour of the US. In June 1921 she was elected to the dáil for Cork city.

It was her contributions in opposition to the proposed settlement in the treaty debates that made her name as an uncompromising Irish republican. At two hours forty minutes, her speech in the dáil on 21 December 1921 was the longest speech of the treaty debates, a tirade against compromise. Her opposition even led her to endorse IRA threats against pro-treaty TDs. Apocalyptically, she said the very stones would rise up if this compromise were passed. After the final majority vote in favour of the treaty, her rejection of the dáil's vote in the chamber itself was utterly contemptuous. Though she emerged from the treaty debates with a reputation for being one of the leading extremists, nevertheless she had been prepared, like Cathal Brugha and Austin Stack , in the interests of unity to accept the compromise proposed by Éamon de Valera , Document No. 2.

After re-election in June 1922 followed by abstention from the dáil, MacSwiney fought the civil war in a political, auxiliary, non-combatant role. Her success in twice embarrassing the government into releasing her from prison, after she went on hunger strike in November 1922 and April 1923 (the former a twenty-four-day hunger strike), represented her main contributions to the republican campaign.

Re-elected in August 1923, MacSwiney, Count Plunkett , and other abstentionists were stymied by de Valera's lieutenants P. J. Ruttledge and Seán T. O'Kelly during de Valera's imprisonment from August 1923 to July 1924, in their attempt to develop a fully fledged policy of abstentionism. Even so, they maintained the claims of the second dáil and of the republican government that had been set up in November 1922.

After de Valera's motion to enter the dáil if the oath were repealed was defeated at an extraordinary Sinn Féin ard fheis in March 1926, MacSwiney naively expected de Valera would have to accept the will of the majority. Despite a joint message of unity to supporters in the US at the end, never were MacSwiney and de Valera united again. After the loss of her seat in the June 1927 election, when Fianna Fáil won forty-four seats, MacSwiney and Sinn Féin never were serious players again, only a threat to stability – but a threat that could never be discounted. In 1927 it was not unexpected that she condemned Fianna Fáil when they entered the dáil and took the oath. Yet she also hoped they might still be faithful to the republic, but feared they might eventually ‘imprison and murder republicans’ (19 Dec. 1927, NLI MS 15,989).

During the late twenties, her efforts to reinvigorate the movement foundered: the self-styled second dáil was without a president from 1927 and a new forum in 1929, Comhairle na Poblachta, was stillborn. At the change of government in 1932, her considerable reservations at Fianna Fáil's taking power were balanced by her delight in the defeat of what she termed the ‘murder gang’, i.e. Cumann na nGaedheal (Connaught Sentinel, 10 Mar. 1932). Together with the movement's manifest weakness and divisiveness, that change of government changed her own representation of her role and contribution to the movement. She now referred to herself and her allies merely as ‘guardians of the republican position’ (8 June 1932; MacSwiney papers, UCD, P48a/58(20)). Even so, her efforts to reunite the movement were just as unavailing as before, and indeed she could not prevent further fragmentation and disarray. In 1933, in opposition to the movement's leftward drift, she resigned from Cumann na mBan, founding the purist Mná na Poblachta instead. After the election of Fr Michael O'Flanagan as president of Sinn Féin in 1933, when he was a Free State civil servant, MacSwiney resigned from the party in 1934.

The fragmentation and increasing marginalisation of these years culminated in a sudden crisis that proved to be the watershed event of the last years of her life. After the IRA's killing of the 73-year-old retired vice-admiral Boyle Somerville and an alleged informer John Egan, the government's ‘coercion’ of the IRA in 1936 led her to break with Fianna Fáil and throw in her lot with the IRA. De Valera unambiguously condemned the IRA for both these killings, but MacSwiney equivocated: ‘if any man was shot by the IRA he was shot for being a spy’ (Irish Independent, 6 Aug. 1936). Two years later, in 1938, she was among the members of the second dáil who transferred their powers to the IRA in response to a request by the IRA chief of staff to give moral legitimacy to a bombing campaign in England. After a heart attack in 1939, Mary MacSwiney died 8 March 1942 aged 69. De Valera offered to attend her funeral, but Annie MacSwiney contemptuously refused the offer.

By the 1930s Mary MacSwiney was widely represented as the Free State's gorgon republican – and yet even this did not give the full measure of her distinctions and achievements. Had she not risen from the ranks of the suffragists and of the first generation of newly enfranchised women to become one of the leading women in the Free State's politics? Had her credentials as a progressive Irish-Ireland educationist in her own school not been recognised by friend and foe alike? By contrast, her contribution to the republican leadership did little to avert the movement's disarray and fractiousness, and its failure to re-establish the republic. Nothing ever said of her whole approach, which shaped her contribution to these outcomes, matched the incisiveness of de Valera's telling counsel to her at the civil war's height, namely that there was a ‘difference between desiring a thing and having a feasible programme for securing it’ (Hopkinson, 188).

This biography is reproduced here by kind permission of the Dictionary of Irish Biography.

Kathleen O'Callaghan / Courtesy of the National Library of Ireland

Kate (Kathleen) O'Callaghan

Kathleen O'Callaghan came from a republican family and was a Member of the second Dáil of 1921. She was returned to the third Dáil in 1922 but, as an anti-Treaty candidate, refused to take her seat. Although she retired from active politics, she opposed the 1937 Constitution of Ireland.

O'Callaghan, Kate (Kathleen) (1885–1961), teacher and politician, was born 11 October 1885 in Crossmahon, Lissarda, Co. Cork, daughter of Cornelius Murphy, farmer. Educated at St Mary's Dominican College, Dublin, she obtained a BA from the RUI and a diploma in education from Cambridge University. In 1912 she moved to Limerick, where she succeeded her sister, Mary O'Donovan, as senior lecturer in education at Mary Immaculate College of Education, a position she held until 1914, when she was replaced by another sister, Eilis Murphy. On 30 July 1914 she married Michael O'Callaghan, who served as mayor of Limerick in 1920 and who was shot dead at his home on 7 March 1921, probably by members of the Black and Tans or Auxiliary Division of the RIC. His successor as mayor of Limerick, George Clancy, and a Volunteer, Joseph O'Donoghue, were also killed the same night. Mrs O'Callaghan refused to attend the military inquiry into their deaths, believing it to be a farce; she wrote back to say that she would only appear at an inquest conducted by her own countrymen.

Elected unopposed to Dáil Éireann as Sinn Féin candidate for Limerick City–Limerick East in 1921, she was one of six women TDs in the second dáil, all of whom voted against the Anglo–Irish treaty. In her speech against the treaty, delivered on 20 December 1921, she stated that she had been a separatist since girlhood and wanted to see an independent Ireland, outside the British empire. Reelected as a republican candidate for Limerick City–Limerick East in 1922, she was a member of the anti-treaty council of state formed by Éamon de Valera in late 1922. De Valera wanted her to undertake propaganda work in Australia in 1923, but she was arrested and imprisoned in Kilmainham jail, where she joined a republican hunger strike. Defeated as a republican candidate in the Limerick constituency in 1923, she retired from active involvement in politics. She returned to Mary Immaculate College (1924–8) as part-time supervisor of student teaching practice in schools in Limerick city.

A suffragist and supporter of women's rights, in the dáil she opposed the demotion of the labour ministry, under Countess Markievicz, from the status of a cabinet post. In 1937 she opposed the new constitution, principally on the grounds that it was based on the ‘acceptance of the British crown and membership of the British group of nations’, but also because she felt the articles relating to women were ‘a betrayal of the 1916 promise of “Equal rights and equal opportunities guaranteed to all citizens” ’ and posed ‘a grave threat to the future position of women’ (Ward (1995), 166).

A fluent Irish-speaker and a member of the Gaelic League, in later life she was very active in cultural circles in Limerick, as a founder member of Féile Luimní and chairperson of its drama section, and a member of Thomond Archaeological Society. She had no children and lived at St Margaret's, O'Callaghan's Strand, Limerick. She died 16 March 1961 in Limerick, leaving an estate of £22,767.

This biography is reproduced here by kind permission of the Dictionary of Irish Biography.

Margaret Pearse / Courtesy of Dublin City Library & Archive

Margaret Pearse

As the mother of Patrick and William Pearse, who were executed after the 1916 Rising, Margaret Pearse was regarded as a figurehead in Irish nationalism. She was a Member of the second Dáil of 1921 and opposed the Treaty.

Pearse (Brady), Margaret (1857–1932), nationalist and dáil deputy, was born in Dublin, the daughter of Patrick Brady, coal merchant, and his wife, Brigid Brady (née Savage) of Oldtown, Co. Dublin. Educated by the Sisters of St Vincent de Paul, she worked in a stationer's shop until she became the second wife of James Pearse, monumental sculptor, on 24 October 1877. They had four children: Margaret, Patrick, William and Mary Brigid. Of a strong nationalist background, she imbued her children with her firmly held beliefs. On the death of her husband, she managed, with the help of her sons, to continue his monumental sculpture business in Great Brunswick (latterly Pearse) Street. In 1908 she joined her sons and daughters at St Enda's school, taking charge of the domestic arrangements at the school. She was remembered affectionately by many of the pupils.

Aware of her sons’ intentions, she fully supported them as they left St Enda's at Easter 1916, sewing medals onto the clothes of the St Enda's boys before they marched to the GPO. Following the execution of her two sons, she adopted their cause wholeheartedly and saw it as her purpose to perpetuate their memory and do as she thought they would have done. She envisaged St Enda's as their lasting monument and reopened the college in the autumn of 1916 at Cullenswood House, Rathmines. With the help of American aid she bought the Hermitage in 1920. She toured the United States in 1924 and raised a further $10,000. The school, however, declined and she resented the interference of the fund-raising committees. Though she was unqualified, she began to teach, and taught little more than endless catechism lessons. The school operated at a loss until 1935.

In political terms she also seemed ill-equipped to cope with the prominent position her sons’ fame had bequeathed her. However, she was eager to help in the independence struggle and protected many men on the run. Elected to the dáil in 1921, she spoke against the treaty, invoking her sons at every turn. She was defeated in her constituency, Dublin County, in 1922. During the civil war her home was raided by Free State soldiers, incidents echoing the often violent intrusions of the Black and Tans during the war of independence. In many respects she was considered a figurehead, a representative of her two dead sons. She spoke at the reception that followed the first dáil, was elected to the Co. Dublin board of guardians, was on the executive of Fianna Fáil, started the printing presses for the first copy of the Irish Press (5 September 1931) and spoke regularly in Ireland and America, giving her ‘Pat and Willie’ speech. These positions were a tribute to her bereavement, an alignment with the tradition of 1916 she had now come to embody.

Some, however, objected to her status: by 1922 the Cumann na mBan convention debated her removal from its executive; Kathleen Clarke felt she distorted the truth of 1916, diminishing the importance of her husband, Tom Clarke. Eager to perpetuate the exaggerated vision of her sons, she denounced those who dared to question them, including John Devoy, who had lauded Tom Clarke as the main revolutionary figure of the rising. She was criticised for turning her sons into party political figures, finding, first in Liam Mellows, whom she sheltered in 1916, and second in Éamon de Valera, the successor to Patrick. Remembered most as the mother figure of Patrick Pearse's plays and poems, she died 22 April 1932 at St Enda's. She was accorded a state funeral, and her body lay in state at City Hall before burial at Glasnevin cemetery. Her funeral was one of the largest in the history of the state and Éamon de Valera's graveside oration was broadcast on 2RN. A death mask was taken by Jerome Connor.

Her daughters, Margaret Pearse (1878–1968) and Mary Brigid Pearse (1888–1947), both lived in the shadow of their brother Patrick. Margaret was born on 4 August 1878 at 27 Great Brunswick Street, and Mary Brigid was born on 29 September 1888, by which time the family had moved to Newbridge Avenue, Sandymount. They were both educated at the Holy Faith convent, Glasnevin, Dublin, and neither married nor consistently sought paid employment, but further resemblances are scarce and they were often on poor terms.

Robust, intelligent, and dogmatic, Margaret was close to Patrick. She shared his interest in education and together they travelled to Belgium in June 1905. In 1907 she founded an infant school at the family home in Leeson Park, and this may have encouraged Patrick to establish St Enda's. Margaret was an important support at St Enda's, running a preparatory school, teaching French, acting as matron and keeping in touch with the boys over the summer. Mary Brigid ‘was a pitifully delicate child, always ailing and nearly always confined to bed’ (Mary Brigid Pearse, 80); she may have been the model for the sickly boy in Patrick's story ‘Eoineen na néin’. She was close to Willie, sharing his artistic inclinations. They established the Leinster Stage Society, for which she wrote some original pieces and adapted some Dickens for the stage. They had moderate success until a calamitous run at the Cork opera house in 1912.

The sisters reacted very differently to their brothers’ revolutionary activity. Margaret was supportive and gloried in their sacrifice, while Mary Brigid, who had gone to the GPO in an attempt to persuade them to come home, avoided the city centre in later life. Margaret helped her mother to run St Enda's, taking on more and more of the teaching responsibilities. She inherited the school and grounds on her mother's death and kept the enterprise limping along until 1935. Mary Brigid, while in many ways estranged from the family, remained financially dependent. She continued to write, having already one dreadful novel, The Murphys of Ballystack, published in 1917. She also wrote some children's stories and contributed articles to magazines such as Our Boys: it published several articles by her on the childhood of her brother in 1926 and 1927. An extended version of these was published as The home life of Pádraig Pearse (1934). If this signalled that Mary Brigid was thoroughly reconciled to her brother's place in history, then it was the cause of further division with Margaret, as they squabbled over royalties accruing from a brief autobiographical fragment of Patrick's that formed part of the book. Mary Brigid made several broadcasts about Patrick's life in 1939. She died suddenly 13 November 1947 at 6 Beaufort Villas, Rathfarnham, Co. Dublin.

Margaret became the public face of the Pearse family legacy. She was elected a TD, winning the eighth and final seat for Fianna Fáil in the constituency of Co. Dublin in 1933. She polled better, but lost out, when it became a five-seat constituency in 1937. She became a senator in 1938 and remained so (often on the taoiseach's nomination) until her death. She had a close relationship with Éamon de Valera, serving on Fianna Fáil's national executive and as an honorary treasurer for many years. She continued to live in the Hermitage, allowing it to house a Red Cross hospital during the second world war. In 1966 she received an honorary D.Litt. from the NUI, with other relatives of those executed in 1916. In the same year she announced that on her death she would leave the then decaying Hermitage to a religious foundation rather than the state, but was quickly persuaded to change her mind. She died 7 November 1968 at Linden convalescent home (where she spent her final years).

This biography is reproduced here by kind permission of the Dictionary of Irish Biography.

Kathleen Clarke / Courtesy of the National Library of Ireland

Kathleen Clarke

Kathleen Clarke was a Member of the second Dáil and the short lived fifth Dáil, and was later nominated to the Seanad. She started her own business at the age of 18 but later dedicated her life to working for Irish independence. After the Easter Rising, with the leaders executed or imprisoned, Kathleen Clarke was instrumental in continuing the campaign for independence and was imprisoned in Holloway Prison. In 1939, she became the first woman Lord Mayor of Dublin.

Clarke, Kathleen (Caitlín Bean Uí Chléirigh) (1878–1972), republican activist, was born 11 April 1878 in Limerick, the third daughter of Edward Daly (d. 1890), a timber measurer, and Catherine Daly (née O'Mara), a dressmaker. The Daly family were prominent republicans; her father and, more notably, her uncle John Daly were Fenian activists. Educated locally, she was apprenticed to a seamstress, and, at the age of eighteen, started her own dressmaking business; this venture was highly successful, and by 1901 she was manager of a thriving dressmaking firm in Limerick. She met Tom Clarke , a close friend of her uncle, in 1899, after his release from Portland prison, and in July 1901 she left Ireland to marry him in New York. For a time they ran a shop in the city and later farmed a market garden at Manorville, Long Island. However, the desire to renew his Fenian activities made Tom Clarke eager to return to Ireland, and in 1907, after some persuasion, his wife agreed to leave the USA. They settled in Dublin, opening a tobacconist's shop at 55 Amiens St., and later a second at 75a Parnell St., which they ran together.

Kathleen Clarke immersed herself in the republican cause, assisting with the production of Irish Freedom, the IRB newspaper founded in 1910. She was among those who attended the first meeting of Cumann na mBan in April 1914, and, as president of its central branch, ran first-aid classes and rifle and signalling practice. She also organised the publishing of successful pamphlets on Irish rebels. Before the Easter rising the supreme council of the IRB chose her as confidant for their plans; in the event of their arrest she was responsible for maintaining contact with John Devoy in America. After the collapse of the rising she was arrested and imprisoned briefly in Dublin castle (1–3 May). Her husband was executed 3 May and her brother Edward Daly the day after; she visited both men at Kilmainham jail. Her husband had entrusted her with £3,100 of the IRB's funds to relieve distressed republicans, and within days of his death she had established the Volunteer Dependants' Fund and was distributing assistance. Impressed by Michael Collins, she appointed him secretary to the fund, giving him his first position of administrative responsibility within the republican movement. She also continued to liaise with Clan na Gael associates in the USA. However, in late 1916 ill health resulting from a miscarriage and from the effects of mental strain led her temporarily to abandon her work.

As a vice-president of Cumann na mBan and a member of Sinn Féin's executive, Clarke addressed the question of women's rights during Sinn Féin's 1917 convention. With Jenny Wyse Power she presented a successful motion which ensured that equal rights for women became party policy. Her involvement with these groups led to her arrest during the ‘German plot’ scare of May 1918, when republicans were arrested on suspicion of conspiracy with Germany. She was held in Holloway prison with Maud Gonne MacBride and Constance Markievicz. As she was the mother of three children her detention caused considerable outcry, and during her imprisonment she was granted the freedom of Limerick City. She was also nominated by the Dublin City constituency council for election as a Sinn Féin candidate for the Clontarf division, though her nomination was subsequently blocked by Harry Boland in favour of Richard Mulcahy. Poor health led to her release from prison on 18 February 1919.

In that year she was first returned to Dublin corporation as a councillor, representing both the Wood Quay and Mountjoy wards. In this role she campaigned for the official recognition of the Sinn Féin government, and played an active role on various committees, including the Harcourt Street Children's Hospital board, and the school meals committee, of which she was chairman. She was a member of the Sinn Féin Dublin north city judiciary, and in 1920 was appointed president of the court of conscience and the children's court. In her capacity as a founder member of the Irish White Cross (1920), she was influential in the establishment of the Orphans' Care Committee. Throughout the war of independence her home was regularly raided by the Black and Tans.

Usually known as Mrs Tom Clarke, she fought hard to promote and defend her husband's memory, believing that he had not been given due recognition for his part in organising the 1916 rising; she constantly maintained that he, rather than Patrick Pearse, had been president of the provisional government. Elected to the dáil for Dublin Mid in 1921, she voted against the treaty. Unyielding in her republican principles, she declared she would accept nothing less than the republic for which her husband had died, and was dismissive of plans launched by Éamon de Valera for ‘external association’ with the British commonwealth. She later chaired negotiations aimed at avoiding civil war, but maintained her fierce opposition to the treaty. Having lost her seat in 1922, she continued to work for the Dependants' Fund, and in 1924 travelled to the USA to raise funds. A member of Fianna Fáil from its inception, she was re-elected as a TD for Dublin North in June 1927, and, after initial reservations, entered the dáil, only to lose her seat the following September. She accepted a nomination for the senate in 1928, and clashed with de Valera, whom she regarded as duplicitous and manipulative, when he asked her to stand down on the grounds that too many women had Fianna Fáil nominations; she refused, was elected, and remained in the senate until its abolition in 1936.

During these years her alienation from the party leadership increased. As a senator she opposed section 16 of the 1935 Conditions of Employment Bill, on the grounds that many of its provisions conflicted with women's rights as granted in the 1916 proclamation of the Irish republic. She again found herself expressing a minority view when, on the death of George V in 1936, she opposed the senate's motion of condolence to the British royal family. Her adherence to women's rights led her openly to criticise the 1937 constitution, thus making her a target of attack for many of the party rank and file. In 1939 she became the first woman lord mayor of Dublin. She served in this capacity until 1941, during which time she removed all traces of past British authority from the office, including having portraits of British monarchs carted away from the Mansion House. While lord mayor, she played a leading role in founding the Irish Red Cross, chairing its first meeting in the Mansion House in 1939.

Believing that de Valera's repression of the IRA during the second world war was excessively severe, she broke with Fianna Fáil in 1941, and, as an independent with no organisational support, lost her seat on Dublin corporation. In 1948 she stood unsuccessfully as a Clann na Poblachta candidate for Dublin North East, after which she concentrated on her work for various humanitarian causes. She also kept up her associations with both the Wolfe Tone Memorial Fund and the National Graves Association. She received an honorary LLD from the NUI in 1966, along with other relatives of the signatories of the 1916 proclamation. In 1965 she settled with her son Emmet in Liverpool, where she was a prominent and popular member of the Irish community. She died 29 September 1972, and, after a state funeral in the pro-cathedral in Dublin, was buried at Deansgrange cemetery.

This biography is reproduced here by kind permission of the Dictionary of Irish Biography.

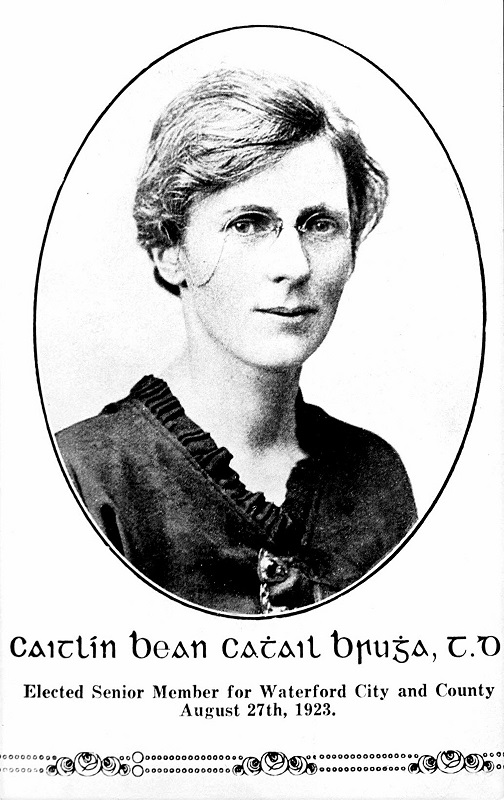

Caitlín Brugha

Caitlín Brugha

Caitlín Brugha was elected to the fourth Dáil in 1923 and was re-elected in 1927. Her seat had previously been held by her husband, Cathal Brugha, who had been killed fighting for the Republican side in the Civil War the previous year. Caitlín opposed the Free State government and abstained from taking her seat. Her son, Ruairí, also went into politics and served in both Dáil and Seanad Éireann.

Caitlín Brugha was elected at the first election after her husband's death. She took his Waterford seat, topping the poll. Born in Birr, County Offaly, where her family had been in business for over a century, in 1910 she moved with her family to Dublin where she rejoined the Gaelic League and there met Cathal Brugha whom she married on 12 February 1912. Cathal Brugha was a founder director of Lalor Ltd., candle manufacturers, IRA chief of staff 1917-18 and acting president of the meeting of the 1st Dáil in 1919.

Throughout the 1916 Rising, Caitlín Brugha actively supported the Volunteers, while her husband was second in command at the South Dublin Union.

“Does any man contemplate with equanimity a renewal of the conditions in this country in which his wife [Caitlín Brugha] will be dragged in the dead of the night out of her house, hustled along through the garden, and put into a motor lorry, and kept there in order that she will not be present while her husband is being murdered if the English cut-throats can get him?”

Cathal Brugha, Treaty Debate, Dáil Éireann Official Report, 7 January 1922, col.328

Caitlín Brugha was bringing up a young family when her husband was mortally wounded, emerging from the back door of the Hammam Hotel, Upper O’Connell Street, Dublin, while fighting on the Republican side in July 1922. He died two days later. Caitlín Brugha made a public request for the women of the Republican movement alone to act as chief mourners and guard of honour at her husband’s funeral. Her decision was a protest, she declared, against the civil war which had been waged by the [Free State] government against Republicans.

In January 1924, Caitlín Brugha established Kingston’s Ltd., a drapery business, in Nassau Street. In 1928 the business was transferred to Hammam Buildings, Upper O’Connell Street, where Cathal Brugha had been shot in 1922. Later branches were established in Grafton Street and George’s Street. She is buried in Glasnevin Cemetery.

This biography is an extract from "Women in Parliament, Ireland 1918-2000" by Maedhbh McNamara and Paschal Mooney.

Margaret Collins-O'Driscoll / RTÉ Photographic Archive

Margaret Collins-O'Driscoll

After her brother, Michael Collins, was shot dead in 1922, Margaret Collins-O'Driscoll was elected to the fourth Dáil. She was re-elected three times, and was the only woman elected to the sixth Dáil.

O'Driscoll, Margaret Collins- (c.1878–1945), teacher and politician, was born in Woodfield, Clonakilty, Co. Cork, eldest of three daughters and five sons of Michael Collins, farmer, and Mary Anne Collins (née O'Brien). Her youngest brother was the revolutionary leader Michael Collins. A primary-school teacher, for many years she was principal of Lisavaird girls' national school in Clonakilty, and also taught in Dublin before retiring from teaching on health grounds in 1928. First elected to Dáil Éireann in the 1923 general election as Cumann na nGaedheal TD for Dublin North, she was reelected in 1927 (June and September elections) and 1932, losing her seat in 1933, after which she retired from politics. In 1924 she was one of seventeen Cumann na nGaedheal TDs who protested at the appointment of Peter Hughes as minister for defence, and in 1926 she was elected a vice-president of the party. The only female member of the dáil between September 1927 and 1933, she had an unexceptional parliamentary career, characterised by adherence to the Cumann na nGaedheal party line and a conservative attitude to social issues. In a dáil debate in 1925 she declared: ‘In the days of my youth it was regarded as a qualification for matrimony that a woman should be able to make her husband's shirts’; when voting for the 1928 censorship of publications bill, which banned indecent literature and publications that referred to birth control, she stated that ‘... no vote I have ever given here, or will ever give, will be given with more satisfaction than the vote I will register in favour of this bill’; and she voted with the government in favour of the 1924 and 1927 juries bills, which restricted jury service for women.

She married (8 September 1901) Patrick O'Driscoll, journalist, owner of the West Cork People, and later a member of the oireachtas reporting staff, son of Patrick O'Driscoll, a farmer of Clonakilty. They had five sons and nine daughters and lived at 147 North Circular Road, Dublin. She died 17 June 1945 in Dublin, leaving an estate valued at £2,685.

This biography is reproduced here by kind permission of the Dictionary of Irish Biography.

Jennie Wyse Power / Courtesy of Kilmainham Gaol Museum KMGLM 2015.0673

Jennie Wyse Power

Jennie Wyse Power was a Member of the first Seanad, from 1922 until it was abolished in 1936. She had been active in politics since 1881, first as a member of the Ladies' Land League and later as a suffragist and nationalist. Her restaurant on Henry Street became a meeting place for Republican leaders and the 1916 Proclamation was signed there. As a Senator, she spoke against a series of laws discriminated against women.

Power, Jennie Wyse (1858–1941), nationalist and suffragist, was born Jane O'Toole in May 1858 in Baltinglass, Co. Wicklow, youngest among four sons and three daughters of Edward O'Toole (d. 1876), shopkeeper and small farmer, and Mary O'Toole (neé Norton; d. 1877). The O'Tooles were strongly nationalist and she joined the Ladies' Land League in 1881, becoming a league organiser in Wicklow and Carlow and acting as librarian to land league prisoners. As a member of the executive of the Ladies' Land League she became friendly with Anna Parnell and a strong supporter of Charles Stewart Parnell . She remained loyal to Parnell despite his disbanding of the Ladies' League (1882). On 5 July 1883 she married fellow Parnellite and journalist John Wyse Power , and moved first to Naas, Co. Kildare, and then to Dublin (1885). The Wyse Powers had four children: Catherine (b. 1885), who died in infancy; Maura, called ‘Máire’ (b. 1887); Anne, called ‘Nancy’ (b. 1889); and Charles (b. 1892), named in honour of Parnell. She supported Parnell during the split, editing Parnell's speeches in Words of the dead chief (1892) and serving as treasurer to the committee that tended his grave. Jennie opened a shop and restaurant at 21 Henry St. Dublin, called ‘The Irish Farm and Produce Company’ (1899). This became a popular meeting place for many of the cultural and political organisations with which she was involved. She joined Conradh na Gaeilge, becoming a member of its executive in November 1900. The family holidayed regularly in the Gaeltacht at Ring, Co. Waterford, where she was a member of the board of management of the Irish college.

She was a member of the Dublin Women's Suffrage Association and represented the National Women's Committee at the Franco–Irish celebrations in Paris (1900). Also in 1900 she was a co-founder and vice-president of Inghinidhe na hÉireann and a member of the committee that organised the Patriotic Children's Treat as a counter-attraction to the visit of Queen Victoria. She was elected a member of the board of guardians of North Dublin Poor Law Union (1903–12), representing the National Council of Arthur Griffith and, from 1908, Sinn Féin. She was a constant on the executive of Sinn Féin, serving as a joint or sole treasurer at various times and becoming vice-president (1911). In 1912 she was disappointed when Griffith voiced support for the Irish parliamentary party's decision to vote against the conciliation bill, which would have extended a limited franchise to women. In the same year she joined the committee founded to support Hanna Sheehy Skeffington who had been sacked and jailed because of suffragette activities; she also took Skeffington daily meals while in Mountjoy. She was a founder member of Cumann na mBan (1914) and its first president (1915), and a member of Cumann na dTeachtaire (a women's group within Sinn Féin) and the Irish Women's Franchise League. Her business had expanded to four shops, but Henry St. was still the headquarters. It was here that the proclamation of the republic (1916) was signed. Jennie and Nancy carried food from the restaurant to the rebels in the GPO as late as Wednesday in Easter week.

After the rising she was involved in the Republican Prisoners' Dependents' Fund and again became treasurer of Sinn Féin after the ‘German plot’ arrests of May 1918. In 1920 she was elected to Dublin corporation. She took her seat after a row with the council clerk, who initially refused to accept her signature in Irish. She was chairman of the finance and public health committee of the corporation and a governor of Grangegorman mental hospital. She was the only leading member of Cumann na mBan to support the treaty and join Cumann na Saoirse. As joint treasurer of Sinn Féin with Éamonn Duggan , she froze the party's accounts, refusing republicans access to the money. She was appointed to the executive of Cumann na nGaedheal and nominated to the senate (1922). When Dublin corporation was dissolved for refusing to strike a rate, she was one of the commissioners appointed to run the city (1924–9).

By 1925, however, she had become disillusioned with Cumann na nGaedheal and resigned from the party in dissatisfaction with social and economic policy and the result of the boundary commission. She continued to serve as an independent senator, being particularly vociferous on matters relating to women's status. She spoke against the Civil Service Regulation (Amendment) Bill (1925), the Juries Bill (1927), and the Conditions of Employment Bill (1935) because she felt they discriminated against women. At this time she was a member of the Irish Women's Citizens' and Local Government Association. She represented Fianna Fáil in the senate from 1934 until its dissolution in 1936. Having sold her business in 1929 she had a period of complete retirement from 1936 until her death at home, 15 Earlsfort Terrace, Dublin, on 5 January 1941. She left £5,308 to her son, Charles.

This biography is reproduced here by kind permission of the Dictionary of Irish Biography.

Margaret Cousins / By kind permission of Keith Munro, grandnephew of Margaret and James Cousins

Margaret Cousins

Margaret Cousins was one of the co-founders of the Irish Women's Franchise League. She travelled to England to learn militant tactics, marched in Black Friday and was imprisoned in Holloway. In 1913 she was jailed in Tullamore prison for breaking windows. After moving to India, she continued to campaign for women's rights and became the first female magistrate in India.

Cousins, Margaret (‘Gretta’) Elizabeth (1878–1954), suffragist, educator, and theosophist, was born 7 November 1878 in Boyle, Co. Roscommon, eldest of fifteen children of Joseph Gillespie, petty sessions clerk, and Margaret Annie Gillespie (née Shera). Brought up in a unionist and methodist household, from an early age she sympathised with nationalism. She was educated locally until 1894, when she was awarded a scholarship for the Victoria High School for Girls in Derry. She went on to study at the Royal Academy of Music in Dublin (1898), graduating B.Mus. from the RUI in 1902.

After her marriage (1903) to James Cousins, she was determined to maintain her independence, and worked part-time as a music teacher. Through her husband she became familiar with many of the leading literary figures in Dublin, among them James Joyce, who briefly stayed with the Cousinses in their Ballsbridge home (June 1904), and George Russell with whom they shared an enthusiasm for theosophy. She experimented with automatic writing and astrology, and acted as a medium at seances in her home. Like her husband she became a vegetarian, and on the foundation of the Irish Vegetarian Society (1904) was appointed its honorary secretary. In 1906, while visiting England to address a vegetarian conference, she also managed to attend the conference of the National Council of Women. This inspired her to join the Irish Women's Suffrage and Local Government Association on her return to Ireland. However, she soon became frustrated by their timid approach, and with Hanna Sheehy Skeffington founded the militant, non-party Irishwomen's Franchise League in 1908. Having initially served as its treasurer, in 1911 she was appointed as its honorary secretary. As one of its most influential and high-profile members she regularly spoke at its open-air meetings in Dublin and on suffrage tours of the country, irrespective of the occasional hostility which at times greeted her addresses. The suffrage paper, the Irish Citizen (co-founded by her husband) mentions her having addressed meetings in Kerry, Donegal, Sligo, Enniskillen, Portrush, and Mayo (8 February 1913). She also lobbied Irish MPs – most particularly the IPP leader and key suffrage opponent John Redmond – and the chief secretary, Augustine Birrell (1910).

Cousins maintained her links with English suffragists and in July 1909 worked for the Women's Social and Political Union in London. In November 1910 she was among the six Irish representatives at the ‘parliament of women’ in Caxton Hall, London. During her stay in London she was convicted of smashing the windows at 10 Downing St., and served a one-month sentence in Holloway prison. This failed to deter her militant fervour, and she subsequently took part in protests at the failure of the home rule bill to provide female suffrage, during Asquith's visit to Dublin in 1911, and spoke at a mass meeting at the Antient Concert Rooms, Dublin, to demand the inclusion of women in the bill (June 1912). She was jailed for one month (January 1913) with fellow IWFL activists Margaret Connery and Mrs Hoskins for breaking the windows at Dublin castle; during their imprisonment in Tullamore jail they successfully fought for political status in prison after a brief and well publicised hunger strike, which came to a head after Hoskins suffered a heart attack.