The debate on the Treaty would be attended by an unprecedented number of press from home and abroad. Dáil Éireann faced the challenge of organising a venue suitable for the event.

The Round Room of the Mansion House was being used for Aonach na Nollag, an annual Christmas fair of Irish goods, and its Oak Room was deemed too small for the occasion. Crowding or discomfort would not only appear bad, but there was also concern that it was likely to have an impact on the conduct of proceedings and make it very difficult to preserve the order and seriousness that the occasion demanded.

The Second Dáil held its initial public sittings in the Round Room of the Mansion House / Image courtesy of the National Library of Ireland

The dining hall of University College Dublin’s building in Earlsfort Terrace, now the National Concert Hall, was considered first before Eamon de Valera, President of Dáil Éireann, requested the use of the university’s Council Chamber for the historic meeting. UCD often declined requests to use its premises but it was not likely that it would refuse the Dáil Éireann, nor a request which came from the Chancellor of the NUI.

The president of UCD informed the governing body that he had granted permission for its use “for the important meeting of Dáil Éireann now being held, and that he had instructed the servants in the College Lunch Room to provide tea for the members and officers of the Dáil”. It was decided to pay the women attendants in the lunch room £2 each and the College porters £1 each for extra work in connection with these meetings, funds which were recouped from Dáil Éireann some months later.

Crowds outside the Treaty Debates on Earlsfort Terrace / Courtesy of the National Library of Ireland

Thinking back to the debates many years later, Robert Briscoe, the anti-Treatyite and future Deputy, remembered a room “immensely long and narrow, about one hundred feet in length and perhaps thirty feet wide”. The Council Chamber was a double-length, low-ceilinged room upstairs, and is now the Kevin Barry Rooms in the concert hall. Briscoe also recalled:

"The Speaker, Eoin MacNeill, presided at the south end of the room, and the Deputies sat on folding chairs interspersed with tables all higgledy-piggledy down the long room."

Because the ceiling of the Chamber was so low its acoustics were nearly non-existent. Not only was it almost impossible for members in the back of the hall to hear what the orators were saying, it was difficult even to see who was speaking. Frank Gallagher, who had until recently worked with the Dáil Éireann propaganda department and who opposed the Treaty, recalled:

“The deputies were crowded at one end and the Press of the world at the other. Somewhere down in the basement there were dining-rooms, and many an evening at the tea adjournment I sat there as these men of national renown were discussing among themselves what was to happen now.”

As ever, perhaps as much of the politics took place over tea as it did on the floor of the House.

If some of the proceedings were somewhat chaotic, the real wonder is that they ran as smoothly as they did.

Even if, according to Robert Briscoe, “a worse place to hold a parliamentary meeting is hard to imagine”, there were certain advantages to the venue. For one, the use of Earlsfort Terrace restricted access to the public, which, as David McCullagh noted was no bad thing in some eyes:

"When a move back to the Mansion House was suggested after the Aonach concluded, both de Valera and Griffith opposed it, on the grounds that there would be a tendency for partisan crowds to cheer speeches".

Professor Eoin MacNeill, the Speaker, presided, assisted by a Deputy Speaker, Brian O’Higgins. (Seán T. O’Kelly had been elected Deputy Speaker in August but had stepped down shortly afterwards). They were assisted by clerks and there was a desk where reporters, led by the Independent journalist and volunteer in the Dublin Brigade, Michael Knightly, took shorthand notes of proceedings.

It was unlike any previous meeting of Dáil Éireann, an assembly which had almost no permanent staff, which had up to then passed no legislation and had never even had to take a vote. If some of the proceedings were somewhat chaotic, the real wonder is that they ran as smoothly as they did.

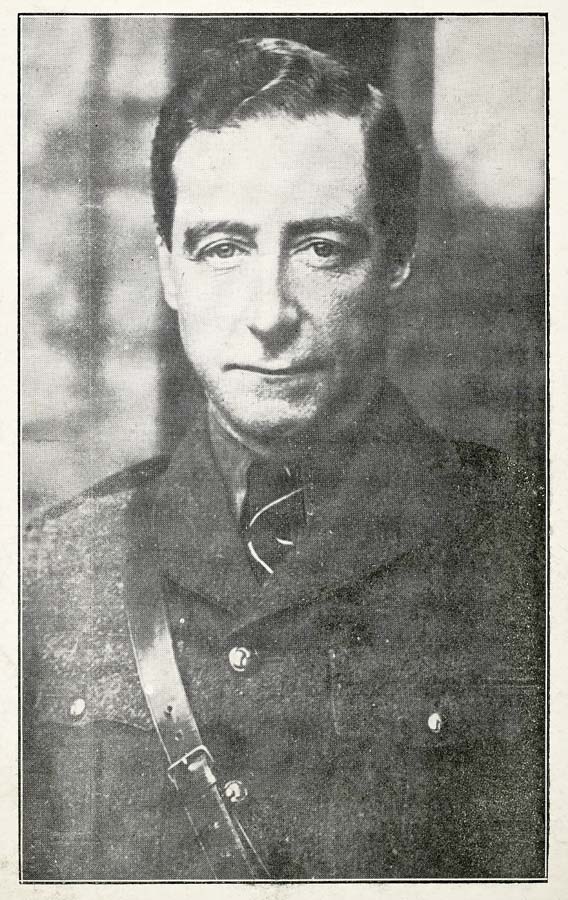

Cathal Brugha's observations on the state of the army were considered so confidential that they were not put on paper / Image courtesy of the National Library of Ireland

The debate opened with disagreement on what matters should be up for discussion. Eventually it was decided to go into private session, de Valera remarking “We probably could dispose of the points of difference in an hour”. In fact, the meeting continued in private all day and went on for a further three days, with a further private session on Friday 6 January.

A verbatim account of these proceedings was made by Michael Knightly and his hastily assembled team of reporters, using shorthand notes. The public sessions were published not long after the debates (although the bound volumes were not produced until October 1923) but the private sessions of both the Treaty Debates in December and the debates in August and September before the negotiations, were locked in a safe and remained private for another fifty years.

Dáil Éireann had not yet in place a dedicated Debates Office with parliamentary reporters. That meant the debates were written by a somewhat inexperienced crew of reporters under quite stressful conditions.

During the 1960s, there began a process to prepare the material for release but its quality was such that an historian had to be asked to prepare it for publication. The Dáil Committee on Procedure and Privileges invited Thomas P. O’Neill, then lecturer in history at University College Galway and co-author of a biography of Eamon de Valera, to do the job. The result was published in 1972.

Dáil Éireann had not yet in place a dedicated Debates Office with parliamentary reporters. That meant the debates were written by a somewhat inexperienced crew of reporters under quite stressful conditions. When T.P. O’Neill came to review the draft typescripts of the private sessions, for which no shorthand notes remained, he found some problems with parts of the text. As he wrote in his introduction:

"Part of a speech in Irish by Pádraig Ó Maille on 16 December 1921 was not recorded while a speech in that language by Fionan Ó Loinsigh was summarised in English. There were more obvious reasons why a statement by Cathal Brugha on defence was not recorded. His observations, and those of members who were army officers, on the state of the army were considered so confidential that they were not put on paper. Apart from this it appears clear from the text that a speech ascribed to Countess Markievicz on 17 December was not in fact delivered by her, while another on the same day ascribed to Liam de Róiste would appear to have been delivered by Sean Etchingham. These points are mentioned as warnings to those who use this report that it must be used with care."

Some of the conventions that had been used in the earlier reporting of debates, such as the identification of Ministers by office, rather than by name, had been abandoned. There were also some issues around the spelling of people’s names, so that, for instance, Seán Mac Eoin appears as Sean MacKeown and Joseph McGrath’s name appears with the prefix "Mac". O’Neill corrected the errors in the original typescript, marking the changes with recte, and these corrections are in the online version.

The UCD Council Chamber at Earlsfort Terrace where the Treaty Debates took place / Courtesy of the National Library of Ireland

Some mistakes were inevitable, but there were remarkably few not least considering the inexperienced reporters and the circumstances in which they were working, among them a room in which it was so difficult to hear. Of course, the mistakes would have been picked up had the debates been published at or closer to the time. Indeed, as the pro-Treaty Deputy Professor Michael Hayes later noted of the Official Reports of the public sessions (1919-22) they were “accurate and accepted”. Notwithstanding O’Neill’s caveats, the private sessions proved an important source for historians, recording as they did the debates around Document No. 2 that had been adverted to throughout the public sessions.

The private sessions both of the Treaty Debates in December, and those in August and September before the negotiations, were locked in a safe and remained private for another fifty years.

As invaluable as the text of the debates are, they do not give the full story. As the Irish Independent reporter Padraig de Burca noted after one exchange, one would need to have been present to appreciate the cross-fire, which was in good humour among people who were, at that point, still friends. Frank Gallagher noted that the "scene was marked more by sadness than by the anger which so often glowed on the surface". After the debates on the Treaty had concluded, the Dáil returned to the Mansion House. While the new President, Arthur Griffith, and his predecessor, Eamon de Valera, expressed their thanks to UCD for allowing Dáil Éireann the use of the premises, there must have been considerable relief among most of those present that they might never have to see the inside of the Council Chamber again.

History of the Debates Office

The Debates Office was established in 1922 to produce the official report, and it continues to do fundamentally the same job today. You can find out about parliamentary reporting through the decades on the Dáil100 website.