On the same day that Dáil Éireann commenced its debate on the Treaty the Parliament of the United Kingdom also convened. Article 18 of the Treaty provided that ‘The instrument shall be submitted forthwith by His Majesty's Government for the approval of Parliament’. This simple phraseology masked a series of significant constitutional and political conundrums.

These arose out of both the substance of the accord and the way it had been negotiated. Not surprisingly, critics of the Treaty in Westminster seized upon these perceived vulnerabilities when the debate began in both the House of Commons and the House of Lords on Wednesday, 14 December 1921.

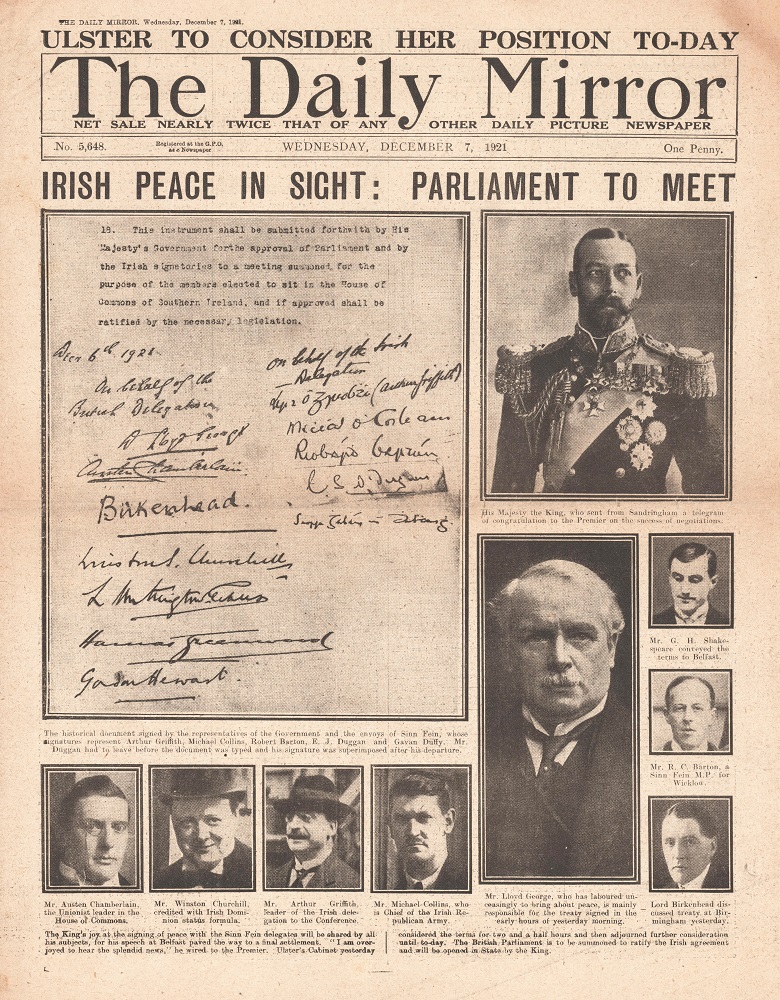

Front page of The Daily Mirror reporting the conclusion of the peace negotiations, December 1921 | ©John Frost Newspapers/Mary Evans Picture Library

The unique nature of the occasion was foreshadowed in the address of the King to the joint meeting of both chambers:

I have summoned you to meet at this unusual time in order that the Articles of Agreement which have been signed by My Ministers and the Irish Delegation may be at once submitted for your approval. No other business will be brought before you in the present Session. It was with heartfelt joy that I learnt of the Agreement reached after negotiations protracted for many months and affecting the welfare not only of Ireland, but of the British and Irish races throughout the world. It is my earnest hope that by the Articles of Agreement now submitted to you the strife of centuries may be ended, and that Ireland, as a free partner in the Commonwealth of Nations forming the British Empire, will secure the fulfilment of her national ideals. I pray that the blessing of Almighty God may rest upon your labours.

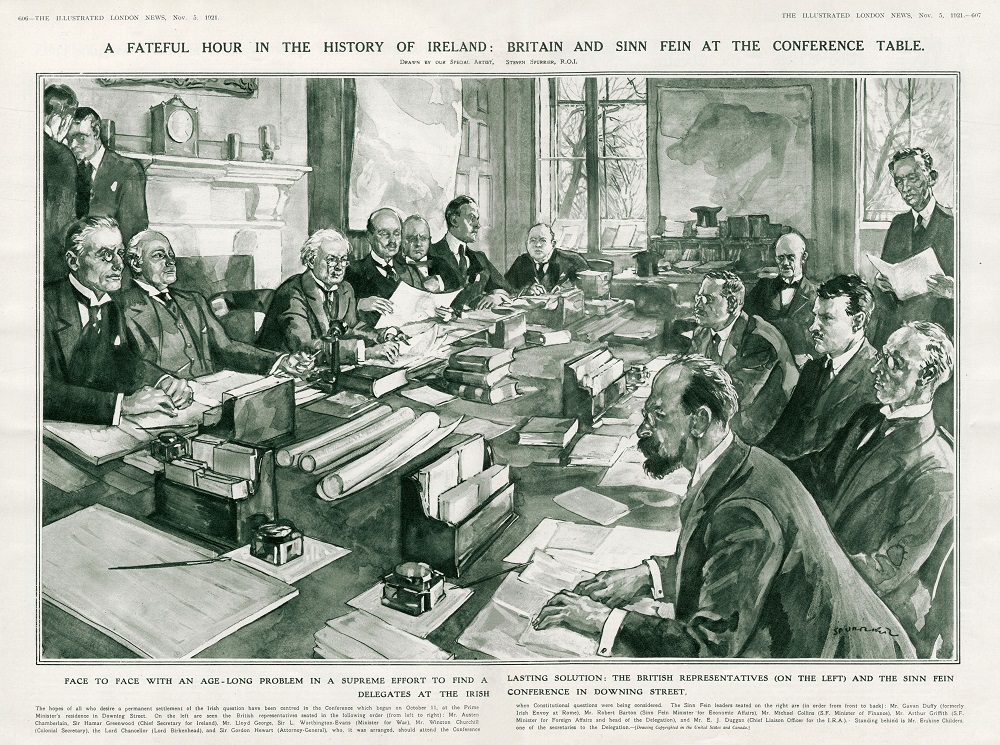

The Treaty negotiations at 10 Downing Street as represented in The Illustrated London News of 5 November 1921 | © Illustrated London News Ltd/Mary Evans Picture Library

What followed was three days of at times vitriolic debate. Opponents of the Treaty moved amendments in the Commons and the Lords. The Government ultimately defeated these amendments with crushing majorities in the division lobbies and the original—laudatory—wording of the address was endorsed intact. Its opponents, however, landed telling blows during the exchanges. These came from Ulster Unionist MPs and from within the ranks of the Conservative Party and were directed against a Tory-dominated coalition Government. This endowed both the debate and the vote with signal political, and at times personal, resonance. The virtual monopoly of power at Westminster enjoyed by the House of Commons meant its discussions were the more important, but the personal exchanges were at their most pointed in the House of Lords.

Parallel debates

The debate on the Treaty in Westminster occurred simultaneously with that in the Dáil and one of the most striking features of the deliberations is the ‘real time’ connection between the two. There was a wire service between Dublin and London and some newspapers published successive editions over the course of a day. This meant that speakers in Westminster were aware of contributions made in the Dáil, and vice versa, sometimes only a few hours after the original speech (notwithstanding the fact that the initial Dáil sessions were held in private).

Speakers in Westminster were aware of contributions made in the Dáil, and vice versa, sometimes only a few hours after the original speech.

During the course of his speech Lt. Col. Martin Archer-Shee (half-brother of the famous ‘Winslow Boy’, George Archer-Shee, and one who voted against the Government) spoke thus of the Irish exchanges:

‘I see that already Michael Collins—it is on the tape—said that one of the Sinn Feiners had called him a traitor, and that was just before they adjourned for lunch.’

Rupert Gwynne, likewise, paraphrasing the famous image invoked by Collins, observed that the Treaty ‘is accepted by the Sinn Feiners only as an instalment of their claim for a Republic. It is a “milestone” as it has been expressed by one of their own representatives.’ In the same vein Colonel John Gretton, when speaking of the standing of the Irish representatives, observed that those ‘who came over to discuss these articles were the delegates of the Irish Republic. I gather from the statement made by Mr. De Valera at the meeting in Dublin yesterday, that the document stated so.’

Michael Collins arriving at Earlsfort Terrace for the Treaty Debates | Courtesy of the National Library of Ireland

Other critics, such as Ronald McNeill, followed a slightly different track, suggesting that proceedings in London should be halted pending the outcome of the decision in Dublin. At this point it seems the belief was widespread that the debate in the Dáil—a much smaller body than either the House of Commons or Lords—would be relatively brief. The contrary point of view was put forward by Arthur Henderson, Chief Whip of the Labour Party and supporter of the Treaty, who argued that the hand of the pro-Treaty side in Dublin would be greatly strengthened by an early, supportive declaration from Westminster.

Other supporters of the accord were likewise aware of the sensitivities in Dublin and sought to steer the Westminster debate clear of the rocks of partisanship. Sir Samuel Hoare, the first to speak in support of the Treaty in the Commons debate, noted that:

‘The wreckers of Dublin are attacking the peace. Let us in this House not make more difficult the task of men of good will.’

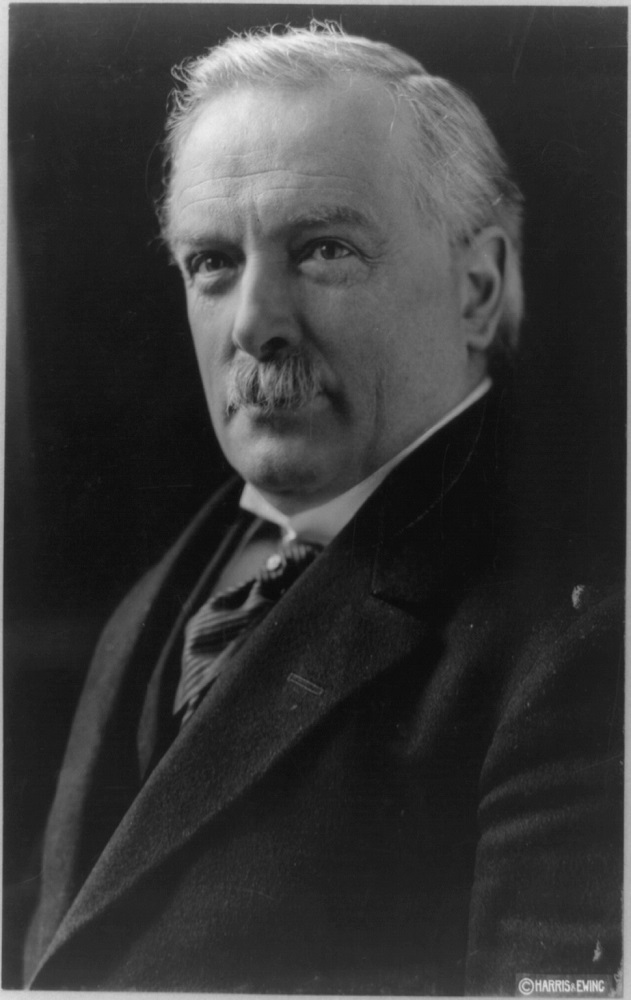

The leader of the Labour Party, John Clynes, spoke similarly, but the most telling contribution on this point came from the Prime Minister, David Lloyd George. During the early exchanges the Prime Minister said that the debate in London ‘must necessarily be hampered’ by the knowledge that their words were being reported and used against the Treaty in Dublin. While praising the actions of Conservative politicians, such as Lord Birkenhead, who had taken a huge political risk in signing the agreement, he noted that similar, if not greater, risks had been taken by the Irish signatories. He said:

‘The risks they took are only becoming too manifest in the conflict which is raging at this hour in Ireland, and all honour to them. Not a word will I say—and I appeal to every Member in this House not to say a word—to make their task more difficult.’

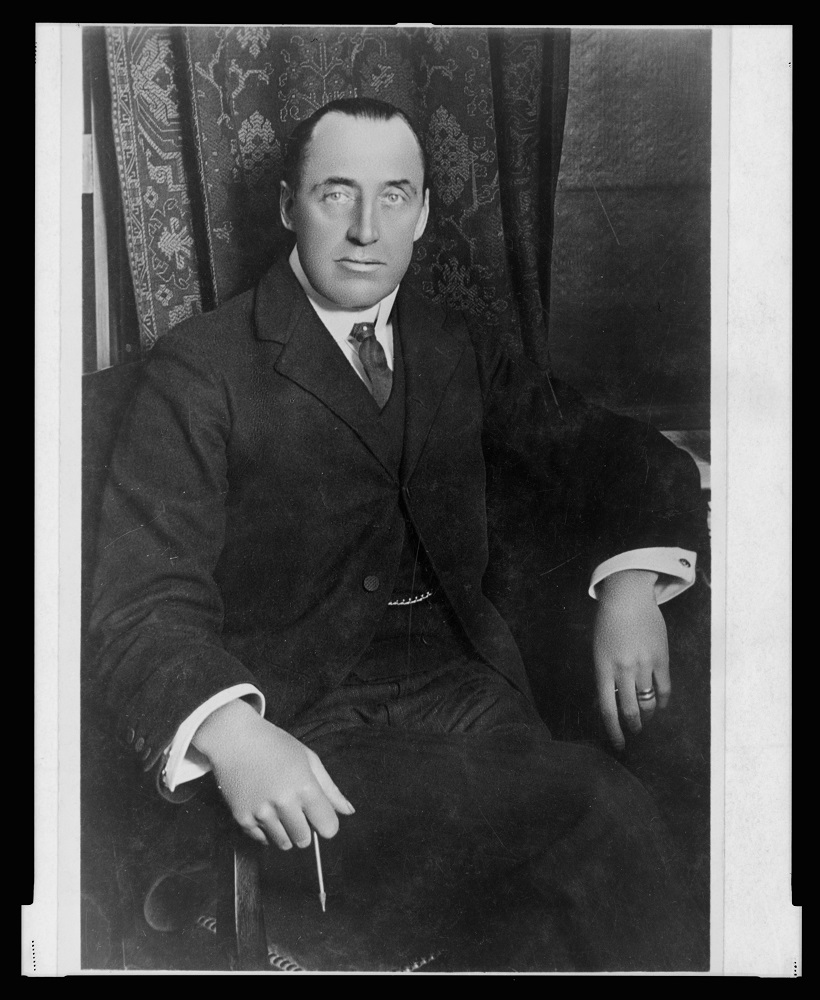

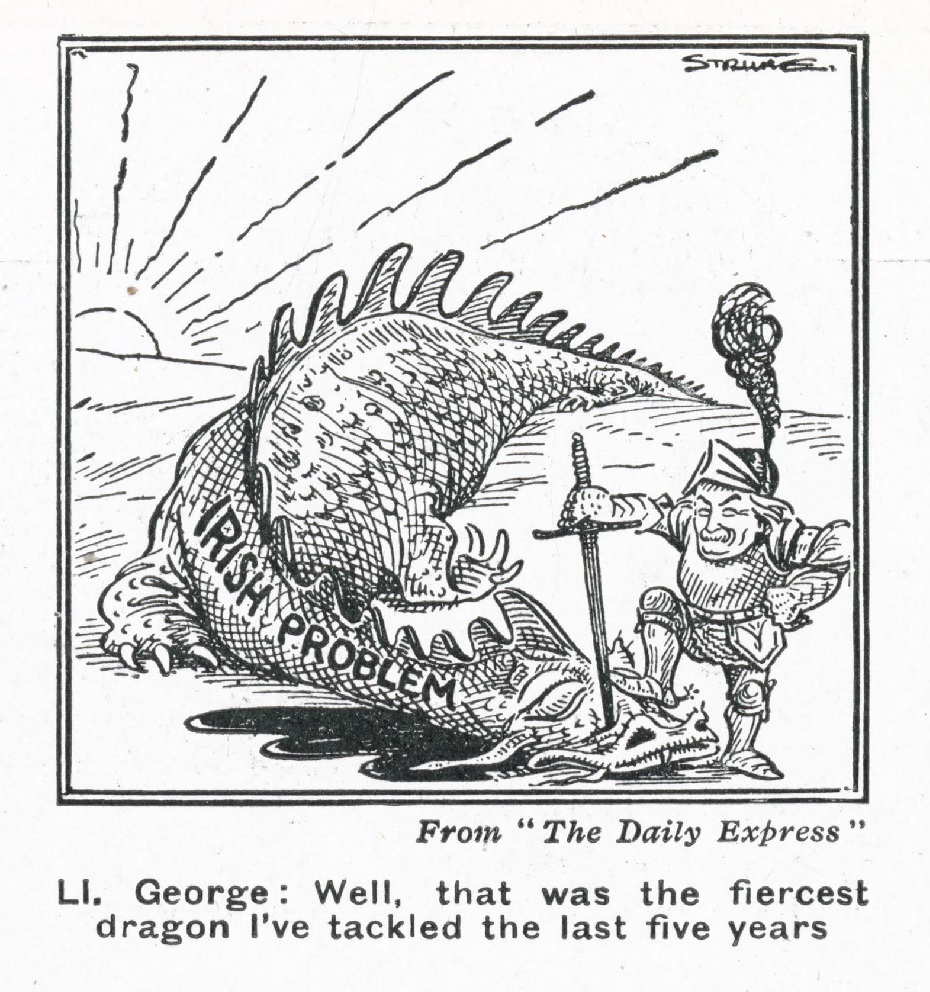

David Lloyd George, Prime Minister of United Kingdom (1916 - 1922) | Courtesy of the Library of Congress

Constitutional revolution

The die-hard critics of the Treaty were, of course, not in the mood to heed this request and brought other arguments to bear against its endorsement. One was that the motion—which in their eyes recognised the secession of a part of the United Kingdom—proposed the greatest change in the ‘British’ state since the creation of the United Kingdom under the terms of the Irish Act of Union 120 years previously. Yet, they complained, the Government would not countenance any amendments to the text agreed with the Irish representatives. Instead, the Government had merely promised that the consequent legislation that would provide a statutory foundation for the creation of the Irish Free State could be debated and amended in the normal fashion. The critics argued that such a procedure amounted to a constitutional revolution, one that compounded the Government’s capitulation to rebellion in the form of the truce with the republican forces during the preceding summer.

Lloyd George’s riposte was well made, reminding such critics that the history of Britain was marked by a series of compromises with rebels and that Parliament ‘was the last authority in the world’ to maintain the proposition that rebellion should be ruthlessly crushed, given that it owed ‘its rights and privileges to concessions made to successful rebels’. The implied reference to the civil war of the 17th century would not have been lost on those who had endorsed the Ulster unionist extra-parliamentary resistance to the third Home Rule bill 7 years before.

Northern Ireland

The provisions of the Treaty in respect of Northern Ireland came in for special attention from its opponents. The position of Ulster Unionists was that in accepting the Government of Ireland Act the previous year they, loyalists all, had gone to the ultimate limit of the concessions they would or could make as part of their contribution to an Irish settlement. They had been assured that nothing further would be demanded from them. Yet now, they argued, the same Government had altered its position in three fundamental ways, all in the interests of seeking an accommodation with avowed rebels: the initial inclusion of Northern Ireland within the jurisdiction of the Irish Free State; the establishment of a Boundary Commission to redraw the border should Northern Ireland opt to vote itself out of that jurisdiction; and the perception that economic pressure would be applied to force Northern Ireland to accept reunification.

Charles Craig, brother of the Prime Minister of Northern Ireland, addressed the first point. He noted that Northern Ireland would have to incur the odium of voting itself out of the jurisdiction of the Free State. This would mean voluntarily cutting off those unionists in the other three counties of Ulster and across the south and west of the island. He and other likeminded speakers made it clear they would indeed take that route but bitterly complained that the responsibility for the separation would be seen to be theirs.

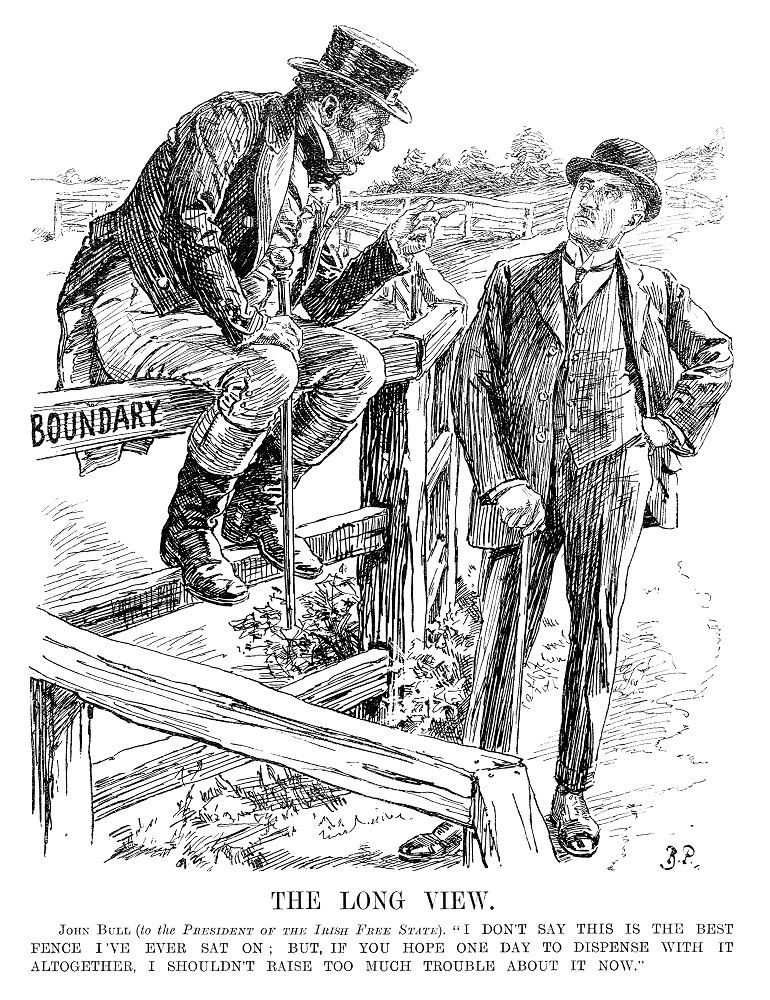

Cartoon published on the inaugural meeting of the Irish Boundary Commission in 1924 | Punch Cartoon Library/TopFoto

The establishment of the Boundary Commission, which threatened to transfer population and territory from Northern Ireland to the Free State, compounded this situation. It would mean the loss of still more unionists to Dublin control. While contradictory signals were sent by supporters of the Government’s position as to just how extensive this transfer might be, William Coote summed up the feelings of those hostile to the Treaty:

‘The ink is hardly dry on the signature of the King [on the Government of Ireland Act] when we are informed that there is to be a fresh delimitation of those boundaries.’

He also repudiated the idea that the promise of lower taxes in the Irish Free State would be sufficient to overcome unionist objection to unification.

The Government’s main defence against such charges was that Northern Ireland’s consent was necessary for such unification to take place, though the Prime Minister made it clear that a united Ireland was London’s preferred option. Austen Chamberlain, in his summation of the debate for the Government prior to the division in the Commons on the third and final day, gave this line an added twist, astutely noting that:

‘Hon. Members suggest that we had no right to invite Ulster to consider whether she could not come into an All-Ireland Parliament. If we had not put that proposition to them, we should never have got what we have got for the first time—the assent of the representatives of Southern Ireland to recognise the right of Northern Ireland to remain outside.’

The House of Lords

Many other issues had been thrown into the debate in the lower house—the novel wording of the oath, the impact of the agreement on the Empire and Britain’s standing in the world at large, the position of loyalists in the Free State, and Britain’s defence arrangements, to name but four. Not surprisingly, the debate in the House of Lords followed strikingly similar lines with virtually identical language to that employed in ‘the Other Place’.

What gave the debate in the upper house added bite, however, was the presence on opposing sides of the aisle of two of the highest profile members of the Unionist–Conservative alliance against the third Home Rule Bill. These were Edward, now Baron, Carson and F.E. ‘Galloper’ Smith, now Lord Birkenhead and Lord Chancellor. The very closeness of their earlier alliance and friendship rendered this public parting of the ways all the more memorable and all the less pleasant.

Sir Edward Carson | Courtesy of the Library of Congress

Carson made his maiden speech during the debate and was unstinting in the venom he directed towards the agreement. He believed it marked the death of the Conservative party and sanctioned the desertion of southern loyalists from whose ranks he, of course, sprang. It was the formal recognition of military defeat at the hands of the republican ‘murder gang’, an unprecedented ‘outrage upon constitutional liberty’, and the beginning of the end of Empire. It was the culmination of a series of betrayals of the Union by the Government in London that had begun with the passage of the 1914 Home Rule Act, continued with the failure to apply conscription to Ireland, and culminated in the enactment of the Government of Ireland Act. Carson’s was the speech of a man who realised that the cause he had championed had been defeated as a result of a volte-face by some of its most passionate erstwhile allies and he deployed his full rhetorical arsenal to damn their change of heart.

Carson’s was the speech of a man who realised that the cause he had championed had been defeated as a result of a volte-face by some of its most passionate erstwhile allies and he deployed his full rhetorical arsenal to damn their change of heart.

As the Government spokesman in the Lords it fell to Birkenhead to respond to these and other criticisms while wrapping up the debate. True to form he met linguistic fire with fire, dismissing opponents of the Treaty as ‘medievalists’ who failed to recognise the monumental changes wrought in statecraft by the Great War. He was especially contemptuous of Carson’s allegation that he (Birkenhead) had attached himself to the Ulster cause solely as a means of self-promotion. While accepting, perhaps surprisingly, that the Treaty represented ‘a military humiliation’, he dismissed the alternative of intensified repression proposed by the die-hards on the basis that it would merely produce ‘memories a thousand times more bitterly inflamed’, while the core issues would remain to be negotiated at the end of hostilities. It was the speech of a man who realised the cause he had championed had run its course and he was determined to ensure he would not be found on the losing side of history.

The Treaty was almost instantly forgotten in British political consciousness and the Irish Question disappeared from the Westminster agenda | © Illustrated London News Ltd/Mary Evans Picture Library

There were, thus, significant differences and parallels between the ratification debates in Dublin and London. The most striking difference between them is what happened after they were concluded. The Treaty was almost instantly forgotten in British political consciousness. The ‘Irish Question’, which had occupied so much time and energy over the previous 120 years, disappeared from the Westminster agenda for nearly 50 years. In Ireland, however, the division of opinion regarding the Treaty, and the ensuing Civil War, poisoned the well of Irish politics for many decades and arguably still casts a shadow over the modern political scene.

Full text of the debates in Westminster

To read the full text of the UK Parliament's debates on the Treaty, visit the Hansard website.