This exhibition showcases examples from the Documents Laid collection for each decade since the 1920s, and provides an insight into some of the significant events in Irish society over the past ninety years.

Kilmainham Prison (Closing) Order 1929

1920s

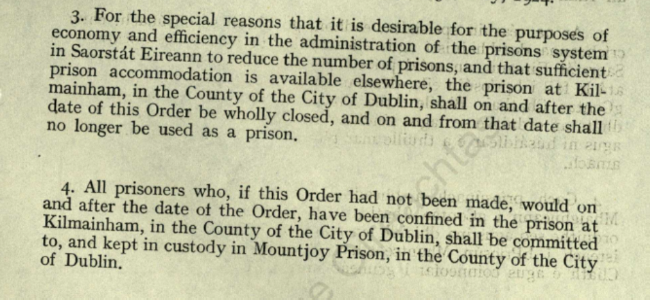

Kilmainham Prison (Closing) Order 1929

Kilmainham Gaol, in operation since the late 18th century, was decommissioned as a prison following the Irish Civil War, and was formally closed in 1929. The gaol first opened in 1796 as the new county gaol for Dublin, with debtors, thieves, drunks, beggers and prostitutes confined within its walls and prisoners found guilty of murder and violent robbery publically executed by hanging.

Also held within Kilmainham were those sentenced to be transferred to penal colonies in Australia during the first half of the 19th century, as well as prisoners held on charges of begging and stealing food during the famine. Political prisoners were also confined in Kilmainham, with many of the Irish leaders of the 1798, 1803, 1848, 1867 and 1916 rebellions held in the gaol. Robert Emmet, the leader of the 1803 rebellion against the British, was but one notable figure held in Kilmainhham Gaol, having been confined there prior to his execution on Thomas Street on the 20th of September 1803.

Kilmainham itself saw a number of executions. From the 3rd to the 12th of May 1916, the fourteen leaders of the Easter Rising were executed by firing squad in Stonebreaker’s Yard, and, following the Irish Civil War a few years later, executions of anti-treaty Republican prisoners took place by order of the Government of the Irish Free State. Other former prisoners of Kilmainham Gaol include James Napper Tandy, Charles Steward Parnell, Countess Markievicz, and Eamon De Valera, the last prisoner to be released from Kilmainham Goal who later went on to serve as Taoiseach and as President of Ireland. The prison was closed down shortly after de Valera’s release on the 16th of July, 1924.

The possibility of reopening Kilmainham as a prison was considered by the Irish Prison Board during the 1920s. However these plans were abandoned, and, on the 1st of August 1929, a statutory order was made by Minister for Justice James FitzGerald-Kenney which formally closed the premises (an excerpt of which can be seen above). Following its closure, Kilmainham was let fall into ruin. In 1936, there were proposals to demolish the gaol but these were abandoned due to the high costs involved. The late 1930s saw increased interest in the preservation of the site with a proposal from the National Graves Association to develop the site as a memorial to the 1916 Rising, but this was deferred with the onset of the World War II. After the war, an architectural survey commissioned by the Office of Public Works recommended that the prison, with the exception of the prison yard and historically significant cell blocks, be demolished.

Fortunately, this was not acted on. Instead, in 1958, a voluntary group known as the Kilmainham Jail Restoration Society was formed with plans to repair the prison and re-develop it as a museum. Over the following decade, these plans were implemented, and in 1971, the final restorations were completed and the site was opened to the public as a museum on the history of Irish nationalism. The Kilmainham Jail Restoration Society continued to manage the gaol up until the mid-1980s, at which point the Office for Public Works took over its running. To this day, Kilmainham Gaol continues to operate as a national monument and the museum holds a historically significant collection of Irish nationalist and republican material. It is currently one of the most popular tourist attractions in Dublin.

From the Documents Laid Collection, DL066755

Emergency Imposition of Duties (No. 1) Order 1932

1930s

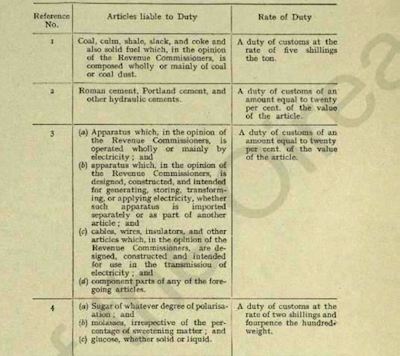

Emergency Imposition of Duties (No. 1) Order 1932

The 1930s saw the Fianna Fáil party, under the leadership of Eamon De Valera, elected into government. From the outset, they were eager to dismantle parts of the 1921 treaty considered restrictive to Irish independence. To achieve this, De Valera amended the constitution to remove the Article requiring the taking of the Oath of Allegiance by newly elected members before they could claim their seats in the Dáil or Senate, while also downgrading the post of Governor General by appointing a close friend who never took up office or exercised any official function.

The post was later abolished in 1937.

Of particular significance was the decision to withhold repayments of the Land Annuities. The Land Annuities were consequent of the loans advanced by the British government under the Land Acts of the late 19th and early 20th century in order to enable Irish tenant farmers to purchase land. Their repayment, along with payment of contributions towards the Free State’s share of the public debt, were conditions under the 1921 treaty to which the previous Cosgrave government had agreed. The 1925 London Agreement relieved the Free State government of all outstanding debts; however, the land annuities were not included in this, and the Free State continued to pay back the loans for a further seven years. Upon becoming Taoiseach, de Valera declared that the land annuities ought to have been annulled along with the other outstanding debts, and decided to withhold payment of future annuities. This decision led to what became known as the Anglo-Irish Trade War (also referred to as the Economic War).

Following the failure of the Free State government to repay the loans, Britain responded by imposing significant import duties on Irish goods coming into the country in order to recover their losses, to which the Free State retaliated in kind. In 1932, the Free State government passed the Emergency Imposition of Duties Act in 1932, which allowed them, amongst other things, to “impose, whether with or without qualifications, limitations, drawbacks, allowances, exemptions, or preferential rates, a customs duty of such amount as they think proper on any particular description or descriptions of goods imported into Saorstát Eireann on or after a specified day and, where such goods are chargeable with any other customs duty, so impose such first-mentioned duty either in addition to or in substitution for such other duty”.

Discussions between the Free State and Britain were initiated to bring about a resolution to the trade war, but quickly fell apart following disagreements over the establishment of an adjudication board, with the British government insisting it be made of British Commonwealth representatives, a term to which De Valera would not agree. Over the following five years, the Free State government passed a number of statutory orders, including the Emergency Imposition of Duties (No. 1) Order (pictured above), which passed on the 25th of July, 1932 and allowed for the imposition of duties on pigs meat, pork products, coal products, sugar, cement, electrical equipment, and cheese-making machinery, and facilitated changes to duties on potatoes imported from Great Britain and Northern Ireland.

Overall, Britain did not suffer greatly from the duties imposed on imported goods from Ireland. The Free State, on the other hand, depended heavily on exporting their produce to Britain, with the British market consuming up to 90% of Irish exported goods. With such reliance on UK markets, which were now unwilling to pay extra for Irish produce, the Free State suffered severely as a result of the war.

The Economic War, which lasted for five years in total, was brought to an end following pressure by British exporters and Irish farmers on their respective governments, and the Anglo-Irish Trade Agreement was signed on the 25th of April, 1938. The terms of the treaty stated that the tariffs imposed by both the Irish and British governments would be abolished and that the dispute over the repayment of the land annuities would be settled by a once-off payment of £10,000,000 by the Irish government. The treaty also allowed the return to Ireland of three ports – Berehavan in Co. Cork, Spike Island near Cobh and Lough Swilly in Donegal – which were kept by the British government under the terms of the 1921 Anglo-Irish treaty. Despite the sufferings imposed on the Irish people by the Economic War, the treaty was seen as a great success for Fianna Fáil, who remained in power up until early 1948.

25 July 1932

Taken from the Documents Laid Collection, DL057132

Air Raid Precautions Act 1939 (Grants under Section 58) Regulations

1940s

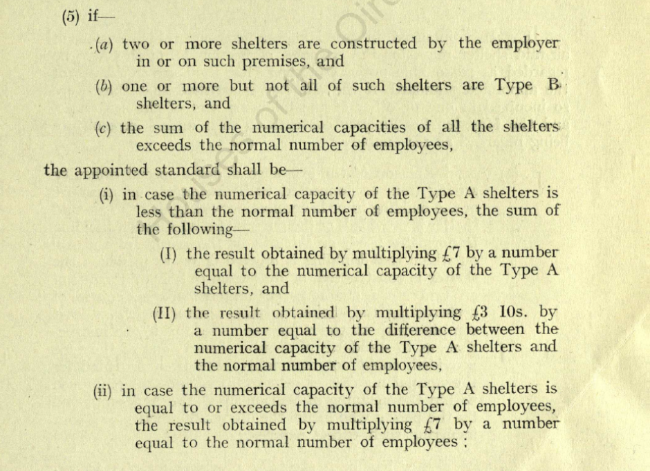

Air Raid Precautions Act 1939 (Grants under Section 58) Regulations

Throughout World War II, Ireland’s official policy was that of neutrality. However, as the United Kingdom was at war with Germany, Ireland needed to be prepared for the possibility of air-raids, and, indeed, the Republic was bombed by the German Luftwaffe a number of times between 1940 and 1941.

Attacks included an air-raid attack on the 26th of August 1940 in County Wexford, which killed three people, for which the German government paid £9000 in compensation in 1943, as well as bombings in Meath, Carlow, Kildare, Wicklow, Wexford and Dublin from the 1st to the 3rd of January 1941. Three people were killed in Carlow, and a number were injured during this spate of attacks. The worst attack occurred on the 31st of May 1941 when four German bombs fell on North Dublin, with the loss of 28 lives. After the war, West Germany accepted responsibility for this raid, and paid over £300,000 in compensation. It is now understood that a combination of navigational errors and mistaken targets were to blame for these attacks.

The Air-Raid Precautions Act passed in Ireland in 1939 and was modelled exactly on the Act that passed two years earlier in the United Kingdom. Under the Act, designated local bodies were required to prepare and submit to the Minister for Defence air-raid precaution schemes which would detail how civilians and property would be protected in the event of an air-raid. The Act gave powers to local authorities to aid them in carrying out air-raid preparations, including allowing them to acquire property for development into public shelters (once required notice and compensation was given to the owner), and outlining their responsibilities in aiding in the evacuation of civilians. It also required for lights to be extinguished or obscured during periods of darkness.

Under the Act, employers were also required to develop air-raid shelters for protection of employees, and the Act allowed for grant payments to be made for expenses incurred from the building and ongoing running of shelters. In preparation for impending air-raids, both trench and over-ground shelters were constructed, while basements of private businesses were also developed for use as shelters. Priority was given to cities and urban areas, particularly in Dublin and areas on the east coast. There were very few, if any, air-raid shelters in rural parts of Ireland.

Pictured above is an extract from a set of regulations, dated the 23rd of February 1940, and signed by Sean Moylan, Parliamentary Secretary to the Minister for Defence and Sean T. O’Ceallaigh, Minister for Finance, published under section 58 of the Air-Raid Precautions Act, 1939, which allowed for the payments of grants to employers in order to cover expenses incurred through the provision of air-raid shelter for employers. These regulations laid out information regarding the “appointed standards” relating to expenses acquired by the employer in securing the provision of air-raid shelters for their employees. The regulations also make provision for certain exceptions to the appointed standards, including excess expenditure arising from infrastructural complications in the building to be used as an air-raid shelter or problems arising from the everyday use of the building, the site it is built on, or the nature of the soil on which it sits, or in other cases where the standards laid out previously were not sufficient to provide shelter for the number of persons employed without sustaining extra expense. Shelters that were developed to specifically provide accommodation for casualties or for people engaged in Air-Raid Precautions Services could also be exempt from the appointed standards, should the Minister be satisfied that the excess expenditure was necessary.

To this day, there are still shelters scattered throughout the city, with many shelters under various buildings in Dublin, including in the basements of the Mary Aikenhead House on James Street and the Vero Moda shop on Grafton Street. The basement in Heuston Station was also reportedly available for use as a public shelter during the Emergency.

From the Documents Laid Collection, DL053255

Proposals for improved and extended health services, July 1952

1950s

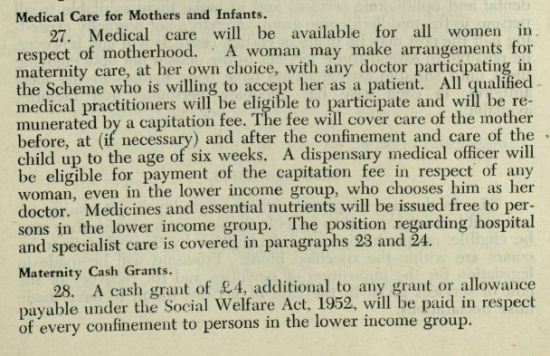

Proposals for improved and extended health services, July 1952

The 1940s and 1950s were a time of significant change for the healthcare system in the Republic of Ireland, with the establishment of the Department of Health to replace of the Department for Local Government and Public Health on healthcare-related issues and the development of sanatoria throughout Ireland in order to help eliminate tuberculosis. The Health Act of 1947 passed by Fianna Fáil introduced the topic of universal healthcare and made way for the Mother and Child Scheme controversy of the 1950s.

The Mother and Child Scheme was a divisive healthcare programme introduced by Minister for Health Noël Browne, which received major opposition from the Catholic Church and the medical profession, and, ultimately, led to Browne’s resignation. The programme planned to introduce free ante and post-natal care for mothers and to extend free healthcare to all children under the age of 16. Provision was made for such a scheme in section III of the 1947 Health Act passed by the 1944-1948 Fianna Fáil government; however, they were supplanted in the 1948 general election by a coalition government before they could begin to implement the scheme. Noël Browne of Clann na Poblachta became Minister for Health following the election, and in 1950 introduced his proposals for mother and children healthcare services. His proposals were quickly met with fierce resistance by both the Church and the medical profession. The Church cited the legislation as “anti-family”, expressing concern regarding the provision of family planning advice and what they claimed would be increased interference by the state in the parents’ rights to provide healthcare for their children. The decision to omit a means test from the scheme was one contested by both the clergy and medical professions, with private practice doctors fearing the impact that free healthcare would have on their income. The Catholic hierarchy wrote to Taoiseach John A. Costello to voice their concerns regarding the scheme; however, Browne was not made aware of this, and so, he continue to press forward with the scheme without realising the extent of Church enmity to his proposals.

Browne received little support from his colleagues in this matter, and the scheme was abandoned in April 1951 in favour of one that would be more in line with Catholic social teaching. In the days following this decision, Browne submitted his resignation following demands for such by Sean MacBride, his party leader. The resignation took effect from the 11th of April, 1951. In his resignation speech, Browne claimed acceptance of the Church’s position on the matter, but laid blame on the behaviour of his colleagues, stating “I as a Catholic accept unequivocally and unreservedly the views of the hierarchy on this matter, I have not been able to accept the manner in which this matter has been dealt with by my former colleagues in the government”.

Following his resignation, Browne passed on correspondence between the coalition government and the Catholic hierarchy to the editor of the Irish Times. This correspondence, which revealed the extent of influence that the Church had held on this matter, was subsequently published.

A month later, a general election was called, and Fianna Fáil returned to government in June 1951. Upon their re-election they set about reforming public healthcare, but were mindful of the need to compromise in order to avoid the resistance that had hindered Browne’s attempts. Pictured above is an excerpt from Fianna Fáil’s Proposals for Improved and Extended Health Services, published in July, 1952, which outlined their early plans for public health reform. In 1953, an altered version of original Mother and Child Scheme was passed into legislation under the 1953 Health Act. The 1954 Maternity and Infant Care Scheme differed greatly from Browne’s vision. Although it allowed for the provision of free maternity services, it was limited to maternity-related illnesses and was only available during pregnancy and for six weeks following birth. Also abandoned was the idea of free healthcare for all, with the scheme instead requiring individuals with incomes over a certain threshold to pay a contribution.

The rejection of Browne’s scheme shaped the provision of maternity services for the rest of the century, leading to a more medical model of childbirth and a decrease in the number of homebirths in Ireland. The latter half of the 20th century also saw the development of a two-tier health service resulting from the establishment of the VHI following from the passing of the Voluntary Health Insurance Board Act of 1957. A medical card scheme was introduced in the 1970s; however, in opposition of Browne’s vision, this was based on a means test. The Mother and Child Scheme controversy remains a noteworthy event in the history of Irish healthcare. It had a significant impact, not only in shaping the development of healthcare services, but also in igniting public debate on the relationship between Church and state and on the Church’s role in the shaping of public policy.

From the Documents Laid Collection, DL011492

RTÉ Annual Report for the year ending 31 March 1965

1960s

RTÉ Annual Report for the year ending 31 March 1965

Irish radio broadcasting began on the 1st of January 1926 when 2RN, the first radio station of the Irish Free State, began broadcasting from a studio in Dublin. 2RN succeeded by Radio Athlone in 1933, later becoming known as Radio Éireann in 1938. Radio Éireann operated as a section of the Department of Posts and Telegraphs up until 1960, when it was transferred to a new independent semi-state body set up under the Broadcasting Authority Act, 1960.

The 1960s also saw the arrival of the national television broadcasting service. The Television Commission was established in 1958 in order to investigate the development of television broadcasting in Ireland, and the 1960 Broadcasting Authority Act established Radio Éireann as the authority responsible for operating both radio and television as a public service. Under the Act, the authority was charged with establishing and maintaining a broadcasting service that was true to “the national aims of restoring the Irish language and preserving and developing the national culture and shall endeavour to promote the attainment of those aims” (Section 17). Between seven and nine members were appointed by the government and served for five years, with Eamonn Andrews appointed as the first chairman and Edward Roth as the first director-general. Television licences were introduced with the establishment of Telefís Éireann, though advertising revenue was also generated in order to support its maintenance.

Telefís Éireann first began broadcasting at 7pm on the 31st of December, 1961, and the launch saw addresses by President Eamonn DeValera, Taoiseach Sean Lemass and the Minister for Posts and Telegraphs, Michael Hilliard. In his opening address, President DeValera remarked on the impact television would have on Irish culture, stating that “never before was there in the hands of men an instrument so powerful to influence the thoughts and actions of the multitude”. The opening night programme also saw a blessing from the Archbishop of Dublin and Primate of Ireland John Charles McQuaid, readings of poems written by Padraig Pearse and W.B. Yeats, broadcasts of traditional music and dance, and a live transmission from the Gresham Hotel in Dublin. The first news bulletin was broadcast on the opening night of Telefís Éireann, read by Charles Mitchel, and the first televised weather forecast was broadcast the following day after the main evening news, presented by Met Éireann Meteorologist George Callaghan.

July 1962 saw the first broadcast of The Late Late show, hosted by Gay Byrne (who remained in this position until 1999), and, though originally attended only to run throughout the summer, it was so popular with audiences that it became part of the regular schedule and still runs to this day, being one of the two longest running chat shows in the world. Radio Éireann became formally known as Radio Telefis Éireann (RTÉ) in 1966, with changes in legislation renaming it to Raidió Teilifís Éireann in 2009. RTÉ’s second television channel, RTÉ Two, went on air in 1978.

Under the Broadcasting Authority Act, 1960, Radio Éireann was required to submit an annual report to the Minister regarding its activities during the preceding year. An excerpt from the 1965 annual report can be seen above. The report provides a review of progress up to date, an overview of television and radio programmes from the preceding year, engineering, staffing and building developments, information on advertisement sales, and a report of finances and accounts for the year. A PDF of the 1965 annual report can be accessed here.

From the Documents Laid Collection, DL006344

Membership of the European Communities, Implications for Ireland, April 1970

1970s

Membership of the European Communities, Implications for Ireland, April 1970

In the aftermath of the Second World War, there was an effort by Western European nations to foster co-operation and unity throughout Europe. In order to achieve this ideal, a number of communities were set up in the years following the war. The European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC) was founded in 1951, followed by the establishment of the European Economic Community (EEC) six years later.

The EEC was set up under the Treaty of Rome which was signed on the 25th of March by France, Italy, Belgium, West Germany, Luxemburg and the Netherlands. Eurotom, which sought to encourage co-operation on nuclear power, was also formed under this treaty. These three branches later merged in 1968 to form the European Communities.

In 1959, Fianna Fail’s Sean Lemass became Taoiseach, and, from the outset, he crusaded for Irish membership of the EEC, believing that it would provide a significant boost to the Irish economy. Ireland first application to join the EEC was submitted in 1961, along with applications from Britain, Denmark and Norway. Doubts were raised over the viability of Ireland’s membership of the European Communities, with concerns that its economy was not sufficiently developed to withstand the potential impact of free trade and competition resulting from EEC membership, and with questions regarding whether Ireland could join if Britain, its main trading partner, did not. There were also concerns regarding Ireland’s neutrality throughout the war, and its non-membership of NATO. In 1962, Lemass addressed these concerns directly in a speech to the European Commission and visited the capitals of the six founding states in order to assure them that the issues raised would not be an obstacle to Irish membership. The EEC Council of Ministers agreed to discuss Ireland’s entry to the EEC in 1962. However, priority was given to Britain and Denmark’s application and Irish negotiations would not begin until the following year.

On the 14th of January 1963, Britain’s application was vetoed by the French President General De Gaulle and all four applications were suspended. Ireland continued to push for membership of the EEC, with Lemass working towards removing trade barriers and improving Ireland’s economy up until his resignation in November 1966, at which point he was succeeded by his Minister for Finance Jack Lynch. On the 11th of May 1967, Britain made a second application to join the EEC, with Ireland’s application following closely behind. However, Britain was again was blocked by President De Gaulle, and, on the 19th of December, Ireland was informed that their application was also rejected.

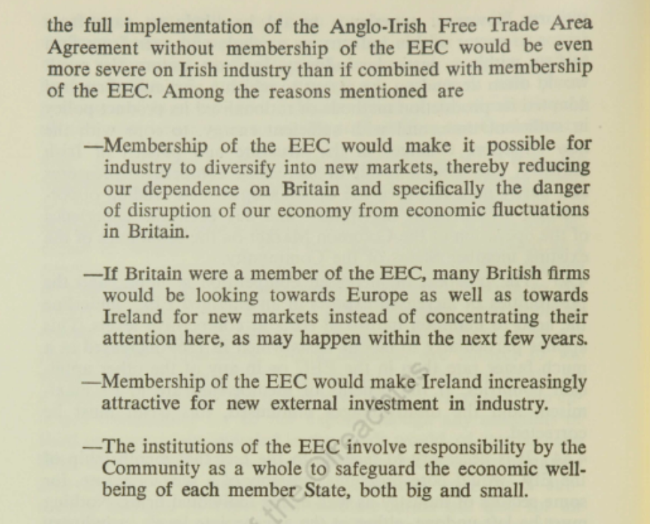

De Gaulle resigned in April 1969, was succeeded by George Pompidou who was more receptive to the accession of Britain and Ireland to the EEC. The June 1969 Irish general election saw Patrick Hillary appointed as Minister for External Affairs, following which he carried out a series of ministerial visits to the European Commission and to the six capitals in order to assure them that Ireland was ready to undertake the political and economic obligations of membership. To support this, a white paper entitled Membership of the European Communities – Implications for Ireland (pictured above) was published in April 1970, outlining the potential effects that acceding to the European Communities could have on Ireland in terms of financial implications, impact on agriculture, fisheries, and industry, movement throughout member states, tax provisions and economic policy, amongst other things. On the 18th of January 1972, the final negotiations took place, and four days later the Treaty of Accession was signed, permitting Irish membership within the European Communities.

Joining the European Communities required a change to Bunreacht na hÉireann, therefore, a referendum was required. The referendum proposed the insertion of a new Article, which stated:

“The State may become a member of the European Coal and Steel Community (established by Treaty signed at Paris on the 18th day of April, 1951), the European Economic Community (established by Treaty signed at Rome on the 25th day of March, 1957) and the European Atomic Energy Community (established by Treaty signed at Rome on the 25th day of March, 1957). No provision of this Constitution invalidates laws enacted, acts done or measures adopted by the State necessitated by the obligations of membership of the Communities or prevents laws enacted, acts done or measures adopted by the Communities, or institutions thereof, from having the force of law in the State”.

The Fianna Fáil government and Fine Gael main opposition united for the purposes of encouraging a Yes vote. However, the Labour party and Sinn Féin were suspicious of the European Communities and the potential impact membership could have on Irish independence, and so, they campaigned for a rejection of the treaty. The referendum was held on the 10th of May, 1972, and resulted in an overwhelming vote for Ireland to join the European Communities, with between 70%-80% of the electorate voting Yes.

The Treaty of Accession came into force on the 1st of January 1973, with Ireland, Britain and Denmark formally joining the European Communities on this day.

From the Documents Laid Collection, DL021475

Anglo-Irish agreement between the government of Ireland and the government of the United Kingdom, Hillsborough, 15 November 1985

1980s

Anglo-Irish agreement between the government of Ireland and the government of the United Kingdom, Hillsborough, 15 November 1985

The late 1960s saw the beginning of a thirty year period of violent conflict in Northern Ireland known as The Troubles, which resulted in the deaths of over 3,500 people and the injury of almost another 50,000.

The Troubles began as a result of both the conflict between nationalist and unionist communities regarding Northern Ireland’s status within the United Kingdom, and the discrimination against the nationalist minority by the unionist majority. In 1964, a civil rights campaign began in Northern Ireland, calling for the end of discrimination against Catholics and Irish nationalists. Although initially peaceful, violence soon erupted between Republican and Loyalist paramilitary groups. The conflict escalated to such a degree that by 1969 British forces were sent to Northern Ireland to intervene, and by 1972, the British government suspended the Northern Ireland Parliament and imposed direct rule from London. An All-Ireland arrangement was considered as the most likely way of resolving the crisis. The first attempt at this was the 1973 Sunningdale Agreement, which provided for both a devolved, power-sharing administration and a role for the Irish government in the internal affairs of Northern Ireland. However, this agreement fell apart in May 1974. A decade later, another attempt was made to bring an end to The Troubles.

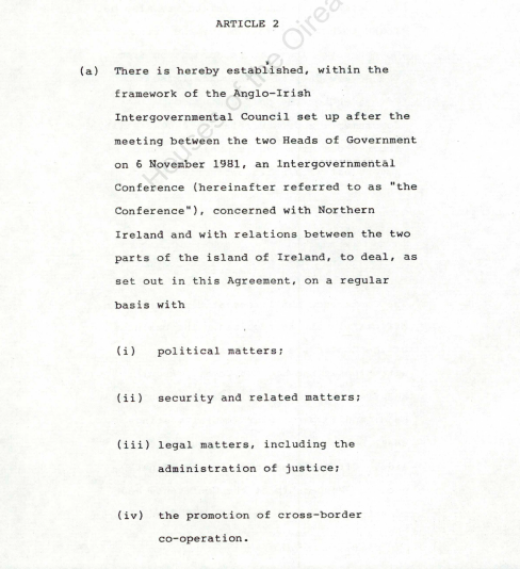

The Anglo-Irish Agreement (pictured above) was an agreement signed on the 15th of November 1985 by Taoiseach Garret FitzGerald and the British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher at Hillsborough Castle in County Down which gave the government of Ireland an advisory role in Northern Ireland’s government. It established the Anglo-Irish Intergovernmental Conference which provided for regular meetings between ministers in the Irish and British governments on matters affecting Northern Ireland, and outlined cooperation in four areas: political matters, security and related issues, legal matters and the administration of justice, and the promotion of cross-border cooperation. It also determined that there would be no change in the constitutional position of Northern Ireland unless a majority of its people agreed to join the Republic and set out the conditions for the establishment of a devolved consensus government in the region.

The agreement was voted through the British House of Commons by a majority of 426, with the majority of the Conservative party, the Labour party and the Liberal-SDP in favour of it. It was also approved by Dáil and Seanad Éireann, despite opposition from Sinn Féin and Fianna Fáil. However, the agreement received severe backlash from several different groups. In the Republic of Ireland, republican dissent stemmed from the Agreement confirming the position of Northern Ireland within the United Kingdom, with assertions that it did harm to Ireland’s claim over Northern Ireland, while for Northern Ireland Republicans, the deal fell short of providing them with a united Ireland. The Anglo-Irish Agreement was also met by fierce opposition by the unionist community of Northern Ireland. Unionist leaders resented being excluded from the negotiations leading to the agreement and were concerned that it would pose a threat for Northern’s Ireland place within the United Kingdom. A campaign of protest was led by the Ulster Unionist Party (UUP) and the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP), including mass protest rallies organised under the campaign heading 'Ulster Says No'. On the 23rd of November 1985, over 100,000 people gathered in Belfast to hear speeches of protest from UUP leader James Molyneuax and DUP leader Ian Paisley. Both unionist parties subsequently resigned their seats in the House of Commons and suspended district council meetings in protest. Thatcher received significant criticism relating to the agreement, with Ian Paisley accusing her of having “prepared Ulster Unionists for sacrifice on the altar of political expediency. They are to be the sacrificial lambs to appease the Dublin wolves”.

The Anglo-Irish agreement was not successful in bringing about an end to the conflict in Northern Ireland, with ongoing attacks by paramilitary groups continuing for many years after. However, it did achieve co-operation between the Irish and British governments – co-operation that is today seen as playing a significant role in the Peace Process through facilitating the creation of the Good Friday Agreement on the 10th of April, 1998. Although there have been occasions of violence since 1998, the Good Friday Agreement is seen by most as the end of The Troubles.

From the Documents Laid Collection, DL045908

The Right to Remarry, a Government Information Paper on the Divorce Referendum, September 1995

1990s

The Right to Remarry, a Government Information Paper on the Divorce Referendum, September 1995

The late twentieth century saw the Irish electorate voting on two referenda relating to divorce. The first divorce referendum was held in 1986 by Garret Fitzgerald’s Fine Gael government, but was rejected by a significant margin, with nearly 65% of the electorate voting against it and only five constituencies voting in favour of divorce, all of which were in Dublin. Western Connacht and Munster constituencies strongly rejected the proposed amendment, in particular, in Cork North West, where 79% of constituents voted “No”.

Lack of clarity regarding possible implications of, and conditions attached to attaining a divorce. In the run-up to the referendum, questions were raised regarding the rights of the divorced couple in relation to property and social welfare. However, despite attempts to clarify the conditions attached to the amendment, the government were unable to address these concerns sufficiently. Anti-divorce campaigners also raised other evils, such as the potential suffering for families, and, in particular, children, as a result of divorce, and the possibility that the easy availability of divorce would open the floodgates and cause a dramatic increase in marriage breakdown in Ireland. Women were particularly targeted by anti-divorce campaigners, with the circulation of pamphlets and flyers advising readers that women would lose succession, pension and property rights, and could even be divorced against their will, should the amendment pass.

Despite the failure of the government to pass the amendment in 1986, the issue of divorce was raised again over the following years. A paper entitled Marital Breakdown: a Review and Proposed Change was published in 1992 by the Department of Justice, declaring the government’s intention to have another referendum on divorce “after a full debate on the complex issues involved and following the enactment of other legislative proposals in the area of family law” (p.9), and, two years later, Irish voters were again asked to vote on the matter when an amendment was introduced by the Fine Gael-Labour government under John Bruton.

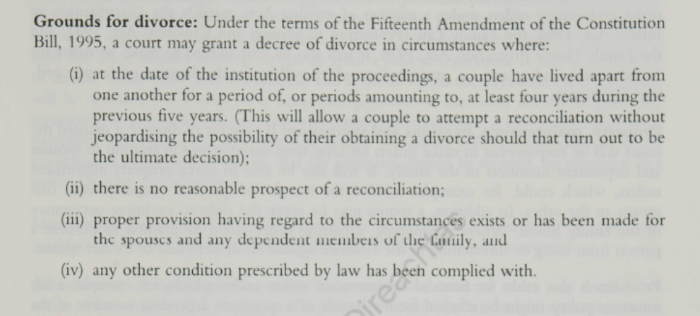

In September 1995, in preparation for the referendum, the Department of Equality and Law Reform published an information guide entitled The Right to Remarry: A Government Information Paper on the Divorce Referendum (pictured above), which provided information relation to procedures involved in the application for a divorce, maintenance payments, impact of divorce on succession rights, property ownership, and social welfare provisions, guardianship and custody of children, tax treatment of married, separated and divorced couples, and other topics of concern raised by the referendum.

The second referendum took place on the 24th of November 1995, and passed by a small margin, with 50.3% of the electorate voting in favour of the amendment and only a little over 9000 votes separating the two sides.

The prohibition of divorce was repealed by the Fifteenth Amendment of the Constitution Act, which was signed into law on the 17th of June 1996. The amendment provided for the alteration of Article 41.3, which provides for the rights of the family. Under the amendment, it now states:

“A Court designated by law may grant a dissolution of marriage where, but only where, it is satisfied that—

at the date of the institution of the proceedings, the spouses have lived apart from one another for a period of, or periods amounting to, at least four years during the previous five years,

there is no reasonable prospect of a reconciliation between the spouses,

such provision as the Court considers proper having regard to the circumstances exists or will be made for the spouses, any children of either or both of them and any other person prescribed by law, and

any further conditions prescribed by law are complied with.”

The Family Law (Divorce) Act was passed in 1996.

From the Documents Laid Collection, DL027551

Diseases of Animals Act 1966 (Foot and Mouth Disease) (Export and Movement Restrictions) Order 2001

2000s

Diseases of Animals Act 1966 (Foot and Mouth Disease) (Export and Movement Restrictions) Order 2001

March 2001 saw an outbreak in Ireland of Foot-and-Mouth Disease (FMD), a highly contagious viral disease that affects cattle, sheep, pig, goats and other cloven hooved animals, following earlier outbreaks in Britain and Northern Ireland. It was the first outbreak of this disease in Ireland since 1941. Strict government policies on the movement of livestock were put in place to deal with the outbreaks, including restrictions on the movement of live animals and animal products throughout the state, and the disinfection of vehicles used for animal transportation.

The outbreak began in the UK, with signs of infection discovered in a group of pigs in Cheale Meats abattoir in Essex on the 19th of February. Following a series of tests, the disease was confirmed as Foot-and-Mouth, and the Minister of Agriculture, Food and Fisheries announced the outbreak the following day. Five mile exclusion zones were immediately placed around the abattoir and the farms that supplied it. The farm next to the abattoir was quickly found to have cases of the disease. The 21st of February saw restrictions placed on the movement of live animals and animal products throughout the UK, with the European Union, Northern Ireland, and the Republic of Ireland also banning the import of live animals and animal and dairy products from the UK. In the days following the announcement, the mass slaughter of infected animals took place in farms around England. However, despite efforts of the British government to limit the spread of the virus, the movement of affected animals prior to, and after, announcement of the outbreak resulted in the spread of the disease to other areas in England, and to Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland. The source of the outbreak was linked to a farm in Northumberland from which the infected pigs found in Cheale Meats abattoir came.

On the 28th of February, a suspected case of Foot-and-Mouth was announced in Northern Ireland amongst sheep imported to a farm in Meigh, south Armagh, from a market in Cumbria. A five mile exclusion zone was set up around the area, but three weeks later the infection had spread to sheep on a farm at Proleek, near Jenkinstown in Co. Louth. An exclusion zone was set up and a cull of healthy livestock around the farm was ordered. Wild animals in the area capable of bearing the disease were also taken down by snipers in order to stop the spread of disease.

Precautionary measures were already in place in Ireland following the outbreak in the UK and increased significantly upon the arrival of the disease in the Republic. Initial restrictions included a ban on imports from the UK of live animals and animal products, an embargo on sales at livestock marts, and controls on the importation of used farm machinery from the UK. On the 28th of February, the Department of Agriculture, Food and Rural Development brought in an additional ban on the movement of susceptible animals within Ireland, other than those going direct for slaughter. A number of precautionary measures, such as controls on access to farms and the introduction of disinfectant mats in areas with a lot of footfall or traffic, were also brought in. Following the outbreak in Louth, Foot-and-Mouth checkpoints were set up on highways and laneways north of Dundalk, with significant disruption to daily life.

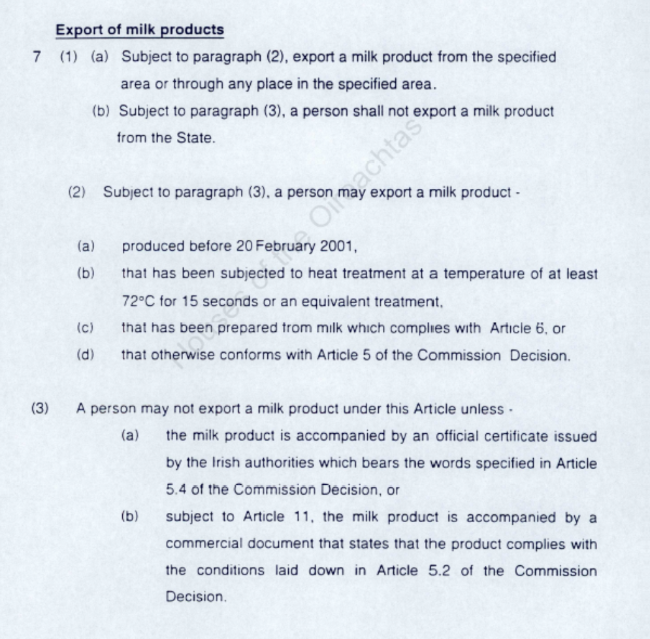

Pictured below is an order dated the 28th of March given by Joe Walsh, Minister for Agriculture, Food and Rural Development, outlining the restrictions to be put in place in order to deal with the Foot-and-Mouth outbreak. Under the order, restrictions were placed on the export and movement of live animals and animal products from, and throughout Ireland and, in particular, Co. Louth.

Exports of animals originating from outside of Ireland were allowed (except where the animal originated in France, the UK or the Netherland, all of which were already affected by the disease) as long as the animal had travelled directly, and without interruption, through Ireland by the main roads or by rail. Additionally, the transported animals were required to bear an appropriate certificate issued by a veterinary inspector and advance notice had to be given by the Department of Agriculture, Food and Rural Development to the relevant authority at the place of destination. Other restrictions laid out by the order included restrictions on the export and movement of fresh and frozen meat, other meat products, milk products, animal semen, ova or embryos, blood products, and hides and skins. In most cases, the items in question were required to have undergone appropriate treatment and preparation in accordance with European Commission Decision No. 2001/234/EC of the 22nd March 2001, and were accompanied by a certificate issued by a veterinary inspector. Some were also required to have been obtained prior to the 20th of February, placed in separate storage, and awarded a health mark.

As with the outbreak in the UK, the European Commission adopted a number of protective measures following the outbreak in Ireland. In a press release released on the 26th of March, 2011, it stated:

“In particular, it will be prohibited:

to move live susceptible animals (bovine, ovine, caprine and porcine species and other bi-ungulates) and their germinal products from Ireland to other Member States and third countries;

to dispatch products, notably fresh meat and meat products, milk and milk products, hides and skins and other animal products from the same species from the county of Louth to other parts of Ireland, to the other Member States and to third countries, unless these products were obtained before 20 February 2001 or have been treated in a way that the risk of spreading the food-and-mouth disease virus is avoided (pasteurisation and heat-treatment of milk, heat treatment of meat products, treatment of skins and hides)

In addition, vehicles used for the transport of livestock and milk have to be disinfected and some restrictions on the movement of horses are put into place. These measures follow the approach already adopted in relation to the outbreaks of FMD in France and the Netherlands.”

Along with the huge constraints placed on the agricultural sector by the restrictions on exporting and moving farming products, the tourism sector in Ireland was also significantly affected by the outbreak, with the cancellation and deferral of a number of sporting and cultural events, including the Wales V Ireland rugby match and St Patrick’s Day celebrations throughout the country. Additionally, tourists were discouraged from visiting Ireland as a result of all the restrictions put in place to deal and the negative publicity surrounding the outbreak.

Over 54,000 animals were culled as a result of the outbreak in Louth, with 250 farmers affected, but, fortunately, the disease did not spread to other areas in Ireland. The disease was mostly contained by May, and, on the 19th of September, Ireland was declared as Foot-and-Mouth free by the World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE).

The UK government gave the all-clear from midnight on the 14th of January 2012, after three months with no new outbreaks. Approximately 10 million animals in total were slaughtered as a result of the outbreak. Smaller outbreaks in Northern Ireland, France and the Netherlands were also successfully contained.

From the Documents Laid Collection, DL028605

Third Report of the Convention on the Constitution, Amending the Constitution to provide for same-sex marriage, 2013

2010s

Third Report of the Convention on the Constitution, Amending the Constitution to provide for same-sex marriage, 2013

One of the most contentious legal and social issues of recent times has been the topic of marriage equality for same-sex couples. The past few years have seen increased awareness of this topic, with various groups within Irish society engaging in animated discussion and debate regarding the legal recognition of same-sex marriages.

In 2010, the Civil Partnership and Certain Rights and Obligations of Cohabitants Act was passed, enabling same-sex couples to enter into civil partnerships and granting them rights similar to those of civil marriage. The Act came into force on the 1st of January 2011 and the first civil partnership ceremonies took place in spring of the same year. Since then, nearly 1500 same-sex couples from every county in Ireland have entered into a civil partnership.

The passing of this Act and the availability of civil partnership for same-sex couples in Ireland marked an important step in the recognition of LGBT relationships. However, with significant disparity in the rights and responsibilities given to civil partners and married couples and with marriage restricted to opposite-sex couples only, there have been calls from marriage equality groups for civil marriage to be further extended to include same-sex couples.

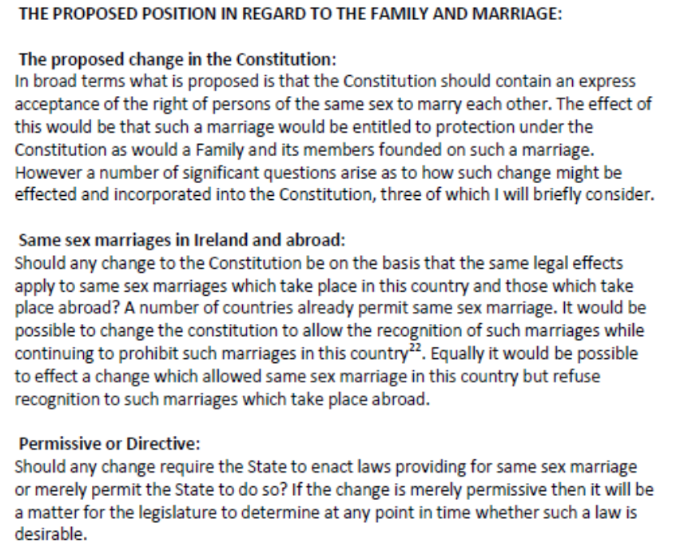

In 2012, the Convention on the Constitution was formed to examine and debate on a number of suggested amendments to the Irish Constitution, including the proposal to introduce same-sex marriage. The Convention was made up of 100 members, including a chairman, 33 members of parliament (29 members of the Oireachtas and 4 members of the Northern Ireland Assembly), and 66 citizens of Ireland. The first plenary meeting was held in January 2013, from which point the Convention were given up to 12 months to complete its work. The third plenary meeting, which focused on the amendment of the Constitution to allow for same-sex marriage, was held from the 13th – 14th of April 2013. This meeting attracted significant public interest, and over one thousand submissions lodged by citizens, advocacy groups and representative organisation were considered as part of the debate. Over the course of the two days, Convention members heard presentations from legal and academic experts and from various advocacy groups, engaged in debates, participated in question and answer sessions, and, in the end, voted on whether the Constitution should be amended. The results of the vote showed that a significant majority favoured amendment of the Constitution, and recommended that the State be obliged to enact laws providing for same-sex marriage as well as laws regarding the parentage, guardianship and upbringing of children within same-sex marriages.

The Convention submitted its formal report for the third plenary meeting (pictured above) to the Oireachtas on the 2nd of July 2013, following which the government had four months to respond to its proposals. In November of the same year, it was announced that a referendum on the legalisation of same-sex marriage would be held in the first half of 2015, with a later statement by Taoiseach Enda Kenny in July 2014 confirming that the referendum would take place sometime in the coming spring. This decision to hold a referendum was welcomed by marriage equality groups, with Kieran Rose, the chairman of the Gay and Lesbian Equality Network (GLEN), describing it as a “historical step”.

From the Documents Laid Collection, DL108218

Last updated: 10 May 2017